Part III: The Cast of Unova

Part III of our tribute to Pokémon Black and White focuses on each of the games’ many characters.

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Hilda and Hilbert | Juniper | Bianca | Cheren | The Gym Leaders | The Elite Four | Alder

Team Plasma Grunts | Concordia and Anthea | The Seven Sages | The Shadow Triad | Ghetsis | N

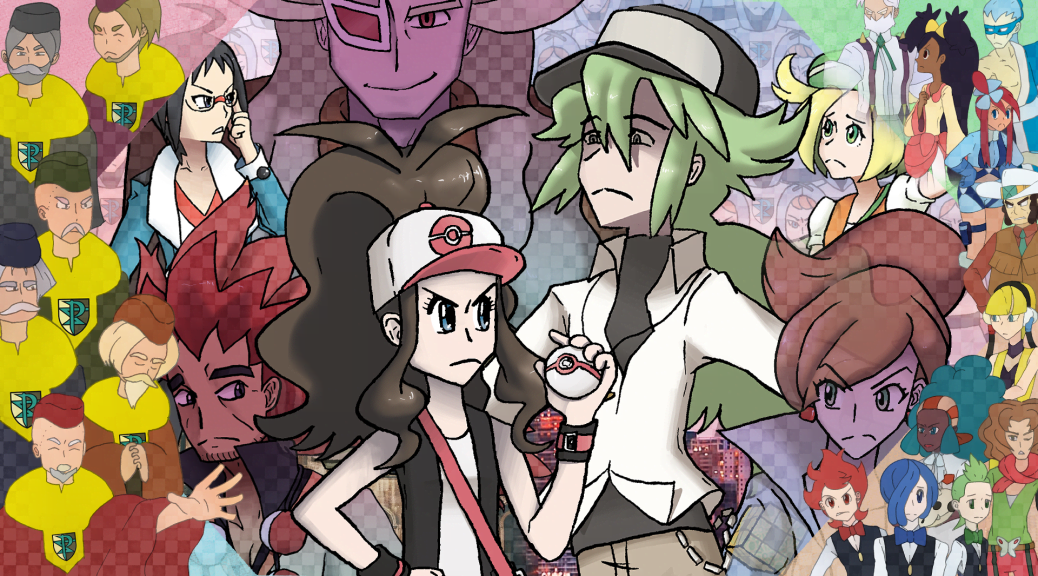

Team Plasma Grunts

The visual imagery of Team Plasma is deeply rooted in effective symbolism befitting the complexity of Black and White. Plasma itself is a state of matter—alongside solid, liquid, and gas—in which gas becomes so hot that its particles’ electrons rip away, changing the gas’s charge from neutral. It may seem elusive, but most of the observable universe is made up of plasma, including the stars and sun. Even lightning,1 like Zekrom’s Bolt Strike, and fire of high enough temperature,2 like Reshiram’s Blue Flare, are in the state of plasma.

The ionization of molecules—the separation of the electrons from the rest of the ion—can be seen as analogous to Team Plasma trying to separate people from humans. But plasma itself is so highly conductive that distant electromagnetic fields—and magnets in general—control the plasma’s behavior more than the plasma does itself.3 This even more clearly aligns with the goals of Ghetsis, who would be able to freely control the populace once people and Pokémon have been separated.

Team Plasma’s visual imagery is also highly befitting of Black and White’s theme of separation or dichotomy. The most obvious can be seen in the team logo, a shield shape that’s half white and half black. The letter “P” splits the logo down the middle, colored blue and shaped like a sword, specifically a rapier. A stylized, pointed letter “S” runs behind it—in game, the “S” is animated, sharply moving from right to left like a bolt of lightning. The color blue is special because, as the color of the sky, it has many special symbolic meanings. Blue is generally seen as “good,”4 with the sky’s infinite expanse and direct association with the heavens making it a color of spirit, intellect, and reflection,5 indicating the consideration and reflection one must do to realize their way of life may, in fact, be harmful. Blue is also the color representing truth, faith, and devotion,6 reflecting the complete devotion and faith Team Plasma have in their cause, believing it to be the one and only truth. Blue also represents purity,7 as in Team Plasma’s purity of motive: some members genuinely believe separating people from Pokémon is for the benefit of Pokémon, and N especially falls into this category.

