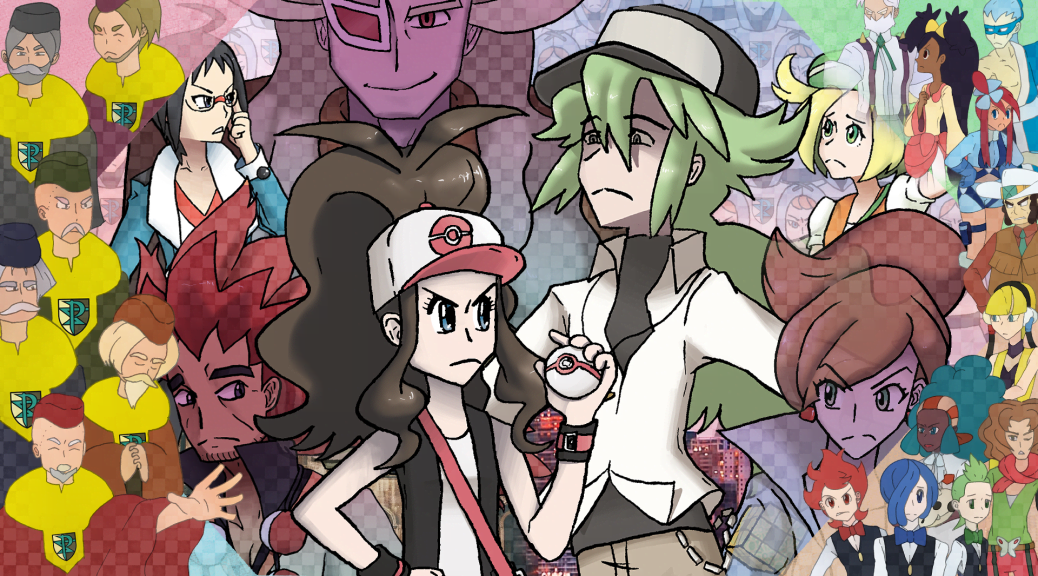

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Part III of our tribute to Pokémon Black and White focuses on each of the games’ many characters.

Part III: The Cast of Unova

Hilda and Hilbert | Juniper | Bianca | Cheren | The Gym Leaders | The Elite Four | Alder

Team Plasma Grunts | Concordia and Anthea | The Seven Sages | The Shadow Triad | Ghetsis | N

Ghetsis

The Pokémon world is perfect. Conflicts are minimal, and those that do arise are neatly wrapped up with good prevailing over the clear evil. It’s this very perfection that causes Team Plasma to fail, as N realizes that the formulas the world is built upon do, in fact, work. People and Pokémon can, in fact, live together in harmony.

The Pokémon world is nearly dreamlike in its utopic state—but just as black cannot exist without white, dreams cannot exist without nightmares.

Black and White insists that there are always two sides to every argument, and that no one side “has all the answers,” according to Alder. But even this ideal isn’t entirely true. While no single viewpoint can be entirely correct, there absolutely are some perspectives that are entirely wrong. Some don’t mean to be, but others are by intention. Both are dangerous because of how the people who believe them think them to be true.

Ghetsis Harmonia is the mastermind behind Team Plasma, and everything about him is duplicitous. Black and White‘s portrayal of dichotomy culminates with Ghetsis, whose entire being exudes the negative qualities of symbols that have otherwise been used positively throughout the games. This begins in the Dream Yard, when a Musharna comes to the aid of a Munna attacked by Team Plasma Grunts. Musharna sets upon the grunts an illusion of an enraged Ghetsis—but even in this state, Ghetsis appears calm and composed, using deliberate choices of words to instill fear. The grunts briskly flee, terrified of this vision of Ghetsis who’s different than “when he is trying to gather people… Or trying to trick them with speeches.” After this, Fennel arrives on the scene to explain that Musharna can make dreams into reality, although the vision of Ghetsis players just witnessed is far more akin to a nightmare.

Even more nightmarish is Ghetsis’s idea of perfection. The concept has been established by Black and White‘s repeated use of the hexagon and the perfect number six. N applies it not to himself but to Pokémon: he thinks Pokémon are “perfect beings” who should be freed. On the other side of this spectrum lies Ghetsis, who believes the only things of perfection are himself and a world completely under his control, as he decrees incredulously after you defeat him, “I’m absolutely perfect! I AM PERFECTION! I am the perfect ruler of a perfect new world!”

This entirely self-centered perspective on perfection isn’t the only way Ghetsis warps the concept, however. He twists the normally harmonious number six into “the number of the Beast,” the number of the Devil himself, 666.1 He does this through the control of six other sages, six youths he brought into Team Plasma for his own benefit—the Shadow Triad, Concordia, Anthea, and N—and a team of six Pokémon he can use if, somehow, his “perfect” plan goes awry.

Similarly demonic is Ghetsis’s hand symbolism discussed in Part II. While N utilizes positive hand symbolism, Ghetsis’s is entirely negative, etymologically sinister as his exclusive use of the left hand enforces his evil character. The importance of the right hand was once so great that, according to Tresidder, “one Celtic ruler was deposed after he lost his right hand in battle,”2 and, appropriately, Ghetsis claims within Team Plasma’s castle that he “couldn’t become the hero and obtain the legendary Pokémon [him]self,” which is what led him to “prepare [N] for that purpose.” Rather than become the king himself, Ghetsis became the—in his eyes—perfect, god-like figure who bestowed N with his title—and N, newly crowned in the opening sequence, stands to Ghetsis’s right. This draws further parallels to Ghetsis’s god complex, as it is said “Christ sits on the right hand of God,” and God “dispenses mercy with the right [hand and] justice with the left.”3 But Ghetsis can’t dispense any sort of mercy as he lacks a right hand altogether. And as is made abundantly clear, Ghetsis’s idea of “justice” is highly warped and benefits only himself.

