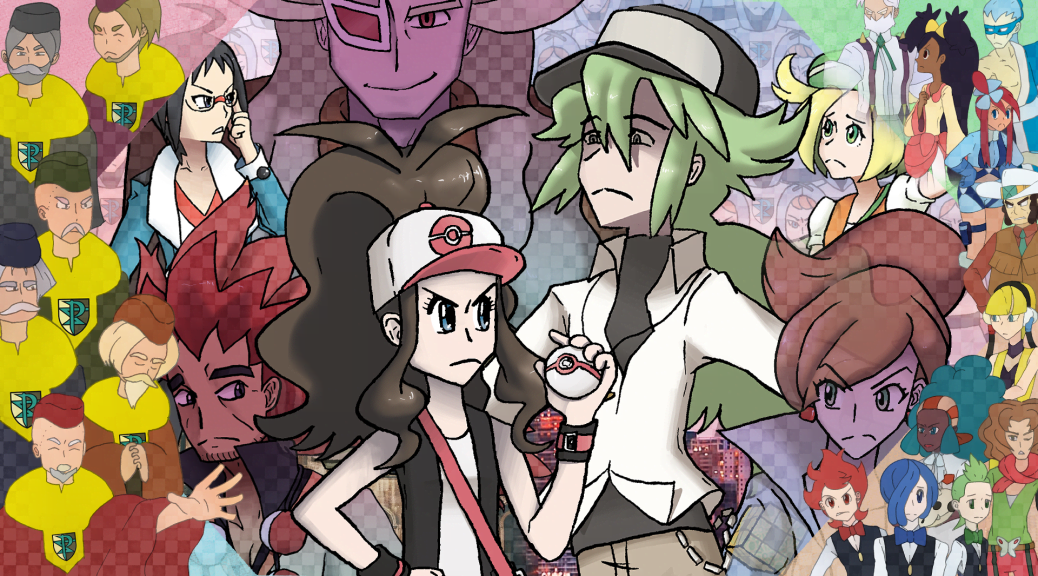

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Part III of our tribute to Pokémon Black and White focuses on each of the games’ many characters.

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Hilda and Hilbert | Juniper | Bianca | Cheren | The Gym Leaders | The Elite Four | Alder

Team Plasma Grunts | Concordia and Anthea | The Seven Sages | The Shadow Triad | Ghetsis | N

Concordia and Anthea

Fathers symbolically stand for “supreme authority” due to the patriarchal nature of the world’s societies.1 The father figures in Black and White hold similar authority, and massively influence their children or whomever fills that role for them. Ghetsis, markedly evil, grooms N for his own benefit. Bianca’s father stands in the way of her going on her journey, doing what he thinks is best for her safety. Cheren’s father figure comes in the form of Alder, authoritative and wise as Unova’s Champion, and the one who has Cheren question his preconceived notions and motivations. The transparent player character, lacking any sort of defined character arc, is pushed forward in the story by destiny, and has no direct father figure of their own.

But you, Cheren, and Bianca each have a mother.

No matter the stance—the state of existence—of their father, Cheren, Bianca, and the player all have a supportive mother who wants what is best for them. “My mom, Bianca’s mom, and your mom made a request to Professor Juniper,” according to Cheren. “They wanted us to go out and see the world.” And so Juniper delivered a set of three Pokémon to your home, and bestowed upon you all a Pokédex, the marker of a Trainer who may go out on an adventure of their own.

Mothers, literal givers of life, tend to stand for “the transmission of life” symbolically even within a patriarchal society,2 and this comes across through your mothers’ desire for you all to leave the home and explore. Rather than utilizing a “leaving the womb” metaphor, it’s far more appropriate to liken this to leaving the shelter of your metaphorical cave. By doing so, you learn and discover new things for yourself—although caves tend to be considered womb-like symbolically,3 so the comparison comes naturally. The choice to have each characters’ mother request they go on an adventure is deliberate with this symbolism in mind.

But where is N’s mother?