Team Plasma’s visual imagery is also highly befitting of Black and White’s theme of separation or dichotomy. The most obvious can be seen in the team logo, a shield shape that’s half white and half black. The letter “P” splits the logo down the middle, colored blue and shaped like a sword, specifically a rapier. A stylized, pointed letter “S” runs behind it—in game, the “S” is animated, sharply moving from right to left like a bolt of lightning. The color blue is special because, as the color of the sky, it has many special symbolic meanings. Blue is generally seen as “good,”4 with the sky’s infinite expanse and direct association with the heavens making it a color of spirit, intellect, and reflection,5 indicating the consideration and reflection one must do to realize their way of life may, in fact, be harmful. Blue is also the color representing truth, faith, and devotion,6 reflecting the complete devotion and faith Team Plasma have in their cause, believing it to be the one and only truth. Blue also represents purity,7 as in Team Plasma’s purity of motive: some members genuinely believe separating people from Pokémon is for the benefit of Pokémon, and N especially falls into this category.

The logo’s letter “P” taking on the appearance of a sword further ties into Team Plasma’s visual design. The grunts are dressed as knights, who were, in the Middle Ages, “professional soldiers in the employ of individual kings.”8 The team’s unique uniform isn’t an oddity but rather an intentional thematic choice, tying together the king of Team Plasma, N, and his knights, whose base of operation is a castle.

Within the grunts’ uniform we see even more clever design choices. The majority of their outfit comprises of light colors, with light blue gloves and boots and a light blue hood covered by a white surcoat. Although each culture is different, light colors, especially white, are seen in western tradition specifically as positive compared to darker colors such as black.9 Similar to blue, white tends to symbolize grand ideas such as purity, truth,10 innocence, and sacredness or divinity.11 Even more than that, white represents striving for perfection that has been lost: in religious belief, returning to the perfect state of Eden;12 for Team Plasma, returning Pokémon to their perfect state that they once held before humans enslaved them.

Within the grunts’ uniform we see even more clever design choices. The majority of their outfit comprises of light colors, with light blue gloves and boots and a light blue hood covered by a white surcoat. Although each culture is different, light colors, especially white, are seen in western tradition specifically as positive compared to darker colors such as black.9 Similar to blue, white tends to symbolize grand ideas such as purity, truth,10 innocence, and sacredness or divinity.11 Even more than that, white represents striving for perfection that has been lost: in religious belief, returning to the perfect state of Eden;12 for Team Plasma, returning Pokémon to their perfect state that they once held before humans enslaved them.

But underneath their holier-than-thou light colors that reinforce the conviction they have in their beliefs is a dark, almost black, bodysuit covering all but their faces. Unlike the innocence of white, black tends to represent ignorance,13 the lack of information and alternate perspectives that lead to bigotry. Their own mantra, as stated in the Pinwheel Forest, includes “We are in the right!” and “Everyone else is wrong!”

Black can also simply represent “darkness, negative forces,” or just plain “evil” compared to the more positive interpretations of white,14 accurately encompassing the duplicitous nature of Team Plasma as a whole. Even their “white knight” facade in general ties into this cleverly: traditional depictions of “Black Knights” and “White Knights” similarly fall into tropes of “badness” and “goodness” respectively, but white knights traditionally also conquer15—something that, nowadays, isn’t seen as particularly positive.

Which is why we return to the sword emblazoned on the Team Plasma logo. In Medieval times, people were knighted with the tip of a sword,16 and knights would be expected to engage in battle. The grunts of Team Plasma are N’s knights, fighting for him as a part of their war to free Pokémon. Swords themselves are very aggressive symbols, representing strength or power in all cultures. Their supposed ability to cut apart good and evil17 isn’t only indicative of Team Plasma’s belief in their righteousness, but another similarity to their goal of splitting apart people and Pokémon.

The sword also symbolizes war,18 and while Team Plasma has been compared to other hypocritical extremist organizations such as the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA)—who, despite their name, operate an animal shelter that kills thousands of animals per year19—there’s a far more apt comparison to be made. The blatant knighthood imagery directly references the Crusades.

“We are in the right!”

“Everyone else is wrong!”

“If you don’t think the same way we think, we’ll use all our power to eliminate you!”

The Crusades were wars initiated by various Christian popes to conquer land then owned by Muslims. It’s not a stretch to point out the similarities between Team Plasma’s methods and that of a bloody, ruthless series of wars perpetrated by a supposedly peaceful religion against people whose beliefs are different yet still built upon their own.