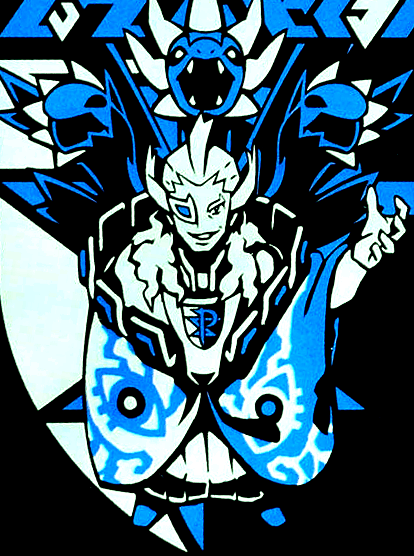

We can see even more of this god complex mentality through Ghetsis’s visual design. Wearing robes immediately conjures ideas of a priest or pope—the kind of religious figure with the god-given authority to crown the divinely sanctioned king4 or declare the start of a crusade. Yet the design upon his robes is anything but heavenly: half yellow and half blue, sporting two large eyes with horrifically long eyelashes and markings underneath. Even more striking is how in the midst of this yellow and blue the eyes have what appear to be irises of pure red.

Again, Ghetsis takes on colors and imagery that are filled with both positive and negative meanings. The positives are what Ghetsis wants others to perceive him as—and what he believes himself to be—while the negatives are what players discover is his true self. The right side of his robes are predominantly yellow, which can normally encompass ideas pertaining to rulership—what Ghetsis truly desires—as it matches the color of the powerful sun: wisdom, good advice,5 illumination, rulership, divinity, and truth. It also, as the color of gold, stands for perfection, which naturally made the metal the go-to “for sacred objects or for sanctified kings.”6 It “was the color of royalty” in places such as China,7 and is especially meaningful in Buddhist countries “through its link with the saffron robes of monks,”8 tying in with the themes surrounding royalty and the inherent minute religious concepts that accompany them. But yellow also represents treachery, deceit, and betrayal.9

On the left, Ghetsis’s robes are a deep blue. Taking the importance of blue from the grunts’ uniforms a step further, this heavenly color is usually worn by the Virgin Mary and Christ Himself in imagery.10 While Ghetsis continues to enforce his god complex through color symbolism, those who know better see the blue of secrecy, cold cunning, and impending darkness11 on his person. Even more strikingly in line with Ghetsis’s duplicity is how he wears the yellow robes of Judas12 directly beside the blue robes of Christ.13

The eyes on Ghetsis’s robe have six eyelashes each, continuing to emphasize the ever-important number. Eyes themselves represent many things, including “the sun, the all-seeing eye of God, and eternal watchfulness,”14 further pushing Ghetsis’s horrifying mentality.It also offers a glimpse into the true extent of his power: with how much he knows and how much he controls throughout Black and White, “eternal watchfulness” or omniscience15 is actually frighteningly accurate for him. Of course, Ghetsis’s use of his all-seeing eye—singular, as his actual right eye is entirely obscured by a visor—is tinted a far more negative hue thanks to his actions. Eyes are considered to have the power to curse, such as through the belief of the “evil eye,”16 or the ability to inflict bad luck onto others with a malicious glance.

These negative associations come across even more pronouncedly in the striking red irises of both the robe’s eyes and Ghetsis’s own eye: eyes, considered “windows to the soul,” can sometimes have a lot to say about the person’s true self,17 and red is a color with a lot of divisive meanings. Instead of its more positive associations, Ghetsis’s red is far more aligned with political revolution and war,18 both directly tying in with Team Plasma’s outward goals and direct parallels to the Crusaders. Red also stands for strength19 or power,20 something Ghetsis already has to an extent, and seeks more of. The hand, as a major exactor of action, also stands for both “temporal and spiritual” power, strength, and even domination,21 and it’s important to reiterate that both Ghetsis’s hand and red eye are functional only on his left side, indicating that he seeks power for evil ends. Red can also stand for aggression and acts of violence,22 and in some cultures is simply indicative of evil itself.23 Red is also highly visible, and as such is used to indicate danger,24 with “dangerous” being a highly apt way to describe Ghetsis.

Yellow is the most visible color to the human eye, and thus is also used internationally for warning signs.25 In fact, the colors that most draw our attention are the primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—and green,26 all of which are major components of Ghetsis’s visual design. The final color, green, is used on Ghetsis as a direct contrast to N. While N’s hair is a bright, lively green, the color of life and youth,27 Ghetsis’s is a pale, putrid green, symbolic of illness and death.28 And while both characters encompass green’s attribution to otherworldliness29 in some way, again N’s is far more positive—with his ability to speak to Pokémon—while Ghetsis’s is far more negative—his inhumane level of knowledge and subsequent control over others, and the inhumane lengths he’s willing to go to to see his goals achieved.

