Part III: The Cast of Unova

Part III of our tribute to Pokémon Black and White focuses on each of the games’ many characters.

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Hilda and Hilbert | Juniper | Bianca | Cheren | The Gym Leaders | The Elite Four | Alder

Team Plasma Grunts | Concordia and Anthea | The Seven Sages | The Shadow Triad | Ghetsis | N

N

All life begins in darkness. Our lives are spent searching for light, working towards our own truths and happiness. But in the story of our lives, of which we are our own main character, there is always a supporting cast. Some cast members are fleeting, appearing for the equivalent of less than a page. Others become long-term deuteragonists who support us throughout numerous chapters of our journeys. Others still will stand in our way as antagonists. Each of these cast members is connected in a complex web, like hexagons all aligned, each playing their own crucial part in shaping our stories.

N’s journey brings him into contact with many different characters, all of whom serve a different role. The formulas of the Pokémon world provide it with the structure it so enjoys. It’s easiest to box characters into archetypes: rival, Gym Leader, Champion, villain, generic Trainer. But N is complex; much like most people, he can’t be boxed into just one category. He is just as much a rival as he is a villain and even Champion.

But what makes N any of these things? Certain Pokémon series archetypes are easy to recognize thanks to Trainer classes: the Champion title only goes to the game’s Champion, while villains get labelled with their team’s name in some way. But how does Pokémon distinguish rivals? In practicality, “rival” is a story-based title more than anything. As such, when not relying on non-main series media for clarification, who is and isn’t a rival can, in fact, be argued. There is no “Rival” Trainer class, with most characters that fans consider—and outside sources confirm—to be rivals using the class “Pokémon Trainer.” Even more interestingly, in the first two generations of Pokémon games, rivals Blue and Silver had no Trainer classes at all. Blue doesn’t even get a class when he battles as the Pokémon League “champion”—which, in generation one, wasn’t even a proper noun yet.

But what makes N any of these things? Certain Pokémon series archetypes are easy to recognize thanks to Trainer classes: the Champion title only goes to the game’s Champion, while villains get labelled with their team’s name in some way. But how does Pokémon distinguish rivals? In practicality, “rival” is a story-based title more than anything. As such, when not relying on non-main series media for clarification, who is and isn’t a rival can, in fact, be argued. There is no “Rival” Trainer class, with most characters that fans consider—and outside sources confirm—to be rivals using the class “Pokémon Trainer.” Even more interestingly, in the first two generations of Pokémon games, rivals Blue and Silver had no Trainer classes at all. Blue doesn’t even get a class when he battles as the Pokémon League “champion”—which, in generation one, wasn’t even a proper noun yet.

Despite this, the rival as an archetype comes from the very first generation. Prof. Oak describes Blue as “your rival since you were a baby,” and Blue reciprocates the sentiment by calling the player his “rival” at the Pokémon League. In generation two, Silver exhibited some similar traits as Blue, including an antagonistic attitude and picking a starter Pokémon with a type advantage against your own. Although he never becomes a Champion the way Blue does, their similarities, plus the repeated mechanical purpose of frequent battling, made it clear that rivals would be a recurring part of the Pokémon series formula.

But generation three shook things up. Not only are there two rivals, but neither Wally nor Brendan or May, depending on the player’s chosen gender, is antagonistic towards the player. Wally also doesn’t choose a starter Pokémon based on the player’s, instead catching a Ralts in the wild. Brendan and May, who do pick a starter advantageous to your own, don’t battle you enough times throughout the game for it to fully evolve. Despite this, it took the fandom at large until generation three’s remakes to finally agree that Wally, who battles the player outside the Pokémon League, is just as much a “primary rival” as Brendan or May, who even in Emerald don’t challenge the player past Lilycove City.

Generation four’s return to basics with Barry, who fights you frequently with a fairly formidable team, still isn’t one-to-one with the series’s first two rivals. Barry’s character is quite competitive, but he’s hardly antagonistic the way Blue and especially Silver are. These examples indicate that, even prior to Black and White, the rival archetype wasn’t strictly bound by personality or even starter Pokémon. The only consistency they share is in their “purpose:” to serve as a routine opponent throughout their games with some amount of competitive edge.

Generation four’s return to basics with Barry, who fights you frequently with a fairly formidable team, still isn’t one-to-one with the series’s first two rivals. Barry’s character is quite competitive, but he’s hardly antagonistic the way Blue and especially Silver are. These examples indicate that, even prior to Black and White, the rival archetype wasn’t strictly bound by personality or even starter Pokémon. The only consistency they share is in their “purpose:” to serve as a routine opponent throughout their games with some amount of competitive edge.

As a result, it’s easy to consider N as one of your rivals in Black and White, even without consulting outside material such as Pokémon Masters EX. N’s role as rival may be obfuscated by his emphasis on leading Team Plasma, but he does fit elements of the archetype all the same.

N’s status as a rival is also enhanced when examined in comparison to the player’s other rivals. At first glance, he seems to have more in common with Cheren than Bianca: both Cheren and N are skilled Trainers aiming for the position of Champion. Where they differ is in their purpose: Cheren doesn’t have a reason to want to become Champion other than for the title, which represents ultimate strength. N wishes to become Champion to attain the ethos that will help him convince others to free their Pokémon.

In this relationship, Cheren is the black to N’s white: Cheren is entirely stuck in the past, when Pokémon games were about fulfilling obligations. Players are obligated to become the Champion because the games are obligated to have Gym Leaders and a championship bout at the end. As a result, Cheren doesn’t know what he’s fighting for. It’s compulsory for him to seek the title of Champion, but that also likens it to nothing more than a chore.

N, on the other hand, is trying to move towards the future—a future where things are different. But there’s only so far he can realistically go in the confines of the Pokémon world: it would be nice if the games could expand beyond the “Catch Pokémon, Battle Gym, Battle Champion” formula, but to separate people and Pokémon altogether would be to end the franchise entirely. Even the Mystery Dungeon crossover games, with casts comprising of only Pokémon, make reference to Trainers, which some Pokémon themselves once were. People, Trainers or not, are the yin to Pokémon’s yang—you simply cannot have one without the other.

You also can’t have a Pokémon game without music. Cheren’s encounter theme song is “Cheren’s Theme.” This is very standard titling from Pokémon‘s past into its present. Games with only one rival, or a rival who can be named freely, will usually opt for some variation of the title “Rival Encounter” or even just “Rival.” Games with multiple rivals will title their encounter themes after their name. Rivals are very special characters, and the music tied to them is equally so, even if their titles don’t reflect that. “Cheren’s Theme” is an upbeat banger with flashy staccato that feels fitting for someone who is serious, but not so aloof as to be entirely distanced from you. It has a bite to it, similar to the songs for more traditional rival characters, such as generation four’s “Rival,” or the songs titled “A Rival Appears” in both generations one and two.

Villains usually get the same titling treatment for their encounter songs, such as “Guzma’s Theme” in generation seven and “Leader’s Theme” shared by both Maxie and Archie in generation three. Although it seems logical that N, who is both a villain and a rival, would follow suit with both standards, he instead, like much of Black and White, deviates from the norm: N’s encounter theme is titled “Prisoner to a Formula.” Just as Cheren finds N’s rapid speech—and the Pokémon liberation he speaks about—strange during their first encounter, “Prisoner to a Formula” is also strange. It’s a waltz with a music box-like melody drifting atop whimsical pizzicato strings and an oboe. There’s undoubtedly a sense of innocence, even whimsy, emanating from “Prisoner to a Formula,” but it’s not entirely civil, either. It, too, has a bite to it like “Cheren’s Theme,” a sense of conflict brewing just underneath the surface. The sense of conflict stems from the formulas of the Pokémon world, which dictate that this encounter theme plays before you and N face off in battle.

N doesn’t hide his fascination with formulas from the player. In Chargestone Cave, he muses that “Formulas express electricity and its connection to Pokémon… If people did not exist, this would be an ideal place.” He also believes that there is an “equation that will change the world,” and by the time his castle rises at the end of the games, he believes he has solved it. But how can someone be a “prisoner” to something they love? As it turns out, quite easily.

“I have a future I must change,” N claims. Without even consciously thinking about it, we all know what the future holds: in Black and White‘s future, N will be defeated, and Pokémon and people will remain together so long as there are additional Pokémon games to be made.

N’s dialogue in Nimbasa City references this singular future, first with N admitting that, “Perhaps I can’t beat you here and now, but I’ll battle you to buy time…” As the inevitable battle that follows begins to wind down and N’s defeat is imminent, he thinks out loud, “Even if I lose, is it different from the future I saw?” And as his final Pokémon falls, he confirms that, no, it wasn’t any different: “The result was the same…” From the start, N recognizes that he must lose in order for the story to progress—something Cheren and even the less battle-focused Bianca struggle to accept at first. And the story’s progression is the only way N may move closer to achieving his goal.

