Part I: The Components of Unova

For the anniversary of the release of Pokémon Black and White, we release our tribute to the games. Part I focuses on gameplay and other mechanics, as well as their themes.

Part I: The Components of Unova

Hexagons | Adventure | Dreams | Seasons

Discovery | Myths | Sprites | Music | Accessibility

The Trains of Unova: The Perfect Unity of Accessibility

The argument that Black and White “have no post-game” is usually followed with “therefore, they’re bad games.” This idea is wrong on two fundamental levels: firstly, Black and White do have a post-game. They actually have a huge post-game. Secondly, having—or not having—a post-game isn’t indicative of a game’s quality; to reach the post-game at all, one must get through the main game, that adventure being the primary reason for playing Pokémon. The idea that Black and White lack a post-game, or content accessible only after the credits roll, comes from their lack of Battle Frontier, a competitive-level collection of almost exclusively single-player battle facilities, including the Battle Tower. But why should the Battle Frontier be the sole feature required for a post-game, and the sole determining factor of whether a game is good or not?

The first set of games in any given generation always lacks a Battle Frontier or equivalent, while also lacking much post-game content in general. When considering the short length of Gold and Silver’s Johto, it’s easy to consider Kanto as simply the second half of the main game, but that leaves the titles with very little post-game. Ruby and Sapphire similarly lack much post-game content, with Sky Pillar and the Battle Tower as the main attractions. Diamond and Pearl followed Ruby and Sapphire‘s lead, even though Emerald introduced the Battle Frontier. Not only was it natural—practically inevitable—for Black and White to not feature any sort of Battle Frontier when considering that its first-set predecessors also never included one, but the changing needs of players combined with Black and White’s emphasis on connection naturally lends itself to seeking accessibility. Instead of opting for a significantly inaccessible Battle Frontier, an approachable yet challenging three towns, five routes, two bridges, and four explorable landmarks open up after the credits roll, complete with multiple superboss battles and, of course, a Battle Tower. In the end, Black and White actually have one of the biggest post-games in the series, and it’s one that anyone and everyone can enjoy regardless of how much or how little they want to get into competitive teambuilding.

Competitive teambuilding and play overall has its own “accessibility curve:” more and more players become interested in competitive play as time goes on because each new generation improves the process of getting started. Put another way, the older the Pokémon games become, the harder it is to get into competitive play. The reason why the Battle Frontier isn’t very accessible is because such facilities feature opponents with teams that are more fitting in competitive play than in the main storyline, meaning players will want to tackle them with similar teams of their own. Unfortunately, IV breeding and EV training—the methods with which to craft these competitive-level teams—have always been an exercise in pain tolerance, and have only been made more bearable starting with the sixth generation of games.

Additionally, actual competitive play is far more practical than a Battle Tower or Frontier—you’re playing against real people rather than AI opponents, allowing players to practice outmaneuvering or “mind games.” It’s also infinite in value—once you get the gold “trophies” from each Frontier facility, you have no direct reason to play any more, whereas you must continue playing online to maintain your ranking or try to increase it. As a result, more recent games in the series have naturally shifted away from the Frontier and instead prioritize improving online play.

Still, the Battle Tower remains in each game as a way to further ease players into the ways of competitive. The opponents are challenging enough to encourage players to start competitive teambuilding, but are also simple enough to “clear” in a reasonable amount of time compared to the more complex Frontier facilities. Considering that Black and White already place emphasis on connectivity through their plethora of new features, such as the previously discussed Entralink, it’s only natural that its approach to competitive play tones down the single-player Frontier and instead offers a simple Tower as a springboard for interested players. All the while, the bulk of the post-game actually lies in the highly accessible latter half of the Unova region that will be discussed in more depth in Part II. Put simply, players who aren’t interested in competitive play wouldn’t bother with the Tower and wouldn’t be able to engage meaningfully in the Frontier, but all players can play Black and White’s post-game because it’s structured like the rest of the game is: routes, towns, Trainers, and wild Pokémon that you can approach with the same team you’ve already been using if you so choose.