More specifically, Ghetsis is downright demonic. The color of both his eye and hair have been used to represent the Devil—sometimes with red skin, the color of hellfire,30 other times with green, the color of death and decay.31 Ghetsis himself tops it all off with his hair stylings: unlike N, whose hair falls down beside his ears, Ghetsis’s hair curls up, giving his silhouette the appearance of horns, imagery that became representative of Satan after Christianity “turned against pagan worship.”32

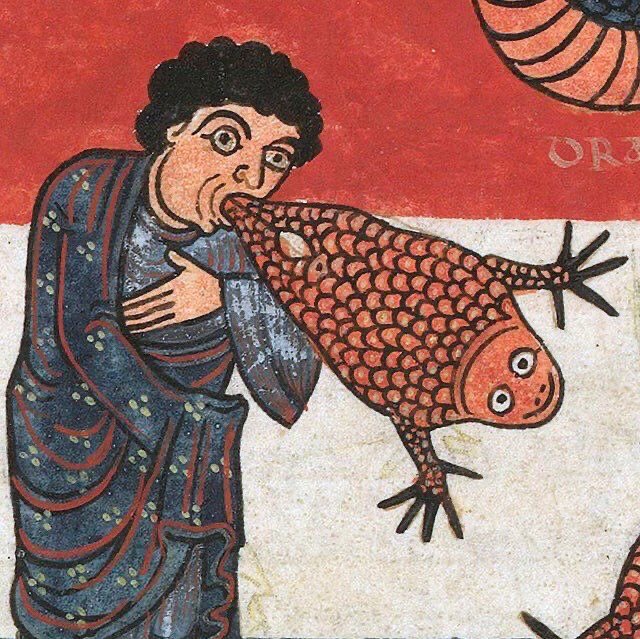

Further influences from Christianity can be seen in classic Medieval art, such as the following illustration depicting a “false prophet” with his right hand hidden away in his robes just like Ghetsis. But the final nail in Ghetsis’s Cofagrigus of demonic imagery comes from the toad-like creature escaping the false prophet’s mouth;33 in other words, Ghetsis’s very choice of Pokémon contributes to his demonic depiction. He starts off with Cofagrigus, the literal Coffin Pokémon whose association with death needs no introduction. Bisharp, the Sword Blade Pokémon, has a clear parallel to the sword as featured on the Team Plasma logo, a weapon representative of death34 due to its natural connection to war.35 In the Pokédex, Bisharp is described as a leader of “a group of Pawniard” in both Black and White, and in White, Pawniard is listed as always “fight[ing] at Bisharp’s command.” This naturally parallels Ghetsis’s own views of himself as a leader meant to control everyone else as his literal pawns. The evolutionary line’s names also bear a fascinating relation to Ghetsis. In Japanese, Pawniard’s name carries the brunt of the board game references, with the koma in Komatana being the Japanese word for “board game piece.” In English, the chess references are far more blatant, applying to both evolutions. And interestingly, they don’t culminate with the king. Instead, the leader is a “bishop,” styled after a high priest or pope just like Ghetsis.

You don’t need to read Bouffalant’s Pokédex entires or classification to know it’s a large bovine. Animals such as the buffalo or bison are important symbols in both North America and Asia. In both areas, they stand as “a symbol of formidable power.” To the Native Americans of the Great Plains, they symbolized “the strength of the whirlwind,” and their herds were described as “thundering,” with thunder itself representative of divine might. On the other hand, their “high status … made it a sacrificial animal” in India and Southeast Asia.36 These two differing interpretations encompass both Ghetsis’s god complex and the ease with which he would sacrifice others for his own gain.

Another party member that may seem rather unassuming at first glance is Seismitoad. The toad, however, has incredibly negative associations, partly due to their unflattering appearance and partly due to the toxins they release.37 As a result, they’re usually considered to be evil38 or demonic; when they’re not working with witches, they’re thought to be among those tormenting the damned in hell.39 Eelektross is also based on an unsavory animal, one associated with dishonesty and trickiness. The eel, who conjured its own modern metaphor of being slippery,40 is another good example representing Ghetsis’s deviousness, in addition to how he’s literally “slippery” at the end of the game, escaping Cheren and Alder’s grasp with the help of the Shadow Triad. Additionally, Eelektross is a rare instance of a Pokémon with no weaknesses thanks to the combination of its Electric typing and Levitate Ability, a clever parallel to the state Ghetsis wishes for himself.

Finally, Ghetsis has his iconic ace Pokémon: Hydreigon. This Dark-type, sinister Pokémon—unabashedly classified as the “Brutal Pokémon”—is Ghetsis’s own dragon. Unlike Reshiram and Zekrom, who encompass the positive, predominantly East Asian, view of dragons,41 Ghetsis’s Hydreigon embodies their negative, demonic symbolic qualities, which primarily came about due to Christian influence.42 This is because dragons are, according to Biedermann, “exaggerated versions of the snake and its … fear-inducing … menace.”43 The snake is particularly egregious in Christian symbolism due to the serpent that appears in the Garden of Eden. The aforementioned white of Team Plasma’s uniform can be seen as representing a return to Eden’s perfect state,44 and the reason why it must be returned to is because the serpent deceived Eve. As Biedermann notes, the serpent targeted Eve because she was “more susceptible,” and would “listen to [him], because [she would] listen to anyone.”45 Ghetsis’s character removes the uncouth gender-based stereotypes from the situation and instead focuses purely on the matter of deceit: as he makes clear throughout the game, Ghetsis’s success hinges on his ability to convince the masses to agree with him. Although he begins by claiming Team Plasma “only free[s] Pokémon from wicked people,” it’s not long before he becomes complacent in showing you his true colors, and begins referring to “foolish people” specifically—foolish in that they “know nothing,” as he says in N’s Castle. As the serpent would say, those who are “more susceptible” and would “listen to anyone”46 so long as they’re presented with a good-sounding argument.