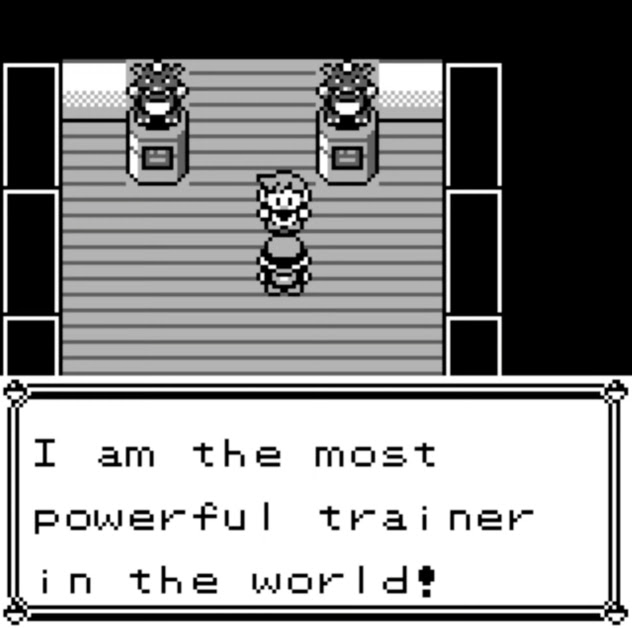

Pokémon characters frequently bounce back from loss. In Red and Blue alone, repeatedly beating your rival Blue has no bearing on his superiority complex. He even calls himself “the most powerful Trainer in the world” when he defeats Lance, even though it should be obvious by then—after losing to you six or seven times already—that he really isn’t the strongest even on a good day. Team Rocket’s Boss Giovanni also doesn’t stay down after his trouncing in the Rocket Hideout and Silph Co.; it’s only after beating him in the Viridian City Gym that he disbands Team Rocket. Other team bosses throughout the series behave similarly, only giving up after being defeated at their highest point, even though, to the player, it’s obvious that they will fall eventually. Each of the battles against them serve as steps to solve the formula of completing the game at hand. The variables that go into these equations are the Pokémon on your team—but regardless of the variables in question, the result is the same.

Pokémon characters frequently bounce back from loss. In Red and Blue alone, repeatedly beating your rival Blue has no bearing on his superiority complex. He even calls himself “the most powerful Trainer in the world” when he defeats Lance, even though it should be obvious by then—after losing to you six or seven times already—that he really isn’t the strongest even on a good day. Team Rocket’s Boss Giovanni also doesn’t stay down after his trouncing in the Rocket Hideout and Silph Co.; it’s only after beating him in the Viridian City Gym that he disbands Team Rocket. Other team bosses throughout the series behave similarly, only giving up after being defeated at their highest point, even though, to the player, it’s obvious that they will fall eventually. Each of the battles against them serve as steps to solve the formula of completing the game at hand. The variables that go into these equations are the Pokémon on your team—but regardless of the variables in question, the result is the same.

N understands that it’s okay to lose some battles along the way to his goal of dethroning the Champion. But just because he recognizes the inevitability—the requirement—of loss doesn’t make matters any better for him. N is, in the end, a prisoner to the formulas of the Pokémon world. No matter how pure his ideals or what truths he’s built them on, he, as both a rival and the game’s antagonist, can never truly succeed. No matter what variables you put in, there is only one possible solution to Pokémon‘s equation, and that is the player’s victory.

At first glance, N and Bianca don’t have much in common. N even describes Bianca as being simply unable to become stronger, while it’s clear that N is one of the region’s strongest Trainers. But just like with all people, they have more in common than they think. Many of those similarities come from their innocence about “the real world,” brought about by their respective fathers. As poet Mary Oliver describes in her essay collection Upstream, “I had to go out into the world and see it and hear it and react to it, before I knew at all who I was, what I was, what I wanted to be.”1 Indeed, how can anyone know who they are without having any sort of comparison points to go off of? How can they know what they want to be without knowing what options exist? And how can anyone know what those options are without going out into the world and discovering them? With familiarity comes a sense of safety, but not only does that safety turn out to be false, it also brings about stagnation.

Bianca and N start encountering unfamiliar things right as Black and White begin. To Bianca, high-tech PCs are just as foreign as the endless number of different career paths available to her. For N, meeting Pokémon who love being with their Trainers and Trainers who would do anything to protect their precious Pokémon completely shatters his preconceived notions. The real world’s sky isn’t bright blue with white clouds like his room’s wallpaper—it’s darkening with an oncoming storm. What he’s discovering goes against his very core beliefs, and he doesn’t have the tools to process any of it.

N may be the white to Cheren’s black, but he’s the black to Bianca’s white. Thanks to knowing the player and Cheren since childhood, Bianca knew there were more possibilities for her out in the real world. This gives her the resolve to disobey her father, make her escape, and find new colors to paint herself with. N’s upbringing, however, was so deliberately curated by Ghetsis that he struggles to adapt to a reality that goes against his foundational beliefs. Ghetsis has already painted N black, the color that is the most challenging to alter. And he did so by making sure N’s “world” was as small as possible, limiting his beliefs and his ability to expand them.

To expand our understanding of Black and White‘s major characters, we can once again look to its music. “Bianca’s Theme” is light and jovial, consisting of mostly higher-pitched, twinkling notes. Just by listening to their encounter themes, it’s clear who between Bianca and Cheren is less serious about battling. “Bianca’s Theme” is also less hostile than “Prisoner to a Formula” thanks to the latter being in minor key and its occasional use of staccato notes. But as appropriate as Bianca’s theme is for her, it doesn’t “say” much about the serious turn her character arc takes. That is instead left to “An Unwavering Heart,” the melancholic melody that makes its first audio appearance when Bianca confronts her father in Nimbasa City.

To expand our understanding of Black and White‘s major characters, we can once again look to its music. “Bianca’s Theme” is light and jovial, consisting of mostly higher-pitched, twinkling notes. Just by listening to their encounter themes, it’s clear who between Bianca and Cheren is less serious about battling. “Bianca’s Theme” is also less hostile than “Prisoner to a Formula” thanks to the latter being in minor key and its occasional use of staccato notes. But as appropriate as Bianca’s theme is for her, it doesn’t “say” much about the serious turn her character arc takes. That is instead left to “An Unwavering Heart,” the melancholic melody that makes its first audio appearance when Bianca confronts her father in Nimbasa City.

Bianca’s father is cruel and controlling. He frequently yells and doesn’t allow Bianca to go out on her own. His good intentions of keeping her safe from the difficulties and challenges that come from independence are nullified by the harmful outcomes she endures. When it’s no longer the ceiling of her home but a cloudless sky over Bianca’s head, she has no tools to help her navigate which direction to go, and she struggles in a completely different way than her father anticipated.

What makes Bianca’s father forgivable isn’t the intention behind his initial action but his willingness to change. Or, as LICSW Patrick Teahan puts it, “What makes [someone] toxic [are] the hills they will die on.”2 In Nimbasa City, Bianca’s father recognizes his wrongs and respects Bianca’s decision to travel. He even welcomes her to return home whenever she feels like she needs a break. Bianca’s dad initially tried to keep her locked away for the safety of her future, but is eventually willing to let her be independent for that very same sake. By the end of the game, it’s clear that Bianca’s parents will give her the time and space she needs to figure out her own destiny—and the support she needs if she ever finds herself in trouble. Just because you’ve “grown up” doesn’t mean you can’t return home to the love and support of your family.