Concordia and Anthea are seen only twice throughout all of Black and White, with one of those times being the opening sequence, during N’s coronation. In N’s Castle, Anthea will heal your party, and both young ladies impart wisdom pertaining to N. They’re around N’s age—neither is likely his literal mother—but they fulfill maternal roles, supportive of not only N, but you as well, as evidenced by their restorative abilities and overall lack of hostility. Described as “the Goddess of Peace” and “Love” in Japanese, respectively, they continue to conjure connections to the theme of motherhood, just as male deities tend to be associated with fatherhood.4 Their titles, lost in the games’ English translation, also work in favor of Ghetsis’s grooming and ego. How many people can claim their childhood caretakers were literal goddesses? N being directly looked after by “goddesses” enhances his connection to god-given kinghood. And, of course, for these goddesses to be ruled by Ghetsis places him above them all—a man above the gods themselves.

Unlike the player and their friends, it is not N’s mother figures who allow him the opportunity to venture out into the world, but rather Ghetsis. And it’s not for N’s benefit, but only because Ghetsis’s plan must be put into motion. Concordia and Anthea are powerless at the mercy of Ghetsis, and their lack of story involvement is a result of this. Confined to N’s Castle from before the player even presses “Start,” they remain at “home” just as your own mothers do, with the only exception being your mother following you only as far as Route 2 to deliver the Running Shoes to you. Although the Pokémon main series notably lacks literal fathers, especially for the player character, the mother figures aren’t any more relevant. It’s ultimately both sweet and humbling that your literal mothers got together to plan for your journey’s beginning—sweet in that they took direct action for your benefit, and humbling in that they had the opportunity to request a Pokémon from Juniper at all.

Not everyone has such opportunities, such connections, at their disposal.

Knowing the capabilities of Ghetsis and his shadows, it’s likely Concordia and Anthea were unable to do much more than what they were told—that is, to care for N as Ghetsis demanded. Their dialogue implies genuine concern for N; much like your own mothers in regards to you, Concordia and Anthea want what’s best for N. But because of the differences in your circumstances, they are far more limited in supporting him compared to your mothers.

This becomes most clear when exploring the concept of a home. Just as trees metaphorically stand for creation,5 reflecting the professor’s critical role in allowing your Pokémon journey to begin, homes are “the symbol for the center of existence for the human race.”6 You need the professor to give you a first partner Pokémon and Pokédex to begin your adventures, but you always begin within your own home. Even N begins the game within his “home,” as evidenced by the opening animation of his coronation, that Concordia and Anthea preside over, in his castle.

Homes are also inherently more maternal than fatherly,7 reflective of the womb-like cave: the home offers a sense of security, a refuge you wish to return to. Naturally, your mothers in each game tell you that you can come home whenever you want, or when things get too difficult and you just want a break. But do you ever return home?

The only game in which it’s practical to return home is Gold, Silver, Crystal, and their remakes, simply because your mother can save your money and you may want to retrieve some from her. Otherwise, most players never return back to their home town once they’ve set off—it’s simply impractical. In fact, in the aforementioned games, visiting canon player character Red’s house in Kanto allows you to meet his mother, who confirms that even he, as an established character, also never returns home. “Red’s been away. He hasn’t called either, so I have no idea where he is or what he’s been doing,” she explains. “They say no news is good news, but I do worry about him.”

So when does the player return home? The only time they’re forced back is after beating the game: after defeating the Champion and watching the credits, the player finds themselves in their room. It is understandable, then, that N makes a prompt return home after defeating Alder. And although he doesn’t respawn in his home after claiming the title of Champion, he does spawn the place he calls home around the league.

Considering all they’ve been through, however, Concordia and Anthea surely do not want N to return home. Home is supposed to be a comforting place. “Home is where the heart is,” as the saying goes, but what if that home is the place where you’re considered a freak without a human heart? Anthea describes N’s upbringing in the castle as “painful,” which may in some ways be underselling it.

Unlike the player’s return home each time they beat the game, which is met by celebration from their mother and the beginning of their “post-game” excursion, N’s return home is far rockier. He is defeated by the player, berated by Ghetsis, and forced to confront his own beliefs more than he ever has before. Thankfully, however, this homecoming culminates in the beginning of N’s own “post-game” journey—or perhaps the start of his true, initial Pokémon adventure—as he bids you farewell and takes off on the back of his trusty dragon companion.

After putting a stop to Team Plasma, you respawn in your own home. As you leave your room, you find your mother downstairs has an exact double—two maternal figures for a brief moment, before one reveals themselves to be Looker.

But no visits home last very long in the Pokémon world. You’re given another task—to find the remaining Seven Sages—and you set off once again.