Team Plasma’s absolute beliefs justify their actions in their minds. As one grunt explains to you in Wellspring Cave, they “have right on [their] side,” and you and Cheren simply “fail to understand” what they’re trying to do. And after their theft of the Dragon Skull at the Nacrene Museum, a little girl ponders, “Those thugs sure were bold… It’s almost as if they believe they are doing the right thing.” The rallying cry of the very first crusade was “Deus vult”—the crusaders felt they were just in instigating war because “God wills it,”20 just as Team Plasma believes they’re doing what’s right, either for the sake of Pokémon, or for their own benefits.

By now we’ve seen precisely why Team Plasma members behave as they do: they’re a blatant reference to the hypocritical masses, how people will justify cruelty in the name of “justness.” There’s no shortage of “real-life Team Plasmas” in this world—from the aforementioned PETA and crusaders, to those who claim to be “pro-life” but support the death penalty, and even to law enforcement groups who don’t fairly enforce the law. Both the “good” and “bad” sides of Team Plasma believe what they’re doing is “right,” and it’s not outlandish that they both exist within the same organization. And like the very crusaders they’re based upon, Team Plasma can get away with certain criminal actions such as Pokémon theft without the populace at large attributing it to a corrupted core, instead incorrectly viewing it as a few rotten apples souring an otherwise fruitful tree. But this brings us to another typical point of contention against Team Plasma: that is, no matter how believable it is for the “bad” side of Team Plasma to want the complete subjugation of Unova, the “good” side is completely unreasonable for wanting to separate people and Pokémon to begin with.

“No reasonable person would ever, ever think that Pokémon don’t enjoy being used by Trainers to battle,” you may be thinking. “The part of Team Plasma that thinks that Pokémon should be liberated are a bunch of idiots who don’t make sense! And there’s no way anyone listening to them would believe what they say, either!”

Let me introduce you to Buizel and Ambipom.

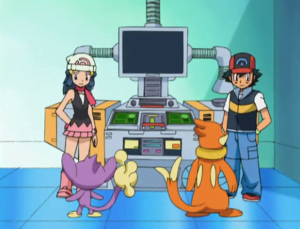

Every non-mainline piece of Pokémon media showcases how Pokémon are all individuals. In the anime, Ash and Dawn trade their Pokémon with each other because their interests don’t align. Ash wants to focus on battling, but his Aipom doesn’t, while Dawn’s Buizel would rather be battling than participating in Contests. Under the ownership of their new Trainers, Aipom evolves into Ambipom and has a blast participating in Contests with Dawn, and Ash and Buizel challenge some of Sinnoh’s Gym Leaders together.

Every non-mainline piece of Pokémon media showcases how Pokémon are all individuals. In the anime, Ash and Dawn trade their Pokémon with each other because their interests don’t align. Ash wants to focus on battling, but his Aipom doesn’t, while Dawn’s Buizel would rather be battling than participating in Contests. Under the ownership of their new Trainers, Aipom evolves into Ambipom and has a blast participating in Contests with Dawn, and Ash and Buizel challenge some of Sinnoh’s Gym Leaders together.

But it isn’t just the anime that reinforces such ideas. The Mystery Dungeon crossover series centers entirely around Pokémon as individuals. The Detective Pikachu live-action movie is set in a world almost exactly as N would have it: although people and Pokémon aren’t separated, the use of Poké Balls and battling is illegal. As such, Pokémon have occupations similar to humans such as the crossing guard Machamp.

And even the main series video games showcase this to some extent. Generic NPCs and sometimes more notable characters who don’t engage in battle will note that their Pokémon don’t always want to battle, either. In Gold, Silver, and Crystal, Machoke can be found leveling the ground in Vermilion City. In Omega Ruby and Alpha Sapphire, Lisia’s rival Chaz has a Machoke who enjoys Contests. It’s as each professor says when they introduce the player to the world of Pokémon: sometimes we battle with Pokémon, but not all the time. Sometimes we work together to accomplish certain tasks, or to simply treat Pokémon as pets.

It’s only with the player’s Pokémon that this individualism doesn’t come through, and rightfully so. It’s impossible to incorporate narratively, and to force it mechanically would make an already complex system more convoluted. Imagine if you wanted to catch a new member of your team, but a newly-added mechanic turns up against your favor—this Pokémon you caught “prefers Contests,” so its attacks in battle will be weaker and its friendship value will go down rather than up as you fight. The reason why mechanics such as friendship exist is because battles are a necessity to complete the game. High friendship is a reward for doing well in battle, and lower friendship is the penalty for doing poorly. It doesn’t exist to instill the idea that all Pokémon love to engage in combat but rather to add more layers to the primary gameplay. But what benefit would a “likes or dislikes battling” stat have when battling is a requirement to complete the game? To force players to recognize that each Pokémon is an individual with individual interests because they won’t imagine it themselves?