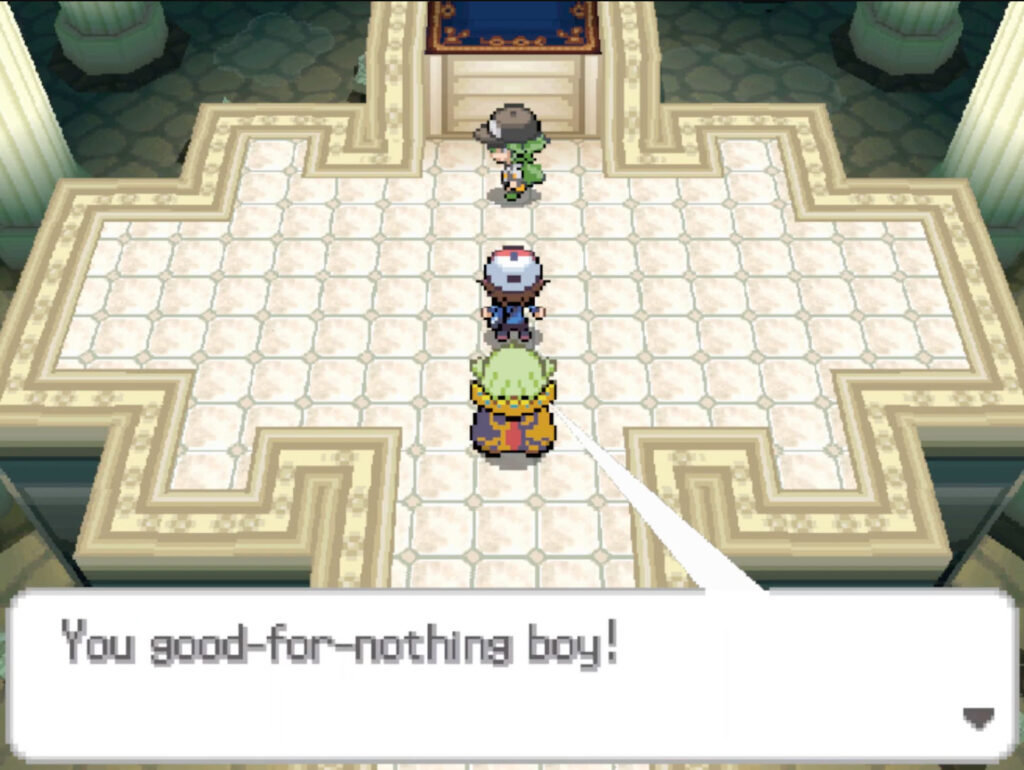

When N fails to defeat the player at the end of Black and White, Ghetsis doesn’t offer the kind of support that is expected of a parental figure. Instead, he starts verbally assaulting N while “Ghetsis’ Ambitions” roars in the background. While “An Unwavering Heart” manages to sound both gentle yet pained, encapsulating the uncertainty that comes with conflict over the future, “Ghetsis’ Ambitions” is frightening, dramatic, and, most of all, entirely confident of itself and its outcome. These two tracks may sound like total opposites, but in title they’re surprisingly quite similar: Ghetsis is certainly unwavering in his ambitions.

Just as Elesa had to step in to help talk some sense into Bianca’s father, the player has to interject during Ghetsis’s abuse session. But where words worked to sway Bianca’s dad, battle must occur to stop Ghetsis. It’s more than abundantly clear that he is beyond reasonable discussion and unwilling to—and undeserving of—compromise. He opted to keep N trapped in the past, under the guise of roleplaying as an ancient hero, not to protect N from any particular danger, but for the benefit of Ghetsis’s future as the world’s ruler.

The matter of who truly benefits from isolation is paralleled in the Victini subplot in Liberty Garden. Victini’s previous owner was trying to keep it safe from people who would use it for evil, and probably believed that even good-hearted people would negatively succumb to its power. To prove him right, there’s a generic NPC in the area who mumbles about how he would have taken Victini for himself had he known where it was.

But what Victini’s owner did was lock it away from the rest of the world. This cruel and unforgivable solution only gets worse when you realize it took 200 years for anyone to find and free Victini. The owner may have given Victini some toys and furniture, but remaining in an unchanging environment and with no one around for two centuries is flat-out torturous. And while hiding Victini away and making sure no one knows about it keeps it safe for the time being, it also means that if anyone does find it, it’s even easier to steal. Team Plasma was stopped only because they took the island’s visitors hostage and drew attention to themselves. Wait for everyone to leave and then steal Victini, and no one would be any wiser to what happened. Victini would be left to fend for itself, all alone, without any practical battle experience in 200 years. We see what just a few years of not battling does to Champion Alder’s skills—and appropriately, Victini is only Level 15 in the Liberty Garden.

But what Victini’s owner did was lock it away from the rest of the world. This cruel and unforgivable solution only gets worse when you realize it took 200 years for anyone to find and free Victini. The owner may have given Victini some toys and furniture, but remaining in an unchanging environment and with no one around for two centuries is flat-out torturous. And while hiding Victini away and making sure no one knows about it keeps it safe for the time being, it also means that if anyone does find it, it’s even easier to steal. Team Plasma was stopped only because they took the island’s visitors hostage and drew attention to themselves. Wait for everyone to leave and then steal Victini, and no one would be any wiser to what happened. Victini would be left to fend for itself, all alone, without any practical battle experience in 200 years. We see what just a few years of not battling does to Champion Alder’s skills—and appropriately, Victini is only Level 15 in the Liberty Garden.

Bianca’s father is quite similar to Victini’s owner. He doesn’t realize that trying to keep Bianca away from the challenges of the real world only makes her less capable of protecting herself when danger does arise. This is most prominently shown when Bianca’s Munna is stolen by Team Plasma in Castelia City, and she needs the help of others to retrieve it.

Ghetsis’s approach is a bit different, however—he specifically prepared N to become the strongest Trainer possible. And he did, in fact, succeed: N is perfectly capable of fending for himself when it comes to Pokémon battles. It’s a different kind of conflict that N doesn’t know how to handle: opinions and evidence that go against his worldview. For Ghetsis, this is all according to plan. The more unshakable N’s beliefs, the less willing, and in a way, capable, he will be to adapt and even change them. But this is just one of the ways past childhood trauma, specifically from a toxic family system, manifests in a grown person’s present behavior and beliefs.

Abuse is a cycle that can seem as unbreakable as the seasons. In many cases, such abuse is far more subtle than the blatant cruelty of Bianca’s father or Ghetsis, making it even trickier to suss out the causes of childhood trauma. But for Bianca and especially for N, their father figures serve as an example of the ways that the past can continue to have a stronghold on the future until those in the present actively work to break free.

Breaking free is never easy. The damage done in a single childhood can take a lifetime to heal. And even then, healing in reality isn’t as simple as it is in a Pokémon battle: scars will remain in the form of memories, intrusive thoughts and beliefs, or even in a physical form that can continue to influence the present and future despite our best efforts to keep them in the past.

The character who attempted to lock N into this horrendous cycle was the very first major character of his life’s story: Ghetsis. Ryoku claims that the sages “haven’t even figured out if [Ghetsis and N] are father and son.” Still, the biological relation or lack thereof between the two doesn’t change the fact that Ghetsis is N’s father figure who raised him from childhood. And he raised N in a world shaped entirely by his own hand.

“That room was the world that was provided to our lord N…” So says the Shadow Triad member just outside N’s room within his castle. But no one’s entire world should be confined to a single room; even Bianca’s father allowed her to visit her friends back home.

And confined N was: locked to a single room in an underground castle, N couldn’t catch even the slightest glimpse of the real world outside. Instead, his room pretends to be the real world. The wallpaper is patterned with clouds, just as Unova is tessellated with clouds both literal and metaphorical, its towns and cities named after clouds in English and patterns in Japanese. But this is not the real sky. This is not the real Unova. It is all the creation of Ghetsis, the man believing himself to be God.

N is a clear parallel to Victini: the latter was hidden away in an unchanging, toy-filled environment to prevent others from accessing its power to bring surefire victory. N was hidden away in an unchanging, toy-filled environment to hone his latent power, to become the ultimate puppet guaranteed to bring victory to Team Plasma and fulfill Ghetsis’s ambitions.

N is a clear parallel to Victini: the latter was hidden away in an unchanging, toy-filled environment to prevent others from accessing its power to bring surefire victory. N was hidden away in an unchanging, toy-filled environment to hone his latent power, to become the ultimate puppet guaranteed to bring victory to Team Plasma and fulfill Ghetsis’s ambitions.

And Ghetsis is certainly ambitious. Although the scope may be small, he is already capable of creating entire worlds and controlling the person within them. What’s to stop him from expanding his scope and controlling all of Unova? The only difference between N’s room and Ghetsis’s ideal Unova is the size of the box each one can fit into.

Strip away all the instruments besides the music box of “Prisoner to a Formula,” the theme of N in his present, and you get “The Pokémon Child, N,” the haunting melody of N’s past. Now the innocence that permeated “Prisoner to a Formula” is laid bare. You’d think it would be perfectly fitting for a room filled with only children’s toys, but the song instead fills the room with an unsettling feeling. Before even getting to examine the contents of the glorified box of N’s room, its very music fills the player with unease, telling them something is terrifyingly wrong. As Concordia says, “There is nothing more beautiful and terrifying than innocence.”