Before Christianity, snakes were more considered a “symbol of primeval life force, sometimes an image of the creator divinity itself.” This can be seen through the iconic “ouroboros,” a snake eating its own tail.47 But Ghetsis’s Hydreigon, as yet another decidedly negative approach on the positive associations Black and White would otherwise portray, isn’t an ideal “creator divinity,” even though Ghetsis sees himself as one. While the ouroboros consuming itself symbolizes “divine self-sufficiency,”48 Hydreigon isn’t self-sufficient in the slightest. Its White Version Pokédex entry claims “They use all three heads to consume and destroy everything,” inflicting harm onto others rather than acting as a creative, positive force. Even its Black Version Pokédex entry draws specific attention to “its six wings,” once again placing emphasis on its demonic qualities rather than the positive qualities the snake may rarely have.

Although the snake and dragon are oftentimes synonymous in myth and legend,49 which carries over to the significance of Ghetsis’s Hydreigon, there’s also symbolism particular to the dragon that stems from the negativity surrounding the snake. “Adversarial evil” is a good descriptor of Ghetsis, and that’s precisely what dragons came to stand for in Western mythos. As saints took to vanquishing dragons, which began to symbolize Satan himself,50 they took on associations with fire, including an ability to breathe fire,51 which isn’t part of their East Asian portrayal. To enforce this, Ghetsis’s serpent-like Eelektross’s coverage move Flamethrower takes on a more intentional meaning, and Hydreigon one-ups it by having the improved Fire Blast at its disposal.

To defeat this violent fire-breathing dragon, the world needs a hero, one with the might and discipline of a king.52 Both the player and N have the strength needed to enlist the aid of one of the legendary dragons, something that is consistently emphasized as a heroic attribute throughout Black and White. But when on the topic of Ghetsis, we have to shift our perspective on heroism: one mark of a king or hero is to slay a dragon—the evil versions depicted in fairy tales or religious myth53—and the player turns out to be just the person who can slay Ghetsis’s Hydreigon.

The dragons that must be slain can usually be found guarding treasure in caves, towers, or castles, all of which have been used as important landmarks across Unova, from the Chargestone Cave and Plato’s allegory, to the Dragonspiral Tower that literally hosts a dragon atop it, to N’s Castle where the game draws to a close with Reshiram, Zekrom, and Hydreigon all converging. And a castle, with its strong, protective walls, finds itself draped around Ghetsis’s neck, at once fortifying him and subtly referencing him as the “center” of the castle—the true king of the castle, the real ruler of Team Plasma.

But a large, imposing castle needs broad shoulders to rest upon. The smallest visual touch Ghetsis uses is just how big he is: Ghetsis’s sprite makes the most of its allowed space with his huge robes. While other character sprites taper in and out in areas to indicate necks and waists, Ghetsis’s sprite has very little negative space, making him appear larger than everyone else. His size is confirmed in later multimedia adaptations, having him tower over others in animations and spin-off games, but even in the confines of Black and White, where the sprites of human characters are all the same in dimension, Ghetsis manages to seem bigger than the rest, making him all the more imposing and menacing. And his wide sprite isn’t just for show. He’s always the one to push others aside when no one’s watching, such as when leaving you, Cheren, and Alder behind at Relic Castle, or when he brazenly invades your personal bubble outside of N’s throne room. Although he’s more than happy to verbally manipulate others to do the heavy lifting for him, Ghetsis is a man of action, fully in control of his agency. He is willing to use physical force—himself—when necessary.

When Ghetsis takes matters into his own hand, usurping N’s position as the final boss battle of the game, the emotions that come along with it aren’t always surprise. But should they be? It’s often held that Ghetsis’s supposed “big reveal” as “the bad guy” isn’t surprising enough—in other words, that he’s a poorly executed “twist villain.” But is he really a “twist villain?” To answer that, we need to talk about story structure.

The most effective and time-tested story structure is the “three act structure.” Like it says on the tin, this divides stories of any kind into three parts or “acts,” even if they’re not plays with individual acts, and even if it’s a play with more or fewer than three acts total. We know the three act structure is effective because nearly everyone insists that a story has a “beginning, middle, and end;” however, for more in-depth purposes, that terminology needs some elaboration.

Instead of calling the three acts the “beginning, middle, and end,” some people may call them the “setup, confrontation or rising action, and resolution.” But even that may be a bit too vague. What is being set up in the first act? It’s not always exposition, because too much “info-dumping” can come across as overwhelming, boring, or sometimes even insulting, as if the writer can’t trust the reader to follow along with the story unless they hold their hand and over-explain things that should be ordinary to the primary cast. What the first act should be setting up is the author’s authority: their ability to tell stories well, to trust their audience to follow along, and to set up the main ideas for the second and third acts.54 In Black and White, this is achieved through timely introduction of the main cast: unlike in other Pokémon games, such as Sun and Moon, which waits until the time surrounding the halfway point of the game to introduce supposedly important characters such as Gladion and Guzma, Black and White introduce Cheren, Bianca, N, and Ghetsis before players reach Route 2.