The reality is, players already do this themselves. Pokémon is a role-playing game, and your role isn’t only that of the player character—it’s also your party of Pokémon. See any fanmade “Nuzlocke” comic to get a sense of just how much creativity and imagination goes into the mind of a player fleshing out their team, applying personality traits, interests, goals, dreams, and even backstory to what is otherwise a set of 0s and 1s within a game cartridge.

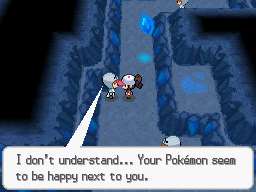

To the NPCs who exist in these game cartridges and watch Ghetsis’s speeches in confusion, and perhaps even a tinge of fear, what Team Plasma says has merit. These characters don’t see Pokémon as party members used to reach the end of a video game. They themselves aren’t heroes who earn each and every badge and save the universe and claim the title of Champion as the player does. They, who could never hope to catch a legendary Pokémon themselves, see N beside the legendary dragon and think he must have a point. They recognize that maybe, just maybe, Pokémon can have unique interests and are hurt by being forced into specific roles—and especially battle—by the people who own them. And unless they can understand what Pokémon say or think, how can they know that they’re doing what their Pokémon wants? How can they be sure that their own Pokémon is staying by their side because they want to, rather than out of obligation or fear, or because they’re controlled by their Poké Ball? Pokémon won’t join your team without being caught first, after all.

Another major issue Team Plasma faces is the consistently near-utopian state of the Pokémon world. It’s so idealized that it runs on the assumption that you, the player, would never do anything bad. Really, the worst thing a player could possibly do is not leave a tip in X and Y. When you win against another Trainer, you take prize money, but not their Pokémon. Most people in the Pokémon world are like this… except for obvious “bad guys” like Team Plasma. A Trainer in Driftveil tells you that “Those Team Plasma meanies forced me to battle them. And when I lost, they stole my Pokémon!” While this is entirely unforgivable, it forces you to wonder about the legitimacy of N’s—and the “good side” of Team Plasma’s—goals. In the world of Pokémon, when two Trainers’ eyes meet, they must battle—and no, there is no running from a Trainer battle. What will stop other people, good or bad, from doing the same thing—forcing a battle and stealing the loser’s Pokémon?

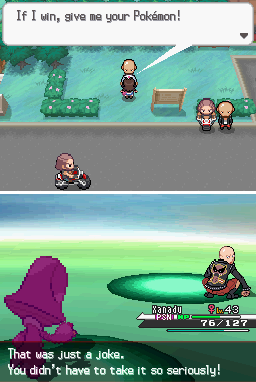

This is even brought up on Route 9, where a Roughneck insists that if you lose to him, you give him your Pokémon. You can’t “canonically” lose any battle, however, leading him to brush it off as a joke. The rules, the formulas, of the Pokémon world are set up in a way that allows people to do bad things with relative ease. The only reason why they don’t is because, conveniently, all the bad people of any given region happen to congregate into a single organization. We assume that our Pokémon enjoy what we make them do because the idealized nature of the Pokémon world holds back potential conflict in the series. Only the evil team can do any harm, so the Pokémon we see outside of their control must be perfectly content with their station in life, right? But by holding back the kinds of conflict that can occur, the series narratives are similarly restricted.

The Pokémon series was not established with nuance. Things that need to exist for the sake of gameplay, such as Gyms and Gym Leaders, simply exist with no explanations as to how or why and with no one at all thinking to question them. In the same way, the pretense that catching, battling, and even trading away Pokémon is ethically sound is an unquestioned given in the Pokémon series. We question things we’re uncertain about, or things we perceive to be wrong and must change. The steadfast nature of the Pokémon world implies its absolute perfection, resulting in narrative conflicts that will always feel slightly contrived in some way or another, because it’s absurd to do evil in an otherwise unquestionably perfect world.