Innocence is untouched, dangerous in how easily it can be manipulated by the influence of others, no matter how good or bad their intentions. Symbolically, children can represent both “purity” and “innocence”3 because they are uninfluenced. N’s childhood before being abducted by Ghetsis is more representative of this than the typical child, as he grew up in a forest away from people and, thus, their biases. The room N was brought to once Ghetsis abducted him keeps this theme relevant in the present. Although the room is fit for a child, inspecting the toys reveals that they’re new, indicating that Ghetsis kept N trapped not only in this singular room but in a perpetual childlike state, never replacing his toys with anything more age-appropriate. And there is an almost childlike purity to N throughout the game: he refers to Pokémon as his “friends” and the act of catching them as “befriending” them, even when talking about the legendary dragon.

Innocence is untouched, dangerous in how easily it can be manipulated by the influence of others, no matter how good or bad their intentions. Symbolically, children can represent both “purity” and “innocence”3 because they are uninfluenced. N’s childhood before being abducted by Ghetsis is more representative of this than the typical child, as he grew up in a forest away from people and, thus, their biases. The room N was brought to once Ghetsis abducted him keeps this theme relevant in the present. Although the room is fit for a child, inspecting the toys reveals that they’re new, indicating that Ghetsis kept N trapped not only in this singular room but in a perpetual childlike state, never replacing his toys with anything more age-appropriate. And there is an almost childlike purity to N throughout the game: he refers to Pokémon as his “friends” and the act of catching them as “befriending” them, even when talking about the legendary dragon.

Children “can also stand for mystic knowledge,”4 another trait associated with N and his supernatural ability to speak to Pokémon. Finally, the child can represent “openness to faith,”5 just as their uninfluenced natures make them open to accepting ideas without question. They simply don’t know enough yet to know what to doubt and what to believe. If someone with enough ethos, such as a parental figure, “teaches” them something, they are almost certain to take it to heart.

We generally think of this process of absorbing outside influence as removing innocence. It can instead, however, lead to a different kind of innocence, one in which a lack of knowledge, experience, or understanding prevents someone from seeing how their beliefs may be built upon false notions or may even harm others. Once N was taken to that room where no other ideas could reach him, he had no means of questioning Ghetsis’s teachings. Without knowing that there are in fact kind Trainers in the world, how else was N supposed to interpret the unending succession of abused Pokémon Ghetsis brought to him? This upbringing combined with N’s unwavering dedication to keeping Pokémon safe, leading him to behave antagonistically towards people outside of Team Plasma. It even clouded his ability to question Ghetsis’s true motives.

Concordia attributes both “kinds” of innocence to N, saying, “N was touched by [the abused Pokémon’s] plight, and started pursuing [his goals], thinking only of Pokémon. N’s heart is pure and innocent.” And there’s good reason why N “think[s] only of Pokémon:” as the sole human raised in a forest full of Pokémon, N is literally “The Pokémon Child.” And in the same way that abuse survivors “raise themselves” due to their family’s negligence,6 N was still raised by Pokémon even after Ghetsis abducted him. The abused Pokémon that Ghetsis brought to “teach” N were the ones who “looked after him” in his room. They, together with the Pokémon of the forest, who N thought were happy because there were no other humans around, confirmed to N what Ghetsis wanted him to believe.

Concordia attributes both “kinds” of innocence to N, saying, “N was touched by [the abused Pokémon’s] plight, and started pursuing [his goals], thinking only of Pokémon. N’s heart is pure and innocent.” And there’s good reason why N “think[s] only of Pokémon:” as the sole human raised in a forest full of Pokémon, N is literally “The Pokémon Child.” And in the same way that abuse survivors “raise themselves” due to their family’s negligence,6 N was still raised by Pokémon even after Ghetsis abducted him. The abused Pokémon that Ghetsis brought to “teach” N were the ones who “looked after him” in his room. They, together with the Pokémon of the forest, who N thought were happy because there were no other humans around, confirmed to N what Ghetsis wanted him to believe.

Ghetsis also wanted N to believe he was the chosen hero of Unova, but didn’t give him a name to match. For someone who has special titles for all his musical themes, N himself doesn’t have a distinct name. N, when lowercase, is instead one of the most common variables used in mathematics. N is, in the end, nothing but a variable in Ghetsis’s schemes, able to be replaced with anyone Ghetsis deems capable of serving as his puppet.

The catch, however, is that the person must actually fit into the equation. Ghetsis’s plan to convince the masses to release their Pokémon required making it seem like the hero of Unova had returned and also wanted Pokémon liberation. N’s ability to speak to Pokémon and his unyielding love for them was what made him the perfect person for this job. Ghetsis would no doubt make do if he had to replace N with someone else, but doing so would require changing the plan entirely. Someone like, say, Bianca, simply couldn’t pass as the hero of Unova. While the name “N” can be read as a replaceable mathematical variable—which is the way Ghetsis perceives him—variables can’t be replaced with just any value. Most of the time, there’s only one value a variable can be for the equation at hand to work.

This gives mathematics its perceived “black or white” quality: either the equation is correct, or it’s incorrect. One plus one is always two, and one plus one being anything besides two is wrong. This is why N loves equations so much: there is no “gray” when it comes to math. It’s correct or it’s incorrect. Either people are always cruel to Pokémon, or people always treat Pokémon well. There is no “sometimes.”

But life isn’t always so mathematical. As we well know, there are, in fact, always “sometimes.” People aren’t always cruel to Pokémon, and people don’t always treat Pokémon well. But we can’t separate people from Pokémon just because some people hurt Pokémon, just like we don’t stop people from caring for children just because some people—even parents—hurt children. Instead of slapping a bandage over the problem, we should try to understand the root causes behind why these problems happen. Then we can properly work towards a society where caregivers are knowledgeable and in the right mental headspace to raise their kids—or a society where people understand how to better work with Pokémon, not making their Pokémon simply work for them as tools. But for someone to know how to do that, and to unlearn what was taught by all the different traumas inflicted by the world, they must first step out of their cave.

N‘s childhood is almost a one-for-one replication of Plato’s allegory of the cave: his whole life was spent in an enclosed room, with no way to leave and discover what lay outside in the real world. Because of this, the only things he got to see were curated entirely by Ghetsis, giving Ghetsis free rein to instill into N false ideas of what reality entailed. When N finally gets to exit his room, he is confused, angered, and hurt when he sees Trainers and Pokémon living together in harmony, as it goes against everything that he knows.

Plato’s allegory of the cave is aptly titled: an allegory is a story that uses symbolism or metaphor to get its “meaning” across.7 But metaphor and symbolism can be interpreted in many different ways. This is paradoxically both ironic and perfect when it comes to Plato’s cave allegory, since one of its most common interpretations is how what we directly perceive isn’t always the strict truth. Our perception is highly flawed due to how easy it is to influence and how difficult it can be to tell that it’s been influenced at all. Everything is diluted through multiple filters before we finally get to “perceive” it ourselves. Those filters can come from the source portraying it,8 or they can come from within ourselves thanks to our preconceived notions and internal biases. Have you ever passed on trying food with a certain ingredient because you had a bad experience with that ingredient in a completely unrelated dish? Or have you perhaps convinced yourself that a video game was “bad” before even playing it because you saw that one of the monsters in the game was styled after soft serve ice cream? But two different people can perceive the exact same thing differently, so perhaps the world’s number one ice cream fan would find the aforementioned game to be the very best before it’s even released.

Most looks at Plato’s allegory tend to stop at this key idea. The full allegory, however, goes a step further to detail the duty of the person who can step out of the cave. The cave itself is one of the allegory’s symbols, however. There isn’t actually a physical cave that we can leave to find Forms, or the true, ideal, and unchanging version of things as discussed in the Shadow Triad chapter. In fact, Forms “don’t exist in our spatial and temporal physical world” at all, meaning we can’t perceive them with just our senses.9 To discover Forms, people must use their wisdom and essentially work backwards. Just like how Bianca discovers who she wants to be by determining what she can’t or doesn’t want to do, people can “perceive the World of Forms by recognizing” that what they perceive all around them are merely shadows.10

Doing so is no easy task, however, meaning only a true philosopher could manage it. Plato also insists that philosophers are “the only [people] who can be trusted to rule well”11 because they best “understand the true Forms of ideals such as friendship, goodness, truth, wisdom, virtue, and justice,” and can thus “integrate this knowledge … into the physical world.”12 As a result, the philosopher who leaves the cave must lead the rest of the people, teaching them the truths and ideals they’ve discovered in their pursuit of wisdom, justice, and goodness.

Both Alder and N think they are the philosopher king who has set out to teach everyone what they discovered about “goodness” when they left their caves. Alder feels he must teach Unova about the joys of simply being together with Pokémon as opposed to pursuing meaningless strength. N thinks he must teach Unova about how people are oppressing Pokémon and need to free them. Alder’s task is far easier, since his beliefs already mostly align with the status quo. N’s ideas are so opposed to the norm that they will be met with much more resistance, but even Alder still struggles to convince particularly battle-focused rivals to loosen up.