Team Plasma’s goal is firmly established at this point, too: Pokémon should be liberated. Or should they? Although N approaches you after Ghetsis’s speech and appears genuine in his convictions, the speech in question is given over a music track that replaces Accumula Town’s normally upbeat theme with one that is creepy, low, and unsettling. Without stating it outright just yet, the writing and music join to give players the chance to wonder if there could be something about Ghetsis that isn’t quite so genuine. Even the visuals join in: attentive players will register Ghetsis’s disconcerting design and the almost disturbing appearance of the indistinct, hooded grunts behind him, leaving a questionable impression of Ghetsis’s character and the nature of Team Plasma. To top it all off, this also establishes one of Black and White‘s major themes: dichotomy. By planting the seeds of doubt surrounding Ghetsis’s true intentions, players know to expect more writing in line with this theme later down the line.

Black and White‘s first act respects the player’s ability to think for themselves while also setting up the characters and themes that will permeate the second and third acts. Mechanically, the first act also includes all of the games’ seamless tutorials, from Striaton City’s monkey business to learning how to use the C-Gear. All the while, the main characters we’ve been introduced to are involved in purposeful scenes against Team Plasma that continue to establish their motives. This means that when moving into the second act, it’s not so much the action that’s rising as it is the tension.55 Tension builds as additional characters, such as Alder and the Gym Leaders, are brought into the mix, and N reveals himself to be the king of Team Plasma, inviting you to challenge him at the Pokémon League. And although the primary conflict exists between the protagonist and N, Ghetsis makes sure to stay involved in ways that escalate alongside the story’s tension. Each time he appears, his words and actions are more severe than the time before, adding further credence to the player’s suspicion that Ghetsis isn’t being truthful when he says he wants Pokémon to be liberated for their benefit.

In Castelia City, Ghetsis details the founding of the Unova region in an attempt to convince his audience that Team Plasma’s plan is in line with Unova’s very formation. Here, he actually has a slip of the tongue that no one seems to catch: “If we can win people’s hearts and minds, we can easily create the world that I—I mean, Team Plasma—desires!” On Tubeline Bridge, after N has joined forces with his legendary dragon, Ghetsis starts his speech to the player as he usually would, including the slip-up, “The liberation of Pokémon of which I… Of which Team Plasma speaks is the separation of Pokémon from foolish people!”

But he continues, and here tells the player—and only the player—that he groomed N for the sake of his plan literally “from [N’s] infancy.” It’s also here that he outright states his sinister scheme to the player: “All Trainers will become helpless to resist [Team Plasma]! We alone will be able to use Pokémon!”

By the time the player gets to N’s castle, they have been made privy to Ghetsis’s true intentions, so when he once again corrects himself—“We can bring into being the world that I—no, that Team Plasma—desires…”—it comes across as disrespectful, a complete disregard for the player’s intelligence. Ghetsis continues to look down upon the player as incompetent and incapable, which is reinforced by his earlier dialogue; after all, it would have been safer for Ghetsis to not appear before you on Tubeline Bridge at all, but he has always thought so highly of himself and lowly of you that he doesn’t consider you a threat even if you know the truth behind his schemes. Ghetsis being the “true villain” of Black and White isn’t meant to be surprising at all—in fact, the entire story builds up to it.

It’s precisely because it’s made clear that Ghetsis is “the real villain” that players can grow to loathe him throughout the game and appreciate his character as the villain that he is. And when the battle against him finally arrives at the very end of the game, it—and his subsequent defeat—is all the more satisfying for it. Jaw-clenching scenes like Ghetsis toying with Burgh in Castelia City, or threatening Clay on his own home turf, or mocking Alder and his deceased Pokémon in Relic Castle, are key pieces of Black and White‘s storyline. They pit characters with opposing motives against each other, having them develop in the face of adversity, all while escalating the story’s tension overall. This also heightens player investment. Because players get the chance to care about Ghetsis as a villain, they can wonder, what will he do next? Just how far can or will he take his selfish motives? How low is he willing to stoop to see his goals achieved?

And these questions are all answered in the story’s third and final act, the part of the story when it seems like things couldn’t possibly get any more tense… and yet it does.56 When you make it to the peak of the Pokémon League, N has defeated Alder. Can it possibly get any worse? Yes, actually, it can: Team Plasma’s castle emerges from the earth below to swallow up the Pokémon League. Can things possibly get worse than this? Actually, yes, as you make your way into the castle to try to stop N, six of the Seven Sages attempt to block your path.

Here begin the “twists” that audiences like to experience. But rather than call them a “twist,” which doesn’t explain what about the event makes it successful, it’s better to call them “the inexorable surprise: inexorable because it had to happen, surprise because no one saw it coming in this way.”57 The moment when the sages are blocking your way forward is so drenched in tension that it’s only natural to not come up with a solution on the spot. But once the music shifts and the Gym Leaders file in, it all makes sense: of course it had to be the Gym Leaders who stepped in to help you out. They’re the ones who have been helping the protagonist and their friends stand against Team Plasma throughout the game. And like the best kind of “twist,” it gives new meaning to older clues, proving the moment had been skillfully foreshadowed rather than randomly tossed in. The most notable of these moments belongs to Gorm’s remark in the Pinwheel Forest: “Even though you are Gym Leaders, we will not tolerate any further obstruction from you. In any case, we will settle this someday.”

