Closing

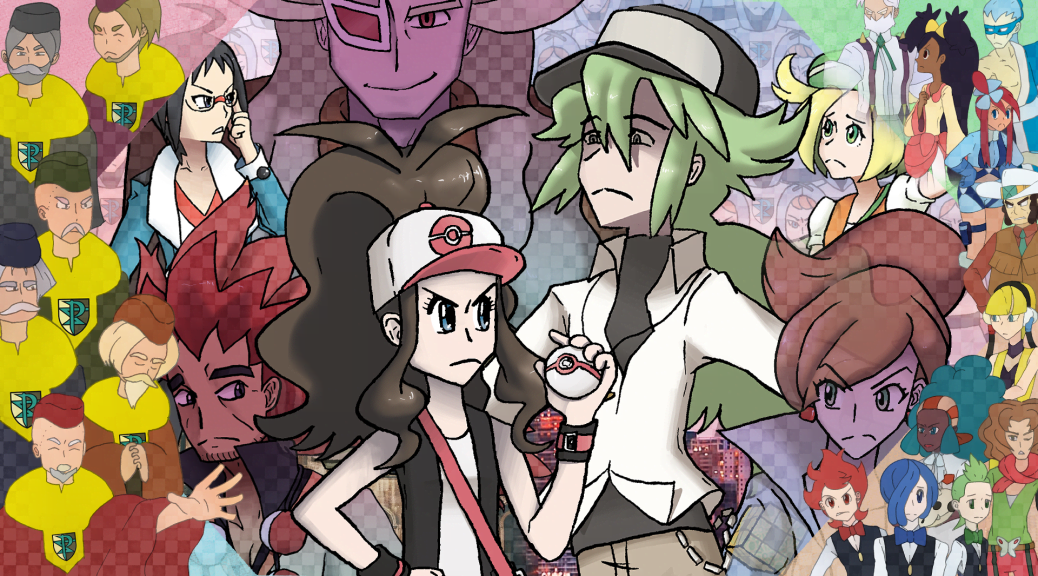

Our tribute to Pokémon Black and White ends with a conclusion and some final words.

Conclusion

If anything represents “conflict,” it’s the Pokémon series of games. The primary narrative conflict against a greater evil is at complete odds with the underlying goal of becoming the Champion, leading to two unrelated plotlines trying to one-up each other and barely converging in the process. Side characters also can’t be too important; their conflicts can’t constitute the game’s primary conflict because you, the player, must be the one who resolves it. Your rivals can never be too much of a threat because you, the player, must always be the one who wins to progress through the game. Your villainous adversaries can similarly never stand a chance against you, and they can also never be too justifiable, otherwise it would feel wrong having to so thoroughly trounce them.

Mechanically, the Pokémon games are still the blatant manifestation of conflict: the formulas that keep the series financially successful are entirely unsustainable. As just one example, adding close to or even more than 100 new monsters each and every game makes it increasingly difficult to maintain backwards compatibility. The unfortunate reality is that Sword and Shield‘s “Dexit” was an inevitability—it was only a matter of time before the games couldn’t have every Pokémon programmed into them, given their short development periods. The short development periods themselves are another rigid formula, because they allow those 100-or-so new Pokémon to be created and subsequently merchandised at consistent intervals.1

Even the overall franchise’s merchandising emphasis on “catching them all” is at odds with the main series from which everything stems. With the singular exception of Legends: Arceus, the mainline games have never been about catching more than they’ve been about battling. You technically don’t even need to catch anything before you can start battling thanks to your starter Pokémon always being a gift. You also never really need to “catch ’em all,” since filling the Pokédex has always been nothing more than a fun little bonus that didn’t even offer any practical incentive to complete until after Black and White.

Combine narrative formulas and mechanical formulas, and you’re suddenly faced with further disaster. The very battles that form the basis of this series run on logic that can at times almost sound like victim blaming: trust me, your Pokémon just love battling to the brink of death! There’s nothing unethical here! But those very battles are a key factor in the formula that keeps the series going strong close to 30 years later.