The resistance these two kings meet also stems from Plato’s allegory: after the philosopher sees the true world outside the cave, he returns to teach the remaining prisoners what he’s learned. What he says is so detached from the “reality” they’re accustomed to, however, that they can’t fathom any of his ideas and even threaten the philosopher with violence.13 Thanks to Pokémon, both Alder and N can defend themselves when met with resistance—although neither would like to. Like the rest of Team Plasma, N is generally subject to the criticism that he wants to free Pokémon yet battles with them. The defense for N is the same as it was for the Team Plasma Grunts: he has no choice because battling is the only way to get things done in the Pokémon world. Despite how naturally gifted he is at being a Trainer, the last thing N wants to do is engage in battle, but battle he must in order to defeat the Champion and gain the ethos required to convince others to release their Pokémon.

This does raise the question of whether that ethos would actually be enough to succeed at his goal. The answer is yes. Ghetsis’s two speeches in Accumula Town and Opelucid City had many onlookers who began questioning their beliefs with his words, and others who flat out agreed with him. Imagine, then, how influential it would be if the person who just defeated the Champion released his own Pokémon before telling everyone else that they should do the same. The Champion is thought of as the greatest Trainer in the region, a Trainer almost every person in the Pokémon world can only dream of defeating—and this victor against the Champion would be allied with the legendary dragon that founded Unova. N’s words and actions would be unfathomably influential by that point.

But surely N wouldn’t be so influential as to convince everyone to release their Pokémon, right? That’s true, but that’s also not a problem. All N would need is for some people to follow him at first. As Ghetsis explains, the number of people who release their Pokémon will grow over time, hexagons of one color flipping to take on the color of their neighbors as they’re surrounded on all sides. “In no time … [h]aving a Pokémon will be considered a bad thing! [People who want to keep their Pokémon] will be[come] unable to face public opinion and will release their Pokémon!” This is especially beneficial for N, who would rather not force people to see things his way. He won’t give up until everyone agrees, but he also won’t stoop to brute force the way Ghetsis would, and this method allows everyone to release their Pokémon of their own volition.

This kind of mentality can even be seen within the Pokémon fanbase itself: most fans didn’t think N could possibly be a rival until external media such as Pokémon Masters EX explicitly categorized him as such. Once a source that was deemed both significant and credible enough released the idea into the wild, more and more people started believing it themselves until it became nigh indisputable. What was once considered a fringe opinion less than a decade ago now seems like common sense. And as more and more people repeat the idea, the more believable—the more “correct”—it seems.

But N isn’t the only character who must convince others that his ideas are “correct” through battle even though he wishes not to. Alder abandoned the Pokémon League—and battling altogether—when his partner Pokémon died so he could pursue a leisurely lifestyle of teaching others how to live, laugh, and love their Pokémon. While he lucks out in not needing to battle Cheren when their beliefs don’t align, he isn’t so fortunate when N starts racking up Badges and beelining towards the Pokémon League. To protect the bond between people and Pokémon that he holds so dear, Alder must, for the first time in years, battle in an attempt to stop N in his tracks.

As these two would-be kings fight to defend their beliefs, we may wonder why it had to come to this at all. It can be almost impossible for people who haven’t experienced blatant indoctrination—or who have never really had their beliefs challenged—to understand just how difficult it is for someone in N’s situation to accept differing viewpoints. No one can possibly disregard what they’ve been taught at the drop of a hat, even when faced with evidence proving the contrary. Deconstructing such beliefs is essentially a lifelong process. As Anthea explains in N’s Castle, “Trainers battle to practice their skills and to grow in experience, but never to hurt their Pokémon. My lord N has realized this, deep down in his heart…but he has spent too much painful time here in this castle to admit it…”

Despite this, the only person N actively pushes away is Prof. Juniper. In Chargestone Cave, she says that “all people [should] get to decide for themselves how to relate to Pokémon.” It sounds reasonable, especially since we’re predisposed to believing that people and Pokémon should always be together. But if you applied that same logic to children, it would mean it’s okay for parents to inflict corporal punishment upon their kids or send them to work in the mines at age ten so long as that’s how they choose to “relate to them.” Parents who were raised that same way very well may perpetuate such upbringings without external factors to prevent them.

If we allowed Ghetsis to “decide for [himself] how to relate to Pokémon,” well, we know how that would go.

Besides Juniper, there is no one who N flat out denies. N does in fact open himself up to other ideas, at least in his own way. N actively invites the player to try to stop his plans because he can tell how much their Pokémon love them. N even shows Alder some semblance of respect after defeating him at the Pokémon League. “In order to forget the pain in your heart [from losing your Pokémon to sickness], you wandered Unova…” he says. “Who knows how long it’s been since you’ve had to fight with your full strength? I actually kind of like that about you, though.”

Alder, the supposedly open-minded, kind, and wise Champion, on the other hand, offers no such consideration towards N. “I lost. I should have been able to demonstrate the bond between me and my Pokémon,” Alder tells you after his spectacular loss to N. “That would have shown that brat the worthlessness of his outrageous dreams.” Calling N a “brat” while still bitter over his defeat is understandable, if not somewhat juvenile. Calling N’s dreams “worthless,” on the other hand, is taking matters a step too far.

N’s mentality essentially boils down to, “People always hurt their Pokémon, so there should be no more Trainers.” It’s easy to fixate on how his posited “solution” to the perceived problem is too extreme, and for good reason. But why does no one, not even Alder, try to meet him where he is? If someone were to say something along the lines of, “Parents always hurt their kids, so there should be no more parents,” it should be clear that the person is speaking from a place of personal trauma. Instead of running to defend the societal insistence that parenthood is an obligation, we should instead try to meet this person where they are, to ask them why they believe what they do, even if it means questioning our own beliefs. From there, we can all reach the healthier conclusion that some parents are wonderful, but some are absolutely not, so we should find the root cause of this and work to minimize it as much as possible.

But no main character in Black and White takes this approach with N or anyone in Team Plasma. In Castelia City, Burgh asks Ghetsis, “What you guys are doing… Aren’t you going to strengthen the bond between people and Pokémon even more?” According to A. S. Ferguson, “the purpose of the cave [in Plato’s allegory is] … to absorb the prisoners so that they are unaware of the [world] outside, and are, indeed, turned away from it.”14 It’s obvious how this applies to N’s upbringing, but it also applies to everyone outside of Team Plasma. The cave they’re in, shaped by the formulas of the Pokémon series, insist that people and Pokémon already have a perfect relationship, so questioning it just makes certain people more stubbornly dig in their heels.

But no main character in Black and White takes this approach with N or anyone in Team Plasma. In Castelia City, Burgh asks Ghetsis, “What you guys are doing… Aren’t you going to strengthen the bond between people and Pokémon even more?” According to A. S. Ferguson, “the purpose of the cave [in Plato’s allegory is] … to absorb the prisoners so that they are unaware of the [world] outside, and are, indeed, turned away from it.”14 It’s obvious how this applies to N’s upbringing, but it also applies to everyone outside of Team Plasma. The cave they’re in, shaped by the formulas of the Pokémon series, insist that people and Pokémon already have a perfect relationship, so questioning it just makes certain people more stubbornly dig in their heels.

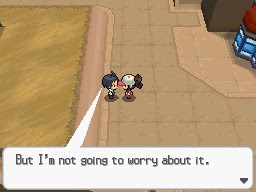

This isn’t to say that people must always change their opinions when hearing an alternative take. It’s entirely valid for someone to use Ghetsis’s rhetoric to reinforce their original belief that they will continue to be with Pokémon. But the only way to do so properly is by actually considering the other argument first. In Accumula Town, N introduces himself to the player and Cheren, and tells them that he’s interested in liberating Pokémon. Cheren’s response is to wait for N to leave, then say to the player, “Strange guy. But I’m not going to worry about it.”

Cheren believed in the Pokémon series creed that “Being a Trainer is good (and all Trainers should strive to become the Champion)” without question. Because of this, he dismissed N’s ideas without a second thought. Imagine if he, or anyone else, had simply asked N, “Why do you feel the way you do about Pokémon and Trainers?” Hearing N explain about his experience with abused Pokémon—and how Ghetsis brought them to him while he was locked away in some underground room that he was never allowed to leave—would have certainly changed the way they thought about N. They would have recognized N’s good intentions much faster and helped him deconstruct his old worldview. It may even have resulted in everyone focusing their efforts on thwarting Ghetsis much sooner.