The Pokémon series was not established with nuance. Things that need to exist for the sake of gameplay, such as Gyms and Gym Leaders, simply exist with no explanations as to how or why and with no one at all thinking to question them. In the same way, the pretense that catching, battling, and even trading away Pokémon is ethically sound is an unquestioned given in the Pokémon series. We question things we’re uncertain about, or things we perceive to be wrong and must change. The steadfast nature of the Pokémon world implies its absolute perfection, resulting in narrative conflicts that will always feel slightly contrived in some way or another, because it’s absurd to do evil in an otherwise unquestionably perfect world.

Black and White replicate the formulaic nature of the Pokémon series while incorporating it as an actual narrative, and one of the easiest ways to do that is by questioning it. Team Plasma’s goal for Pokémon liberation draws attention to the typically unquestioned nature of the Pokémon series and welcomes the player to ponder it, too. It’s not outlandish to point out that evil does exist even within the world of Pokémon, and it exists both within and outside of the confines of the games’ evil teams, providing merit to Team Plasma’s central idea of Pokémon liberation.

What stops their goal from being valid enough to warrant reaching fruition isn’t that Pokémon always love fighting each other until one of them loses consciousness. Rather, it loses its validity with the way it directly goes against the very fundamentals holding up the series. The main reason why Team Plasma can’t succeed is because people and Pokémon need to be together for the Pokémon series to continue. This genius narrative decision allows Team Plasma to have a goal that is simultaneously nuanced yet intrinsically “wrong.” This delightfully dichotomous contradiction justifies their defeat, a necessary component of the Pokémon series’s current confines in which a blatantly “good” player must always, without fail, triumph over all adversaries.

In the world of Pokémon, the only way you can triumph over your adversaries is by besting them in battle, leading to the final issue people tend to take with Team Plasma: their methods. The problem isn’t that they use force, because that’s clearly part of their intentional hypocrisy, just as the crusaders started wars despite knowing wars are unethical. Rather, it’s how Team Plasma uses force that’s scrutinized: they claim Pokémon shouldn’t be used in battle, but they battle regardless.

This should be proof enough of Team Plasma’s duplicity, making them poor villains that anyone would be foolish to trust, right? Not quite. In reality, Team Plasma has no choice in the matter: battling is something they have to do. Think about how Team Rocket, the literal Poké-Mafia, could be shut down by a 10-year-old beating its boss in a battle. “Winning makes you right” is heavily ingrained into the Pokémon series formula. Team Plasma has no choice but to use the rules that govern this world before they can change them. It’s for this very reason that N himself battles, and to offset it, he releases his Pokémon back into the wild after every battle to ensure they fight as little as possible.

