Part III: The Cast of Unova

Part III of our tribute to Pokémon Black and White focuses on each of the games’ many characters.

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Hilda and Hilbert | Juniper | Bianca | Cheren | The Gym Leaders | The Elite Four | Alder

Team Plasma Grunts | Concordia and Anthea | The Seven Sages | The Shadow Triad | Ghetsis | N

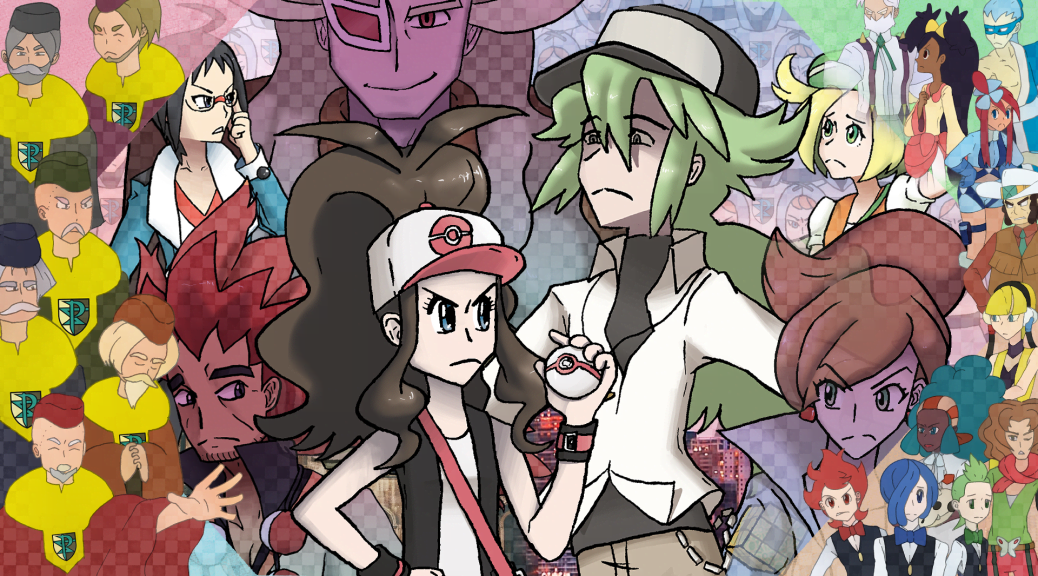

Hilda and Hilbert

What’s in a name? For the player character, who can choose whatever name they like, “default” names usually follow a very basic and narratively irrelevant theme. For instance, Calem and Serena from X and Y are named after the words “calm” and “serene,” appropriate descriptors for the France-based Kalos region, but hardly applicable to the games’ actual plot. Or consider the clever Elio, from the Greek sun god Helios, and Selene, from the Greek moon goddess of the same name, from Sun, Moon, Ultra Sun, and Ultra Moon. They are certainly befitting the game names and mascot legendary Pokémon, but not at all related to their stories.

So what’s in the names Hilda and Hilbert? As it turns out, quite a lot.

Hilda and Hilbert are Germanic games with the root hild, meaning “battle.” Their names in each language reference battle or war in some way, appropriate since battles are the mechanic the Pokémon games are built around. In fact, it’s that precise relevance that allows Hilda and Hilbert to have meaningful, rather than generic, names. Battles are the source of conflict in Black and White, the most blatant source of harm that can befall Pokémon, according to N. And in order to complete the game, the player must battle—Black and White‘s signature melding of gameplay and narrative.

Battles are the truth of the Pokémon series, and battling to grow closer to your Pokémon as well as your opponent are its ideal. For the player character, their name is their everything, as the protagonist silently advances through the region, following the scripted sequences with nothing to say and nothing to do but battle whoever stands in their way. The silent protagonist’s only method of communication is battling—and in Black and White, communication’s ability to help people understand one another and their unique perspectives is a heavily enforced theme. Once again, the games interweave gameplay and narrative in a subtle but meaningful way.