But this is not the primary inexorable surprise of Black and White; after all, the primary conflict does not lie with the sages. The primary antagonist to the player’s protagonist is, and always has been… not Ghetsis, but N.

Once the sages are occupied, tension still looms as the player makes their way to the throne room and the final showdown with N. From here until that fated moment, there’s no way things can get worse, right? After all, it’s practically guaranteed that the legendary dragon will join you when the time is right. But then a member of the Shadow Triad appears before you and directs you towards N’s room, where the games’ ultimate inexorable surprise awaits.

When Ghetsis told you he groomed N, he meant it in one of the most horrific ways possible. Holed up in a windowless room, trapped with only abused and feral Pokémon, N was tortured for the vast majority of his life. Especially attentive players will also notice that this “twist” may also recontextualize the opening animation of N as a smiling, innocent child in a lush forest surrounded by happy Pokémon. Now there’s the implication that Ghetsis kidnapped N from this place, for the sole purpose of bringing him to this room and raising him as his puppet.

Black and White‘s big “twist” isn’t that Ghetsis was “the real bad guy all along;” the “twist” is his depravity, his complete disregard for life that isn’t his own, the lengths he’s willing to go to to see his unjust plan unleashed. How many years he’s willing to wait, how much he’s capable of planning, and how many lives he’s willing to ruin, all while directly destroying the life of a child to the point where his opinion is nearly impossible to sway—the child who ends up becoming the player’s main rival. The player’s connection to N makes Ghetsis’s treatment of him hit harder than his ambition to rule an entire region. Additionally, Black and White‘s inexorable surprise brilliantly serves as a twist for both Ghetsis and N: while illustrating the extent of Ghetsis’s inhumanity—aligning with his demonic themes—it also portrays the extent of N’s manipulation. Just as Ghetsis is inseparable from N due to the circumstances of his upbringing, N’s room delivers both N’s and Ghetsis’s “twist,” two successful surprises that are directly connected.

And the reason why Ghetsis’s “twist” is successful is precisely because players are keyed in to his true nature from the very beginning. Players can enjoy his character as the villain that he is while they play, and when the real twist does arrive, it meshes organically with the rest of the story. The reason why it meshes is because Ghetsis’s motives are clear and consistent, and his actions—and even the twist—align with them.

It’s strong motives that make a villain memorable, but “strong” doesn’t always have to equate to “complex.” It’s consistency that’s key. In stories, every detail matters. Every word written or facial expression animated is intentionally included by someone on the development team. Whatever a character does, it should be in line with a motive of some sort. Some motives are short-term—such as Ghetsis appearing before you, Cheren, and Alder beneath the Relic Castle to try to convince you that your search for the missing stone has been in vain, and to try to break Alder’s spirit. Others are long-term—such as Ghetsis’s manipulation of N, gathering of the sages, and building of the castle. Each action a character takes should be in line with their motives, and a “twist” villain who remains entirely incognito until the third act will have taken no actions that align with their motives. These are the characters who exist to “trick” the audience rather than the cast. But as a result, the story’s “twist” feels so contrived that it knocks the audience right out of their immersion, and the villain ends up being entirely forgettable, as poked fun of in the following comedy sketch by YouTuber and voice actor SungWon Cho.58

Instead, the villain should be taking actions that align with their motives. It allows the audience to piece together their true intentions, just like they can with Ghetsis. Coherency strengthens storytelling, it doesn’t weaken it. What’s critical to consider is that the audience isn’t actually a part of the story, so the villain shouldn’t be attempting to trick them at all, since they technically don’t exist. This gets a little tricky in video games, when the player takes control of any given character, and especially games that feature a silent protagonist literally meant to be an avatar for the player, such as in the mainline Pokémon titles. But even this is something Black and White have intelligently accounted for: Ghetsis not only explains his plan to the protagonist to display his arrogance and escalate the story’s tension, but to accommodate for the unique needs of the narrative. Ghetsis is able to trick the cast while allowing the player to piece things together, and in order for there to not be a disconnect between the player and the character they play as, Ghetsis tells the protagonist his plan specifically when it benefits the narrative.

The final matter at hand is that if the villain needs to trick the cast, it should still align with their ultimate motive. Some villains don’t need to hide their villainy because doing so serves no purpose, such as Hoenn’s Maxie and Archie, who are very upfront with their goals. Ghetsis, on the other hand, does attempt to trick the cast, and with flawless reason: succeeding in this goal requires the deceit—or persuasion—of the masses.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. While also defined as the art of effective communication, both written and verbal,59 this naturally lends itself to persuasion: the more effectively one can communicate, the more effectively they can persuade those they speak to, whether it be to answer a friend’s question about how your day went, or to convince said friend that Unova’s elemental monkeys are, in fact, really great and totally underrated. If you predominantly go over reasons why they’re bad, you’re not going to do a good job of convincing anyone of what you believe.

Rhetoricians are, therefore, people who convince others. Philosophers, speechwriters, public speakers, and even teachers are all rhetoricians in their own way. Everyone uses rhetoric as a means of connection, but for some people, it’s their proverbial bread and butter. Ghetsis is one such person, on the surface serving as Team Plasma’s speechwriter, public speaker, and even recruiter. According to Gorm, “Ghetsis … will liberate Pokémon with words alone,” compared to the lowly grunts who the other sages “ordered … to take Pokémon with full force.” This is cleverly displayed throughout the game: Ghetsis reappears at consistent intervals to deliver speeches to the player and other characters, but never engages in battle until the story’s finale, unlike the grunts who are always up for a fight.