As the YouTube channel Feeling Philosophical states in the video “Plato’s Theory of Forms,” “Obvious ideas are typically the assumptions that need to be questioned most, even though it might be against what is commonly believed. Plato goes against conventional wisdom [that the world we see is the real world] with his Theory of Forms, and so it is important for us to open up to these new ideas and try our best to understand them, so we don’t become too ideological and defensive over the beliefs that we currently have about the world.”15

N’s indoctrination at the hand of Ghetsis made it that much harder for him to question what he perceived as the truth about the world, but he at least made an effort by reaching out to the player. Every other character, on the other hand, had been indoctrinated by the formulas of the Pokémon world, and thus didn’t even think to try to understand N until after Ghetsis proclaimed his plan in N’s Castle. N must certainly take some responsibility for his actions despite the trauma at the root of them, but the characters around him are never that much more “in the right” even though—and precisely because—they fight to protect the unquestioned status quo.

Sometimes all it takes to understand someone is asking a simple question. As Socrates’s character says in Plato’s dialogue Gorgias, “I ask not in order to confute you, but as I was saying that the argument may proceed consecutively, and that we may not get the habit of anticipating and suspecting the meaning of one another’s words; I would have you develop your own views in your own way, whatever may be your hypothesis.”16

N asks questions throughout Black and White, not in incredulity like Ghetsis, but because he genuinely wants to understand. It starts in Accumula Town, with, “I can’t help wondering… Are Pokémon really happy [confined in Poké Balls]?” It grows into, “Do you really believe that Pokémon battles help us understand one another?” in Chargestone Cave. He even gives Juniper a chance to say her piece by asking, “What do you have to say for yourself?” instead of simply “anticipating and suspecting the meaning of [her] words.”17

As the pieces finally start to fall into place and he comes to understand the viewpoint you’ve hoped for him to see all along, he asks after his final defeat, “Two heroes living at the same time—one that pursues truth and one that pursues ideals. … Could they both be right?”

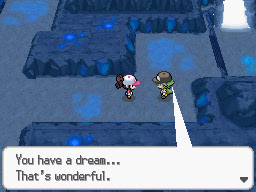

And, of course, in Chargestone Cave he asks the player, “Do you have a dream of your own?”

Alder spends much of Black and White asking Cheren what he would use his strength for after becoming Champion—in other words, what is his dream? It is N who asks this of the player, not so that he can confute you, but so that you can come to your own conclusion.

Alder spends much of Black and White asking Cheren what he would use his strength for after becoming Champion—in other words, what is his dream? It is N who asks this of the player, not so that he can confute you, but so that you can come to your own conclusion.

Even if that conclusion is the same as the belief you held beforehand, what’s most important is that the question was asked of you, and that you do your best to answer it. When a question is asked regarding your beliefs that you cannot answer, it means you haven’t given your beliefs enough thought. Questions shouldn’t be asked to try to convince others of your “correctness;” they should be asked because you want to learn, aligning with Plato’s view of the difference between the noble philosopher and the deceitful rhetorician as referenced in the chapter on Ghetsis.

N and Alder are both kings, but neither is a philosopher until Black and White come to a close. Alder thinks that with the death of his beloved partner came a revelation, but he doesn’t see Volcarona’s sun for what it is until he realizes that N’s “heart was truly inspired.” N’s journey across Unova is essentially him navigating his cave until he can find the exit. For both these kings, their journeys are crucial to their development, and, in line with their individuality, expressly one-of-a-kind.

The Champion is one-of-a-kind, yet it’s fairly typical for them to share their battle themes. The second generation’s Champion battle music is far more associated with Trainer Red than with Champion Lance. In Emerald, Steven’s battle theme from Ruby and Sapphire is given to Wallace while Steven himself borrows from Brendan and May. Palmer only started using the Frontier Brain track when the Battle Frontier was established in Platinum; before that, he used Cynthia’s own theme. With the sole exception of Blue, whose own unique track would go on to be remixed for the VGC championship bouts starting in none other than Black and White, it wasn’t until after Black and White that the Champion started getting a truly exclusive battle track. So while it may seem odd on the surface that Alder shares his battle theme with the Subway Bosses, it’s not only tradition, but quite fitting: all three characters are powerful post-game bosses with a theme that perfectly fits the stakes of their battles.

N, however, isn’t found in Black and White‘s post-game at all. Instead, he shares his battle theme only with himself. “Battle! (N)” is his battle theme from the start. Like “Prisoner to a Formula,” it’s off-putting, with a lot of staccato, erratic percussion, and a bold lower register that drives it forward. There’s also a constant feeling of tension caused by repeating tritones into fifths and fifths into tritones—unnatural, dissonant notes that never offer a sense of melodic resolution. Although he won’t reveal his connection to Team Plasma right away, N’s battle music already feels fitting for a villain. Even the series’s more ill-tempered rivals like Silver, Gladion, and Bede have an upbeat kick to their battle music compared to the ominous feeling behind N’s.

Compared to “The Pokémon Child, N,” which strips away the ornamentation of “Prisoner to a Formula,” N’s final battle theme, “Decisive Battle! (N),” adds to “Battle! (N).” Additional instruments and sound effects make the song even more intense than before, befitting for a final showdown. A ticking clock “express[es] the past and the future”18 that is so integral to Black and White‘s themes while also indicating the urgency behind this battle. A new pipe organ and chanting enhance the original song’s innate mysteriousness and imbue it with a sense of nobility indicative of N’s status as both a genius and a king.19 These are also musical elements that are typically reserved for and indicative of final battles, including the spectacularly iconic “Dancing Mad” of Final Fantasy VI, adding to the connotation of N’s battle as a finale even though Ghetsis serves as the true final battle of the games’ story.

Besides these thematic concepts, N’s battle music was also composed with math in mind. Using the keyboard’s middle C as “0,” composer Junichi Masuda uses chords and intervals of only prime numbers. Even the durations of notes and phrases are prime numbers20 to connect to N’s mathematical genius and preference of prime numbers that can’t be divided any further.

The connection between music and mathematics goes deeper than the ability to assign certain notes prime and composite values. N’s last name “Harmonia,” bestowed upon him by Ghetsis, blatantly originates from musical terminology. With the mathematical “N” and musical “Harmonia” together, the stage is set for Black and White‘s look at the overlap between math and music.

Pythagoras, a Greek philosopher who was one of Plato’s influences, is generally considered the “father of math and music.” He is typically thought of as the first person to attach math to music, and thus “founded” music theory as a concept.21 His many ideas would be used by Aristotle,22 contemporary of Plato, to form a curriculum that would be called the quadrivium in Medieval Europe. This long-standing curriculum included math—or numbers—and three other subjects in relation to math, one of which was music—or numbers in time.23

China was another country that “associated [music] with number symbolism.”24 The relevance of this fact is enhanced by how, according to Tresidder, “Yin or Yang qualities were allocated to the semitones of the earliest Chinese octave, music thus becoming a symbol of the vital duality holding together disparate things.”25 This ties music and its connection to math even more strongly into Black and White‘s themes.

The connection between math and music has continued well beyond the past and into the present, in which modern music theory posits that there are essentially “rules” regarding the order or “combination of notes,” and that those rules come from music’s innate ties to math.26 On the surface, this makes quite a bit of sense. A lot of music theory involves numeric patterns and mathematical operations. Ratios can even be used to express intervals, which are integral to a piece’s melody and harmony. As explained by YouTube channel Two Minute Music Theory, “The more simple the ratio, the more consonant the interval. Therefore, the more complex the ratio, the more dissonant the interval.” A perfect fifth is the simple ratio of 3:2, while a tritone can be expressed as a horrific ratio of 64:45,27 giving mathematical reasoning behind its unpleasant sound.

This should be perfect for someone like N. Formulas express even something like music, neatly compartmentalizing things into “right” or “wrong,” “works” or “doesn’t work,” “good” or “bad.” Still, the notion that music can be “right” or “wrong” is questionable. Individuals have their opinions on music they like and dislike, but that has no bearing on whether certain music is innately “good” or “bad.” For people who aren’t acquainted with music theory, the idea that music isn’t influenced by culture and is instead “universal” the way math is28 is just as, if not more unbelievable than the notion that Pokémon should be liberated from people.

It’s reasonable to say that there’s no “right” or “wrong” way to play or make music. Different cultures have their own kinds of music theory, with their own “rules,” their own “truths” and “ideals” for the way notes can be combined and ordered.29 And, personal preferences aside, they all sound good in their own ways—none is “better” than the other, none is more “right” than the other. There’s a time for the “rules” of western music theory, and there’s a time to break those rules. Even something like the “unpleasant” tritone can have its effective uses and make for fantastic music.