And as is to be expected of nearly everything in Black and White by now, digging just ever so slightly beneath the surface reveals a wealth of hidden depth. Hilda and Hilbert’s Japanese names—Touko and Touya, respectively—similarly reference the word “battle.” In this case, one of the readings for the kanji “fight” or “war” is tou. It’s seen in words such as toushi, “fighting spirit,” and used in alternative—uncommon—”spellings” of tatakau and tatakai, the verb and noun, respectively, of “battle.” But tou isn’t only found in battle.

The on reading for the kanji meaning “transparent” is also tou, and is used in the word for “transparent” or “clear,” toumei. In a world of black and white, being clear is quite notable. This transparency represents the lack of character, the protagonist historically being a “self-insert” that players can project themselves onto thanks to their lack of defining characteristics, mannerisms, and dialogue.

Compared to colors, which appear to the human eye when light particles are absorbed and others are reflected back, transparent objects have no light scattering and can be seen through. In addition to reflecting their nature as blank self-inserts, transparency indirectly references the player’s inability to be affected by the goings-on of the games, at least not in a way that allows them to alter the story. No matter how much one grows to sympathize with N’s plight, they must continue onward and defeat him to “win the game.” The plot goes right through this transparent body—it’s only the real, physical player on the other side of the screen who can emotionally respond to the story of the games. Because no matter how deeply moved a player is by any game, by any story, even a self-insert isn’t really them.

Although the “tradition” of canonically naming the protagonist after the games ended in the third generation—technically in the second with the release of HeartGold and SoulSilver and the renaming of Gold to Ethan, leaving rival Silver and Crystal-exclusive Kris to carry the torch—Black and White, as we will find, allow the rivals to bear the weight of the games’ names, both being incredible and crucial characters in their own right. All the while, the player’s role is emphasized through both battle and transparency, whose part to play is unchanged as the game marches forward. As N makes clear in Chargestone Cave, the player is “not swayed either way” compared to Cheren’s “black” and Bianca’s “white”—they’re “more of a neutral presence. Which is apparently a good thing.”

More than being good, it’s a necessity. As early as Accumula Town, NPCs fill you in on the history of Unova, its lore that Ghetsis is driven to recreate. N’s goal—an offshoot of Ghetsis’s—is to recreate the legend of the founding of Unova. “It’s my turn to become that hero,” the hero who created the Unova region. And N succeeds—as is oft repeated, the dragon that founded Unova sides with him, the dragon that matches the game’s name and the region’s state, be it futuristic or traditional.

But what about the player? In the Pokémon series, the player is thrust into great peril by chance, their purity and kindness giving them the strength to prevail over substantial evil with their Pokémon by their side. Black and White translates this into a theme of destiny, in line with the sculpting of Pokémon formula mainstays into narrative elements. The player’s kindness towards Pokémon moves N, and N—the hero—chooses you as his counterpart to face off against in a battle of convictions.

Still, why you? Why not Bianca, who suffered through defeat after defeat but still never gave up searching for her calling? Why not Cheren, whose views got turned upside down and bettered himself both as a person and as a Trainer as a result? Why not Alder, the wise mentor who has experienced both joy and loss and, despite neglecting his duties, is still considered the strongest—and perhaps even the kindest—Trainer in the entire region?

On the surface, a simple matter of gameplay gives the player the most active role in any Pokémon game. Imagine if the legendary dragon chose Alder, and as a result he could defeat N at the summit of the Pokémon League. You would arrive there, N would retreat, and maybe you could battle Alder before the credits roll—but what about the epic final battle against the villain that’s been building up for all this time? This scenario would be the letdown of the century.

Like yin and yang themselves, the villain cannot exist without the player in a video game. Only the most complexly woven video game tales can get away with a player that is not the protagonist, and Pokémon is rightfully kept simple to not only appeal to a very broad audience, but to keep in line with its established traditions. As a result, both N and the “mascot” legendary of the player’s game “choose” the player. They’re a hero by choice in the “meta” sense, as they choose what game to buy and choose to continue playing it until the end. But within the confines of the narrative itself, the player is destined to be a hero.