His use of eye-catching visual elements such as the castle around his shoulders and the most attention-grabbing colors also play into his role as Team Plasma’s rhetorician. He commands your attention visually with his design and intellectually with his speeches. But while most people would like to think rhetoric should be used for good, for the betterment of humanity through the circulation of information and effective communication, Ghetsis twists this, too. He uses rhetoric to achieve his evil ends, by manipulating the “foolish” masses “with speeches,” just as would the monstrous serpent lurking within the perfect Garden of Eden.

Ghetsis’s misuse of rhetoric is another example of how he flips Black and White‘s themes on their head, while also tying him inseparably to the games’ man of the hour: Plato himself wasn’t the biggest fan of rhetoricians. In his Socratic dialogue Gorgias, Plato expresses, through the character of Socrates, his belief that “persuasion is the chief end of rhetoric.”60 And because persuasion—or “winning” an argument—is the goal, it offers no room for discovering areas where you may be wrong. In other words, Plato’s belief is that communication should be a way to help us learn and connect with each other—one of Black and White‘s central ideas—while rhetoric is just a way to try to win arguments, no matter how unjust the end result or how deceitful the means of achieving the result. If this sounds familiar, it’s because this is exactly how Pokémon battles are presented in the series, and especially in Black and White: N learns that Pokémon battles can be used to connect with and learn about others, while Ghetsis is trying to use Pokémon battles to subjugate the masses and leave himself as the only person with Pokémon at his disposal. If knowledge is power, then taking away access to knowledge is taking away power from everyone except those who have access.

Additionally, if the purpose of communication should be for uncovering the truth, it can’t be done if rhetoricians “need not know the truth about things” in order to find a way to “persuad[e] the ignorant that he has more knowledge than those who know[.]”61 An example Socrates uses is the physician—it’s unreasonable to think that someone who isn’t a physician, or in some related field, knows more about health than an actual physician. Even in the modern day, there’s some truth to this idea: the most effective rhetoricians are more than just rhetoricians. The best public speakers got to the position they’re in because they started off in a particular field, developed their skills, and are now informing others of what they know from practical experience. Ghetsis, on the other hand, is a rhetorician and nothing more. He’s not like Unova’s Gym Leaders, who each have their own professions in addition to manning their Gyms. What does Ghetsis do, besides using speeches to trick others into joining his “cause?” All he has is a frighteningly strong team of Pokémon, so it can be said that he at least has experience as a Pokémon Trainer. But while N’s own experience as a Pokémon Trainer leads him to believe that people gain more from Pokémon than the reverse, and therefore should be freed from humans’ ownership, Ghetsis’s experience has led him to believe that “only [he] should be able to use Pokémon.” And through communication—climactically ending in Pokémon battles—N learns the ways in which he’s wrong, while Ghetsis learns absolutely nothing, because the goal of rhetoric, according to Plato, is to persuade, not to be persuaded.

The way the rhetorician aims to persuade without knowing as much as those with practical experience is by targeting those “who know nothing,” in Ghetsis’s words. In Socrates’s: “the ignorant is more persuasive with the ignorant than he who has knowledge[.]”62 Ghetsis is able to convince the masses whenever they don’t know better, such as when he recounts the story of Unova’s founding to Burgh and Iris in Castelia City; but he isn’t able to convince them to release their Pokémon, because they have experience of working positively together with their teams. Ultimately, Ghetsis is banking on some level of ignorance from his audiences, because without that, his ethos begins to crumble. And when it fully falls away, the truth underneath comes to light: he is naught but a deceitful rhetorician working for his own gain.

Even Ghetsis’s unjustifiable actions and goals are a part of his depiction as the rhetorician. During their dialogue, the titular character Gorgias admits that rhetoric can be used unjustly, which Socrates takes as an admission that rhetoricians don’t actually know what’s just or unjust.63 If they knew what was just and unjust, they wouldn’t act unjustly—to Plato, this is the difference between the rhetorician and philosopher, with the latter always acting justly. And Ghetsis’s unjust actions hurt no one more directly or profoundly than his supposed son, N.

During Gorgias, Socrates states that “the reason why we provide ourselves with friends and children is, that when we get old and stumble, a younger generation may be at hand to set us on our legs again in our words and in our actions[.]”64 The connection between old and new, past and future, isn’t new to Black and White, but here it takes a turn: Ghetsis’s grooming of N is not for the sake of working towards a better future or for Ghetsis to have someone to right him when he becomes wrong, but so that he can have a pawn who will lead him to the singular, selfish future he desires. While fathers can symbolically stand for “reason and consciousness,”65 linking them to the philosopher and, to some extent, the rhetorician, they can also stand for dominion66 and divinity, which ties in with how many religious texts will describe a god or God as a “Father” with “supreme authority.”67

We’re once again face to face with Ghetsis’s god complex, and it won’t be going away any time soon as it leaks into his own musical motifs and, subsequently, his very identity. Of the Seven Sages, Ghetsis is the only one to not be named after a color. The origin of his name is more obvious in Japanese, where it is romanized as G-Cis, with Cis being a European notation for the note C sharp (C#). G and C# are the notes that form the foundation of his battle theme, used in the main melody, and by the timpani and vocalists.68 These notes, however, form a tritone; unlike the perfection Ghetsis sees himself as, a tritone comes “in between two perfect consonances, the perfect fourth and the perfect fifth.”69