But while we can detach math from music, we can’t detach math from itself. Math is considered a “universal language.” In fact, it’s considered so universal that astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei is attributed with saying that “Mathematics is the alphabet with which God has written the universe.”30 This saying gives some extra zest to Ghetsis shortening N’s name into a variable, positing Ghetsis as a god writing his own universe with his own twisted form of mathematics.

For all us mortals, however, math is still considered universal. Certain words don’t have direct translations across different languages, and those that do may still posses cultural connotations that can never truly be conveyed by words alone. But one plus one is two in the United States just as much as it is in Japan or Brazil. Numbers are unchanged no matter where in the world you go. There’s no getting lost in translation.

It’s not just numbers and operations that are universal, either. Concepts, from the rudimentary to the advanced, similarly exist beyond the borders that would normally separate people, such as culture or class. One such basic concept is “natural numbers,” which is where N’s full first name, “Natural,” comes from.31 In fact, while a lowercase “n” is a common mathematical variable, an uppercase “N” is used in math to represent the set of natural numbers, those being positive integers, or the numbers we use to count things. These numbers are the ones that, in a general sense, make operations simple. One, a natural number, plus two, another natural number, is three, yet another natural number. Two times three is the natural number six, and so on. Their simplicity can even be considered “childlike,” or even reminiscent of childhood math, tying in with N’s childlike innocence and purity.

But just how universal is math, really? Even a concept as simple as natural numbers has a gray area: since most people begin counting from one, the non-negative integer zero isn’t always classified as a natural number. In addition to debatable definitions, there’s also framing to consider. No matter how “universal” “ten divided by five” is, you can’t just plop a worksheet in front of a student and expect them to complete it when the directions are in a language they don’t understand.32 And that’s not even getting into math’s infamous “word problems.” “Ten divided by five” becomes a lot less “universal” when written as, “If Team Plasma liberates ten Pokémon from five people, what’s the average number of Pokémon each person had?”

The reason why “word problems” like these exist is precisely because it’s important to frame math. Similar to how Alder tells Cheren that what he chooses to use his strength for is what’s important, what we use math for is far more important than the math itself. Whether it’s something of low to mid stakes, like using math to help with budgeting, or high stakes, like using math to create life-changing machines, it’s what you do with math that gives math its value. Sure, equations can be thought of as “right” or “wrong,” but what does it matter if “two times three is six” or if “x – 1 = 3 if x = 4?” None of that actually matters if it isn’t framed in some way. Two times three is six finally matters if I only have five dollars on me, so I can’t buy two three-dollar Poké Balls just yet.

The only way to frame things is for them to be touched by humans—humans whose perceptions and biases are clouded by all sorts of subconscious factors. And that’s actually a great thing, as long as we recognize that those biases are there. Our perception may be flawed in how we can be unconsciously influenced, but that is exactly how we come to have our own ideas. Our differing interpretations of an allegory’s metaphors and our opinions on the benefits and drawbacks of the world’s formulas make us unique. Because of that uniqueness, we can learn from each other and then better make our own dreams into a reality.

“I love Ferris wheels,” N nonchalantly informs you before boarding the Rondez-View Ferris Wheel in Nimbasa City. “They’re like collections of elegant formulas.” But that non-prime collection of formulas was brought together by civil engineer George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. The formulas could not create something like a Ferris wheel by themselves, and most people besides Ferris Jr. likely wouldn’t have even thought to combine those formulas together in the first place. It’s also notable that Ferris wheels have come to represent connecting people, especially in Japan where Black and White were developed, where Ferris wheels are frequently associated with dates. On top of that, Ferris wheels are made with many different formulas working together, not just a single equation separated from the rest.

Thinking of math or equations as purely black or white limits math’s true possibilities, just like how thinking of someone’s beliefs as either entirely right or wrong limits your understanding of them and limits your own potential to grow. Instead of thinking of math and its equations as either right or wrong, they’re better thought of as tools to determine the results of bringing together different ideas, with nothing beyond the “equals sign” besides infinite possibilities.

When there is something beyond the equals sign, such as the end result of the player’s victory in any Pokémon game, consider that there may in fact be multiple valid values for each variable. As mentioned previously, the most common “variables” in a Pokémon game are the Pokémon you choose for your party. And while there are some Pokémon that make beating the game much easier, it’s still possible, with the right levels and strategies, to complete almost any game with almost any Pokémon, with some players thriving on beating entire games with a single Pokémon the entire way through.

When there is something beyond the equals sign, such as the end result of the player’s victory in any Pokémon game, consider that there may in fact be multiple valid values for each variable. As mentioned previously, the most common “variables” in a Pokémon game are the Pokémon you choose for your party. And while there are some Pokémon that make beating the game much easier, it’s still possible, with the right levels and strategies, to complete almost any game with almost any Pokémon, with some players thriving on beating entire games with a single Pokémon the entire way through.

Math is hardly as universal as it seems on the surface. As Ph.D. and mathematics teacher Jay Wamsted says, “The only universal language is the one we make by doing the hard work of communicating with each other.”33 N’s thoughts on formulas may have been founded on the initial assumption that equations are “black or white,” but the true, ideal purpose of math lies in the ways humans can use it for different purposes. Just like “truths” and “ideals” or Yin and Yang, the “logic” of something like math and “emotion” that comes with human influence are actually inseparable. They are two sides of the same coin; you can’t have one without the other.

“Many ancient traditions,” Tresidder claims, “did not make a sharp distinction between feelings and thought. A person who ‘let the heart lead the head’ would once have seemed sensible rather than foolish.”34 The people of ancient Unova agreed with this concept, too, as statements such as “Have the heart of king” and “King acts with love” are written in the Abyssal Ruins, not statements like “King acts only based on logic.”

Chronologically, the Relic Castle was built after the Abyssal Ruins, and it takes much inspiration from Ancient Egypt. In Ancient Egypt it was thought that “‘The heart is the source of all knowledge’ and ‘What the arms do, where the legs take us, how all parts of the body move—all of this the heart ordains.'” In other words, functions we now associate with the brain were once “believed to be functions of the heart[.]”35 The heart isn’t just “The symbolic source of [emotions] but also of … truth and intelligence”36 and even willpower.37

It’s not unusual for concepts to change so thoroughly over time like this. But then we can’t help but ask, when were things “true?” Have they ever been “true,” and if not, will they ever be? Which interpretation of the heart versus the mind is “ideal?” How can we ever hope to know?

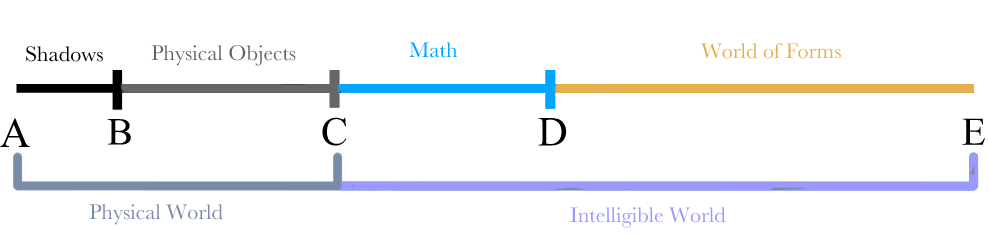

In Plato’s analogy of the divided line, Plato describes the world as if it were on a line divided into four unequal parts. The five points, A, B, C, D, and E, form line segments representing different “worlds.” Line CE represents the “intelligible world,” while AC represents the “visible” or “physical world.” Within the “physical world” is line BC, where “actual, physical things themselves sit;” and line AB, the mere shadows or reflections of the physical things and intelligible world that we perceive.38

The further right you go along the line, the more “true” the world. Line DE is where the ideal Forms exist, the truest essences of them all. Right before them is line CD, which represents “mathematical reasoning.”39 To the Ancient Greek philosophers, “the truths of mathematics are independent of our perceptions” or “of our mind.”40 As Plato would say, someone could be raised in their metaphorical cave to believe that “2 + 2 = 5,” but that is just wrong, period. The “truths of math” are absolute and unchanging.

Forms themselves are also meant to be unchanging, which is what allows them to represent the true and ideal nature of the things and concepts they represent. If Forms could change, then how could we even begin to define such lofty concepts as “goodness” or “justice?” If the thing that makes us all “human” isn’t consistent, then how can we even be sure that we are “human” at all?