It doesn’t matter how much the player agrees or disagrees with N. It doesn’t matter how much stronger their convictions are compared to his. It doesn’t even matter how kindly they treat their Pokémon teammates—they could all have the lowest possible “friendship” stat, and it would make absolutely no difference. The player character is neutral, completely clear narratively. No matter how you choose to self-insert, the end result is the same. The mascot legendary will awaken. You will face off against N. And no matter how strong—or weak—your convictions, you will defeat both him and Ghetsis. Your individual light will pass through the clear player “character” as you continue through the predestined story. This is the destiny of all mainline Pokémon games thus far, and as such, Black and White take the opportunity to morph it into an intentional reference.

But Black and White choose to imbue gameplay necessities with even more narrative relevance than that. In the heat of the moment, the final three showdowns in N’s Castle are a thrilling climax to the story that has built up thus far, but taking a step back, there’s something very peculiar happening. The player has the stone, yet it doesn’t awaken after obtaining the final badge, nor after defeating the Elite Four, and not even after N defeats Alder and raises his castle. The exterior isn’t a suitable place for the legendary dragons to clash, according to N, but what about when you first step foot inside? Facing down the sages, it’s the Gym Leaders who must back you up, as your dragon remains dormant. After all that proof that you are both a worthy Trainer capable of defeating the region’s best, and a kind individual with wonderful friends who will help you in your time of need, you still aren’t deemed a “hero.”

So what does it finally take? Only when N in his throne room calls his dragon to his side does your stone begin to stir.

On the surface, your dragon only awakening in response to its other half is a simple way to keep the story’s tension building as you reach the finale. If you already had your dragon before this, you wouldn’t feel as nervous going into N’s Castle. There is, however, more meaning to this narrative decision than first meets the eye.

Looking at Pokémon game narratives from a purely surface level, there is always a matter of chance involved: you just happen to be traveling at the same time that an ecoterrorist group is trying to mess up the world’s weather. It’s pure coincidence that you meet Lillie and could help Cosmog on the bridge. It reasonably could have been anyone else in those positions—and that is, in fact, portrayed in the games themselves, albeit in a somewhat indirect way: “you” may be the player character, but so is everyone else who plays the games.

The player character, the game’s own protagonist, is a stand-in for the person on the other side of the game screen, but they are also representative of the myriad of people who could have done all of this instead. It is “destiny” that you go on this adventure, meet these people, and save this world, but the Pokémon series advocates for the innate goodness in people. If it wasn’t you who was there at the right place and the right time, it really would have been someone, anyone, else, because the world is filled with good, kind people who want to help others when they can.

On a metatextual level, the player is “chosen” in Black and White to move the story forward, as must always happen in any Pokémon game—in any game in general, in fact. But it’s retooled in this case to fit the story’s themes. Narratively, the player is “chosen” only by N. N sees the player’s kindness towards Pokémon, and he does admit that he sees this in other Trainers, too. But the player was the very first person to display this to N. It was simply by chance, but that doesn’t lessen its impact or importance in the slightest.

Although under the pretense of “heroes” and “legends,” no doubt influenced by N’s thorough brainwashing to believe he was the hero of Unova, N still “chose” you to be his rival, his equal, the only one who could possibly prove him wrong. Just as we choose our precious Pokémon partners to accompany us throughout our journey, we also, as we get older and grow more independent, can choose the people we associate with and are influenced by.

Our very selves are defined by the people around us: the people who teach us, help us, challenge us. In that same way, we are only a “hero” in Black and White because N chose us to be one—and as such, our dragon does not awake from its slumber until we are face to face with N and his own dragon. The dragon chooses us because N chose us first.

At first, we are clear. But as we learn from others and experience all the world has to offer, that transparency gets filled with tiles of black, white, and other colors. We are a collection of influences, a mosaic that can always allow for more tiles from other people, and in many cases, you will have only met those people by chance. And as your mosaic grows, you’ll also learn how to remove past tiles when necessary. It’s a “good thing” that you are “more of a neutral presence,” because it allows you to welcome differing opinions and continue to grow as a person rather than stubbornly stagnate.

Your clearness will one day be covered by colored tiles—in Black and White, Hilda and Hilbert’s clearness is slowly filled in by connecting with other people through battle. The resulting mosaic, completely unique for each person, is absolutely beautiful.