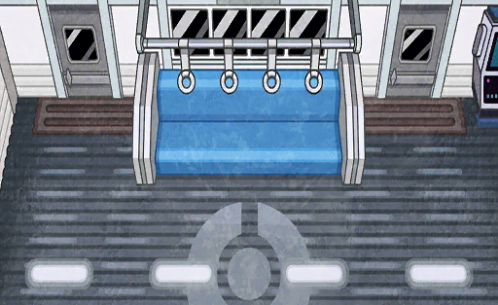

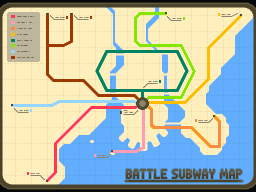

Players who do choose to engage with the Battle Tower of Black and White will find that it, like the rest of the games’ features, is filled with meaningful symbolism. In Black and White, the Battle Tower takes the form of the Battle Subway, which can be accessed in the Gear Station in Nimbasa City. Trains carry with them as many symbolic meanings as passengers, as indicated by their common recurrence in various media. From Chris Van Allsburg’s classic The Polar Express to the partially submerged train in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away and even the midnight train going anywhere in Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’,” train iconography is stunningly diverse throughout its history.

By taking people across long distances, their purpose of traveling turns into one of connection, connecting the people who travel as well as connecting the places being visited. It’s here where Black and White’s emphasis on exploration becomes most clear: it takes an element that is used to improve the game mechanically and applies it to a narrative theme. Focusing on exploration isn’t just a convenient way to welcome fantastic level design—it’s also directly tied to the idea of how “adventures” can help us grow. As Alder will later insist, traveling is wonderful because seeing new places, experiencing new cultures, and meeting new people who have different beliefs and ideas than you challenges you and expands your horizons.

As a symbol of travel, the train naturally fits into this theme of exploration and adventure, and the Battle Subway continues this seamlessly. The battling lines take players to challenging fights that can improve their skills; the brown line, however, has no battles whatsoever. Like the rest of the Battle Subway system, it’s accessible through the Gear Station, but unlike the battle lines, the brown line can be boarded before beating the game. It takes you to Anville Town, a little hamlet with a turntable that shows off different kinds of train cars. On weekends, more NPCs make their way there to trade items, making small but meaningful connections with each other and the player.

As a symbol of travel, the train naturally fits into this theme of exploration and adventure, and the Battle Subway continues this seamlessly. The battling lines take players to challenging fights that can improve their skills; the brown line, however, has no battles whatsoever. Like the rest of the Battle Subway system, it’s accessible through the Gear Station, but unlike the battle lines, the brown line can be boarded before beating the game. It takes you to Anville Town, a little hamlet with a turntable that shows off different kinds of train cars. On weekends, more NPCs make their way there to trade items, making small but meaningful connections with each other and the player.

If travel, exploration, and adventure offer the opportunity for individuals to grow, it makes sense that different modes of transportation are brought into focus in the games. In addition to the Battle Subway, trains constantly traverse beneath Tubeline Bridge. Abandoned train tracks can be found in Nacrene City, tying into the changes brought about by time—we may still need trains, but some will fall into disuse just as we maintain some of our traditions and cast off others. Another post-game treat besides the Battle Subway comes in the form of riding the Royal Unova, a cruise ship with Trainers to battle inside the cabins and lovely sights to see on the deck. The other major modes of transport, cars and planes, aren’t accessible to the player, but still feature prominently throughout Unova: cars zoom past beneath Skyarrow Bridge and on the bridges above Route 4, while Mistralton City’s planes park on the runway, waiting for their time to carry cargo to far-off regions.

But the Battle Subway reigns supreme in this area, offering the opportunity for both tough battles and an exclusive area that can be accessed through no other method. In Anville Town, collaboration between people is brought to the forefront with the town’s item trading gimmick. Like the rest of Black and White, players are rewarded for treading off the main path with something that serves both a worldbuilding and gameplay purpose, even if the items aren’t strictly necessary to complete the game and even if the worldbuilding isn’t crucial to the main story.