To avoid a full-blown existential crisis, the question we should ask is whether Plato’s Forms are exactly as he described or not. Aristotle posits the Third Man Argument as an objection to the Theory of Forms. The Third Man Argument centers around the concept that Forms must have the property of the thing or concept they represent. In that case, there has to be another Form to tie together the first Form and the object or concept, and then another Form for them, and so on indefinitely.41

In other words, Forms are meant to “explain properties” such as “human-ness,” but, as YouTube channel TeacherOfPhilosophy describes, “nothing is explained because the explanation can never get started if behind every Form there’s another Form…and so on.”42

The Third Man Argument isn’t without its own imperfections, but it wouldn’t be philosophy without questions. What is perhaps even more important than the substance of the objection itself is the fact that Plato himself seriously considered it. In Plato’s dialogue Parmenides, Plato “assails his own theory of [Forms].” As renowned translator Benjamin Jowett explains in his introduction to his translation of the dialogue, “The arguments [Plato uses] are nearly, if not quite, those of Aristotle; they are the objections which naturally occur to a modern student of philosophy. Many persons will be surprised to find Plato criticizing the very conceptions which have been supposed in after ages to be peculiarly characteristic of him. How can he have placed himself so completely without them? How can he have ever persisted in them after seeing the fatal objections which might be urged against them?”43

The Third Man Argument isn’t without its own imperfections, but it wouldn’t be philosophy without questions. What is perhaps even more important than the substance of the objection itself is the fact that Plato himself seriously considered it. In Plato’s dialogue Parmenides, Plato “assails his own theory of [Forms].” As renowned translator Benjamin Jowett explains in his introduction to his translation of the dialogue, “The arguments [Plato uses] are nearly, if not quite, those of Aristotle; they are the objections which naturally occur to a modern student of philosophy. Many persons will be surprised to find Plato criticizing the very conceptions which have been supposed in after ages to be peculiarly characteristic of him. How can he have placed himself so completely without them? How can he have ever persisted in them after seeing the fatal objections which might be urged against them?”43

As TeacherOfPhilosophy explains, Plato may have eventually come to reject his own theory of Forms, or he may have thought there was a solution to the Third Man Argument. Either way, Plato was “definitely” “aware of the problem and knew it was worth thinking about.”44

Black and White are the Parmenides of Pokémon. Some fans may find it surprising to see Black and White “criticizing the very conceptions” which are meant to be “characteristic” of the series. How could catching and battling Pokémon possibly be unethical? Maybe the writers thought there was a “problem” with Pokémon‘s formulas and hoped to work out some sort of solution. But even if the conclusion that is reached turns out to be the same as the conclusion held before, it’s important to question our preconceived notions all the same, so that solution can truly be “worked out.” And there’s no better Pokémon games to do so than the ones so innately tied to Plato’s ideas.

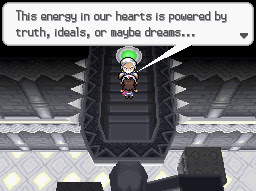

Both Alder and Drayden delve into some of Plato’s ideas, siding with Aristotle that Forms aren’t consistent. In the Celestial Tower, Alder explains that after his Pokémon died, he came to realize “that strength isn’t something that remains unchanged forever.” Drayden tells you in his Gym in the post-game that the “energy in our hearts is powered by truth, ideals, or maybe dreams” and “That probably changes with what you hope for in your life.”

Forms “change” because people change—not just collectively but individually. Factors that differentiate us, such as our height, age, personality, and beliefs, change within ourselves as time goes on. Who’s to say your “true, ideal self” exists at age 25 over 35 or even 45? And who’s to say that there’s an ideal or true Form of “blueberries” when some people prefer them tart while others prefer them sweet—and that preference itself can change, too?

Forms “change” because people change—not just collectively but individually. Factors that differentiate us, such as our height, age, personality, and beliefs, change within ourselves as time goes on. Who’s to say your “true, ideal self” exists at age 25 over 35 or even 45? And who’s to say that there’s an ideal or true Form of “blueberries” when some people prefer them tart while others prefer them sweet—and that preference itself can change, too?

N’s idea to separate people and Pokémon can be seen as analogous to Plato’s theory of Forms. Plato’s divided line shows the perfect truths and ideals existing in a realm completely separated from the physical world we inhabit. According to N, Pokémon can only become “perfect” once again if they are separated from humans. We can see where he gets this idea from thanks to Reshiram and Zekrom: they were once the same Pokémon—and perhaps even “perfect”—but then split apart into what they are today when the two hero brothers disagreed with each other. Perhaps keeping Pokémon separated from people would have kept the original legendary dragon as it was, but then we wouldn’t have gotten Reshiram and Zekrom, who are perfect in their own right, both equal to each other.

Just as N’s initial beliefs surrounding mathematics limited its possibilities, Plato’s theory of Forms has its limitations, too—limitations that Plato recognized and considered. Even Plato knew that he could be wrong, because the purpose of philosophy isn’t to be “right,” it’s to learn. Learning is a lifelong process, with questions leading us to slowly but surely uncover truths and ideals we never thought possible. And just as Plato can be wrong about his own beliefs, as long as he’s willing to give the opposition fair consideration, N’s incorrect assumptions and subsequent questioning of them are what allow him to change and become a better, more perfect, version of himself.

Appropriate to the concept that ideas and beliefs—truths and ideals—can change over time, many fans are finally starting to consider and even champion the possibility that N can in fact be a rival. Despite this, it’s still taking some time for people to open themselves to the idea that N can be a Champion. The justification dissenters opt for are generally tied to series traditions surrounding the Champion, and understandably so. Black and White question the series formulas while abiding by them. That abidance makes using past series traditions fair game when it comes to interpreting its characters and concepts.

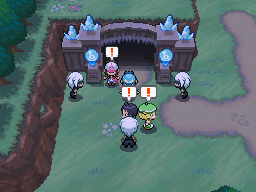

One such tradition involves the player’s induction into the Hall of Fame after defeating the Champion. The corresponding argument against N as a Champion is either that “N didn’t enter the Hall of Fame after defeating Alder” or that “When you beat N, you don’t get inducted into the Hall of Fame.” The latter is very easy to rebuke, as the final showdown was in N’s Castle rather than the Pokémon League proper, and it’s followed by a battle with Ghetsis. The “first clear” entry—which is lumped in with the Hall of Fame entries—in the PC is more indicative of how you fight both N and Ghetsis to literally clear the game. Whether N is a Champion or not, the battle against Ghetsis would always shape the status of the “Hall of Fame” entry.

The former argument is a bit more valid as a dissent, but it’s still worth pointing out that after N defeats Alder, he besieges the Pokémon League with his castle. We can’t deny that he doesn’t have the opportunity to enter the Hall of Fame properly. Still, it would be kind of sad if it was the case that you could defeat the Champion fair and square but if you somehow forgot to enter your information into the Hall of Fame, your victory doesn’t count.

“N declined the title” is another reason that gets repeated by dissenters often but actually has no foundation in the games, save for perhaps N calling himself “a Trainer who far outmatches the Champion.” The problem with this argument is that no one questions that the victor of a battle “outmatches” the loser. When the player defeats Blue in the first generation, it’s because they surpass him as a Trainer. When the player defeats Steven, Diantha, and even Cynthia, it’s not because they’re equal to them but stronger. The championship bout is meant to represent two Trainers fighting at their strongest, so when one person emerges the victor, they establish themselves as the stronger Trainer.

“N declined the title” is another reason that gets repeated by dissenters often but actually has no foundation in the games, save for perhaps N calling himself “a Trainer who far outmatches the Champion.” The problem with this argument is that no one questions that the victor of a battle “outmatches” the loser. When the player defeats Blue in the first generation, it’s because they surpass him as a Trainer. When the player defeats Steven, Diantha, and even Cynthia, it’s not because they’re equal to them but stronger. The championship bout is meant to represent two Trainers fighting at their strongest, so when one person emerges the victor, they establish themselves as the stronger Trainer.

Misunderstandings over N’s dialogue aside, it is true that N’s goal is to defeat Alder rather than to act as reigning Champion. N intends to have everyone release their Pokémon after his victory, so there isn’t much reason to undergo the formalities that come with the Champion title. What does it matter to N if he is considered a “Champion” when there will soon be no more Trainers and thus no more Champions?

This may seem to indicate that N is, in fact, not a Champion after all. But in actuality, N is indeed a Champion, at least in essence. Whether he has an official certificate granting him the title or not, N’s final battle fulfills the same role that the Champion battle traditionally fulfills, that being the one that signifies the end of the game specifically after obtaining all the Badges and defeating the Elite Four. Even if N is the Champion “only” symbolically, symbolism is a key element of storytelling that shouldn’t be overlooked. And, as explored in the dozens upon dozens of previous chapters, symbolism is used extensively in Black and White, making this interpretation as valid as any other.