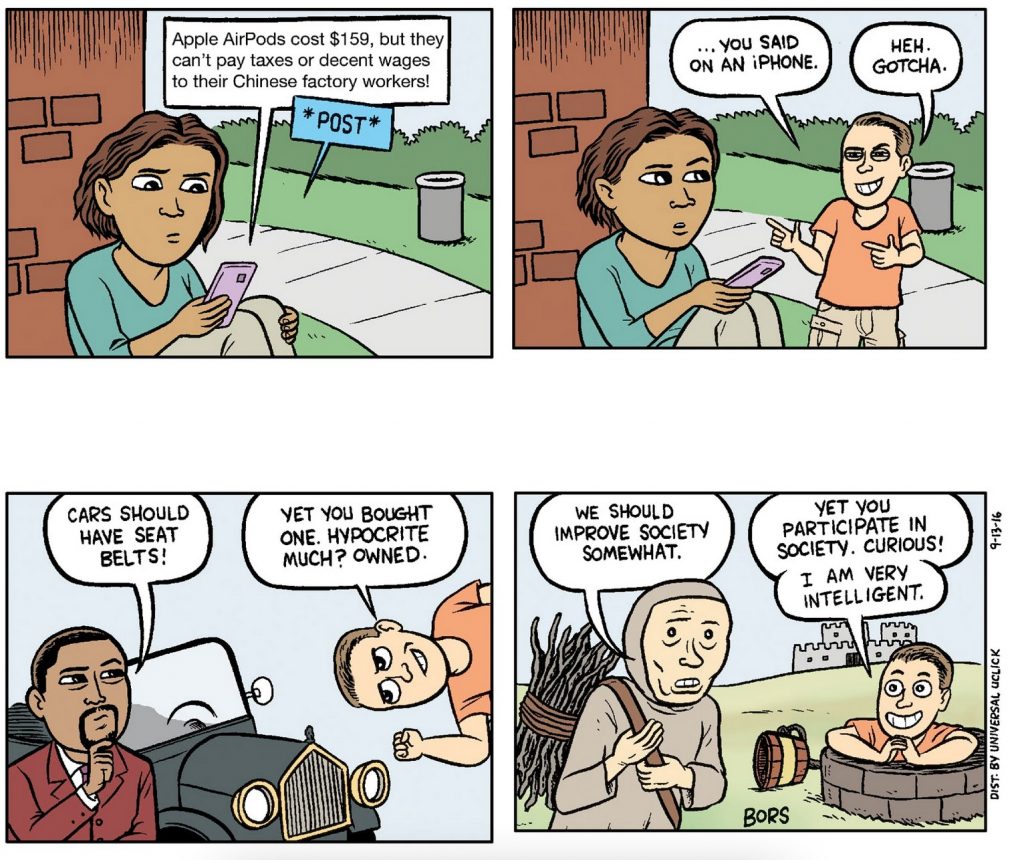

Team Plasma is hypocritical, yes—because some of them want to use Pokémon as their tools. Team Plasma is not hypocritical for battling, however. To say so is no different than patting yourself on the back for stating that people who point out societal issues still do indeed “live in a society.”

In Matt Bors’s iconic comic, “Mister Gotcha,” Bors illustrates that the nonsensical ones are those who put forth such bad faith arguments. Each panel showcases a different example of this. In the third panel, a man from the early 1900’s notes that cars should have seat belts. “Yet you bought one. Hypocrite much? Owned,” says Mister Gotcha.21 But in a world where cars are practically a necessity to get to and from work—another necessity—the man can’t be faulted for buying a car, and he is hardly a hypocrite for pointing out that seatbelts would benefit everyone. In the meantime, however, he’s going to have to make do, driving his unsafe, seatbelt-less car. A more modern application would be a car owner pointing out the dangers of fuel emissions—but without their car, they can’t get to work and therefore can’t pay their mortgage.

For Team Plasma, there’s no option but to prove their point by winning Pokémon battles. That doesn’t make them hypocritical—that’s simply how the world works. But if we’ve learned anything from Black and White, it’s that just because something is already a certain way doesn’t inherently make it wrong or right.

Team Plasma is a group torn apart, much like the state of matter it’s named after. Some members genuinely want to do good while the rest want to take advantage of others. But just like the real-world organizations and groups it draws inspiration from, the good intents of the few can’t absolve the group of its sins. As such, Team Plasma rightfully sees defeat in the end, serving as Black and White’s clear villainous threat despite the potential value of their goals.

Team Plasma is also bound by the laws of the world—laws that it seeks to change, but unfortunately must use along the way. Team Plasma, in its own way, represents the depth and complexity of Black and White: it’s both a simple team with a simple goal, and also highly nuanced and complex, far from simply black or white.

Although battles can be seen in a very literal sense—as a progression method, and as a competition to see who is stronger or who is “right”—battles can also be seen in a metaphorical way, just as most elements present in Black and White. Battles in Black and White ultimately represent the hardships we all go through and overcome to improve ourselves—to “level up,” if you will. That’s why Team Plasma will always be wrong—because we all need to experience challenges to grow, just like Bianca, Cheren, and even N. Separating people and Pokémon is the equivalent of separating any two groups of people who have differing opinions. Not being able to hear alternate ideas prevents you from learning anything new, expanding your horizons, and growing as an individual. In the Pokémon world, Pokémon act as the conduit for different ideas to pass through, with the conflict of battles bridging people together just like the conflict of considering opposing beliefs. With this in mind, Team Plasma’s goal to separate people and Pokémon gains a bit more merit—as many people would rather avoid conflict even if it’s for the benefit of one’s personal growth—while also becoming that much more important to stop.

But Team Plasma’s goal of putting an end to battles and Pokémon captivity still offer Black and White’s cast a profound conflict that pushes everyone to confront their own beliefs and challenge not just Team Plasma but themselves. Because you can say it’s clearly wrong to try to destroy the universe, or unleash an army of violent aliens upon the earth, or to drown the planet, and as such the perpetrators must be stopped. But can you really, truly say, without a doubt, that it’s wrong for Pokémon to be free?

Black and White are about considering different perspectives, and if Team Plasma’s perspective was any more tame, you’d find yourself not wanting to stop them—but if they were any more extreme, you’d hardly be willing to consider what they have to say. Within the confines of the Pokémon series formulas, Team Plasma is as morally ambiguous as they can be while also offering enough villainy to make a statement about extremist groups and ensuring that you have no qualms about putting a stop to their plans.