While perfect intervals sound “harmonious” and “stable,” imperfect intervals such as the tritone “clash” and can have a “tense” feeling; and as with all tension, it feels as if it wants to resolve, to release that tension and return to stability by being followed up by a perfect interval.70 The two notes of a tritone, when played simultaneously, can be described as trying to pull themselves apart,71 not unlike the state of matter Ghetsis’s very organization is named after. This is what creates the very dissonance that has led to the interval’s moniker, “the Devil in music.”72 Contrary to popular belief, this descriptor doesn’t come from any association with the Devil but rather because the two notes are “devilishly difficult” to sing in succession.73 While a direct association with the Devil would have been perfectly appropriate for Ghetsis, the true origin behind the title still fits with his musical piece. While ascending tritones are generally described as upbeat or forceful, as can be heard in the iconic opening theme song for the animated sitcom series The Simpsons, descending tritones, like the G to C# in Ghetsis’s battle music, sound much more ominous or suitable for a funeral.74

Ghetsis’s iconic battle theme predominantly uses percussion and chanting vocals. Thanks to how they sound, drums are “associated with the symbolism of thunder and lightning,” including their association with godhood.75 It’s the same reason why Arceus’s own battle theme also prominently uses percussion. What Ghetsis’s music has that Arceus’s lacks, however, is a choir. Chants, such as the Gregorian chant, were sung in churches as a form of prayer, but Ghetsis’s own choir only chants his name, as if he is the god they are calling out to. And because they sing the notes he is named after, the choir contends with the notoriously ugly-sounding—and difficult to execute—descending tritone of G and C# instead of the perfect intervals chants tried to focus on for the sake of sounding glorious and “perfect” for their God.76 As always, Ghetsis is the contrarian: his very name is an oxymoron, with a tritone of a first name and “Harmonia,” or a pleasing combination of notes in “harmony,” for his last.

For one final glimpse at the meaning behind Ghetsis’s use of music, we once again turn to Plato, who put forth the idea that music can influence its listeners through pathos—not unlike the more positively used Relic Song, whose in-game description mentions “appealing to the hearts of those listening.” But Plato still ultimately believed that music, like all arts, was naught but an imitation of reality, with reality itself already being an—imperfect—imitation of his perfect Forms.77 And what better way to describe Ghetsis than that? Ghetsis is an inferior imitation of the godhood he seeks. No matter how long he plans, no matter how many resources he gathers, he simply cannot overcome the heroes he has inadvertently shaped through his schemes. As powerful and frightening as Ghetsis is, he is no god. Instead, Ghetsis is evil; and “evil,” being “just a privation—or, a lack of—good” has no place in Plato’s perfect world of Forms.78 And Ghetsis, being entirely evil, is absolutely not perfect.

What even is “perfection?” A miserable little pile of definitions: for something to be “perfect,” it can’t have any flaws.79 But what are “flaws?” In simple terms, it’s a defect or a fault, “one that detracts from the whole or hinders effectiveness.”80 But what determines if something is effective or not? For some things, flaws and imperfections are easy to ascertain: if a car doesn’t start, something is wrong. If you replace the variable x with the number 2 in the equation “1 + x = 2,” it’s simply not going to work.

But for endeavors with more emphasis on creativity such as video games and storytelling, “effectiveness” isn’t black or white but instead a lot more gray. It can be argued that Pokémon Musicals are, put simply, quite bad, but since they’re entirely optional, their ineffectiveness doesn’t detract from Black and White‘s overall effectiveness. It can separately be argued that Ghetsis is an ineffective “twist villain,” but as already discussed, that “flaw” actually works to his advantage when considering the structure of Black and White‘s story.

The reason why “there is no such thing as a perfect game” or “perfect story” is because no matter how heavily you arm your arguments with evidence, there will always be somebody out there who simply disagrees. That doesn’t mean their opinion is entirely valid, as opinions should be built upon concrete evidence, but their feelings certainly are. Nothing is perfect because everyone’s definition of “perfection”—everyone’s feelings over what makes something a “flaw” or not—is different, and thus no single thing can be “perfect” to everyone. But some things can be “perfect” to individuals. The same thing can even be “perfect” to the same group of people, but each individual has an entirely different reasoning. Everything has “imperfections,” from the media we consume to ourselves as we learn and grow. It’s what we do with—and how we contextualize and utilize—those imperfections that makes something perfect.

Imperfection is a natural part of being human. But Ghetsis is portrayed more as a monster than a human. This seemingly one-dimensional character is highly intentional, as he can thusly serve as a foil to N’s complexity while also filling in an important gap in Black and White‘s themes: while it’s true that seeing eye-to-eye with people whose beliefs are different than our own is how we grow, this only works to a certain extent. There are certain beliefs that simply should not be accommodated for and certain people who are not willing to engage in meaningful attempts to improve themselves. No amount of backstory or reasoning could serve as justification for beliefs and actions as harmful as Ghetsis’s, so he rightfully doesn’t receive any. Everything about Ghetsis’s execution as a villain works to ensure that both the black and the white are accounted for in Black and White.

It stands to reason that perfection can’t exist without imperfection, but in reality imperfection can exist without perfection, unless you change your perception of perfection. Ghetsis’s own definition of perfection is one that’s easily disagreed with, with only his sinister self being perfect in an imperfect world that won’t let him get away with his schemes. But for many, the Pokémon world is already perfect—Ghetsis notwithstanding.