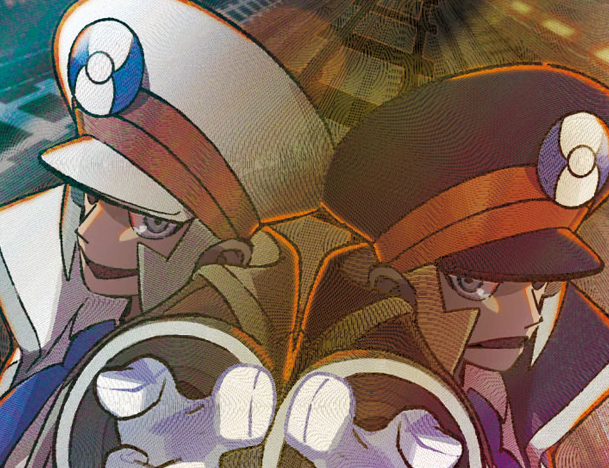

Similarly, Ingo and Emmet stand out among Black and White’s cast as the only named characters without direct plot relevance. The Battle Subway itself isn’t plot relevant, so this should come as no surprise; as the bridge between “casual” single-player gameplay and “competitive” online play, the Battle Subway doesn’t need to force itself into the narrative and risk overcomplicating matters. But the men who oversee the facility still follow through on the effective themeing found throughout Black and White. Ingo and Emmet are polar opposites: up and down, in and out, black and white. Even in terms of mannerisms, they’re as stark as night and day. Ingo’s perpetual frown doesn’t stop him from being highly emotive, and he speaks in a fairly normal manner with longer sentences naturally interspersed with shorter ones. Emmet’s permanent smile, on the other hand, belies his practically robotic personality complete with unnaturally short and oftentimes repetitive sentences.

Similarly, Ingo and Emmet stand out among Black and White’s cast as the only named characters without direct plot relevance. The Battle Subway itself isn’t plot relevant, so this should come as no surprise; as the bridge between “casual” single-player gameplay and “competitive” online play, the Battle Subway doesn’t need to force itself into the narrative and risk overcomplicating matters. But the men who oversee the facility still follow through on the effective themeing found throughout Black and White. Ingo and Emmet are polar opposites: up and down, in and out, black and white. Even in terms of mannerisms, they’re as stark as night and day. Ingo’s perpetual frown doesn’t stop him from being highly emotive, and he speaks in a fairly normal manner with longer sentences naturally interspersed with shorter ones. Emmet’s permanent smile, on the other hand, belies his practically robotic personality complete with unnaturally short and oftentimes repetitive sentences.

These two brothers also differ in their battle style of choice, with Ingo preferring Single Battles and Emmet preferring Double Battles. But as Black and White emphasize, strength comes in all shapes and forms; in this case, just because one is better at Singles or Doubles doesn’t mean he’s the inherently better Trainer. Just as Alder again will insist, both have found their own version of “strength,” and as such excel at different things; and just like the brothers of legend who will play a central role in Black and White’s mythos, both stand as equals to each other despite their differences. And when these two unlike forces combine—in the two-on-two Multi Train challenge—the result is something better than before: in this case, one of the most challenging boss battles in the entire game. As Ingo puts it after the player defeats him and Emmet on the Super Multi Train, “When you and someone else combine, your engine powers something special!”

And it is something special when a game can balance a more accessible post-game of additional fun areas to explore with a stepping stone into competitive play. Black and White know where their focus lies both in terms of gameplay and themes, and just as it’s important to know when certain characters should step back, it’s also crucial to know when certain unnecessary gameplay features should be toned down. Instead, the spotlight is shone on a different kind of post-game, one that focuses on further fleshing out Unova—one that has its own strengths and works perfectly with Black and White’s goals.