It’s no small feat to create a meaningful, nuanced plot out of the constraints and necessities of the mainline Pokémon series. The original games were not developed with story in mind. Simply developing the mechanics of the games was a massive undertaking for the then-small Game Freak, with only 17 different names appearing in Red and Green‘s staff roll. Many of the series’s long-running iconic elements were last-minute additions, such as the Grass type itself, one of the foundational types of every games’ iconic starter trio. It’s been posited, based on discovered beta information, that the type wasn’t added until very, very late into the development of Red and Green. In fact, it was added after the addition of the starters themselves, which were originally meant to be not a trio but a duo.2

Undergoing such extensive levels of alteration also means that what little lore the games were meant to have took their own twists and turns. By the time the project was finalized, the lore that made it through the development wringer unscathed couldn’t fit into the game cartridges of the time, and were instead provided in supplemental media. These official sources depicted scenarios that likely wouldn’t have made it into the final product even if there was space: for example, one Japan-exclusive book describes how Poké Balls were invented. A Pokémon professor in 1925 made a Primeape overdose on drugs, causing it to curl up into a fetal position so small that it could fit into the professor’s glasses case. Yes, really.3

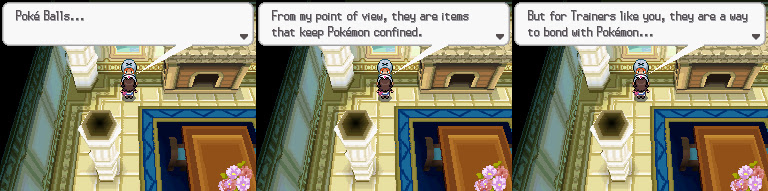

On the surface, it may seem like such lore has been retroactively discarded from the series canon due to no longer being referenced. The family-friendly Pokémon universe can depict abusive and neglectful parents, but it certainly wouldn’t do to make any reference to drugs! But just like how the series hasn’t forgotten its roots in terms of its nearly unchanging gameplay, even this kind of older lore hasn’t been fully retconned out of existence. Decades later, the classic Poké Balls in Legends: Arceus would be described as possessing a similar—albeit less drug-induced—Pokémon-shrinking property as their “original” counterparts. With that level of consistency in mind, is it any wonder that Team Plasma thinks Poké Balls are bad?

The formulas that resulted in the Pokémon world were mere happenstance, a miraculous Big Bang that birthed the most powerful intellectual property our world has ever seen. But basing an entire series on such a formula comes with its share of limits and challenges. How does one deviate narratively when forced to conform to standards built for the most simplistic storytelling possible?

This is where Black and White performs its own miracle: it tells a powerful story under the confines of a mainline Pokémon game. It does this by taking the very foundations of the series and assigning them narrative relevance. It’s a simple solution, but one that works precisely because the conflict with the primary antagonist revolves around the mechanics of the game: catching and battling Pokémon. The series’s tropes are used as creative limitations, but not the kind that limits as a fence does: instead, they serve as a building foundation that can be built upon, with characters and themes that naturally stack upon each other and rise up and beyond the clouds, like a New York City skyscraper.

Drawing on one of its very own themes, Black and White moves the series forward because it knows where it has come from, both narratively and mechanically. Our pasts will always influence our future, whether that be for us to know what we should continue doing or to decide what we should change. But in order to determine which is which, we have to look past our intents and truly understand the complex outcomes of our prior actions and beliefs.

Things simply aren’t ready to go without revision, even when approached with the best of intentions. Writings must be revised, illustrations reworked—after already being developed from multiple thumbnails—and video games playtested and tweaked until their difficulty is balanced just right and any bugs are ironed out. And individual projects don’t exist in a vacuum: when writing a new story, painting a new picture, or developing a new game, you’re drawing on your knowledge that comes from your past experiences.

The reason why things get better over time is because with time comes experience—but there’s a catch. It’s been proven that people only “learn from experience” when that experience comes with increased feedback from others. Without external feedback, people will fall back on their biases without even realizing it, leading to stagnation rather than growth.4 When just starting out in something, we take inspiration from others, like our favorite artists or writers. Once we get our footing, we need others to give us feedback in order to know what we’re doing well and what isn’t working. We must be challenged in order to grow, but in order to be challenged, we still must produce something, must find a way to put our ideas, our very dreams, into the world.

What Game Freak put into the world was Pokémon Red and Green. As its first foray into the world of RPGs, the games were plagued with bugs and balance issues. But by the time Black and White came around, the developer was armed with all manner of experience, including level design, sprite work, an eye for narrative, and a clear goal in mind for its end result. And Game Freak got to this point at all thanks to its experience and feedback from the prior four generations of Pokémon.

This isn’t to say that all feedback is inherently helpful, however, especially when your actions—or projects—reach an unfathomably large audience as Pokémon does. Like all conflict, there’s more than one perspective on what the best solution is—what’s the “best way” to approach a Pokémon game—and there’s simply no way to accommodate for them all. Pokémon‘s rigid confines of both its mechanical requirements and its strict developmental deadlines are, for better and worse, non-negotiable; from here, Game Freak could take feedback from players and from the individuals within the team to craft the most quintessential Pokémon experience possible.

It’s that self-awareness that is imbued into Black and White‘s very essence. The game isn’t just a retooling of a series that can do no wrong—it’s a critique, holding up a mirror to the foundations of the series and asking, “Do we need this? If so, why?” Doing so allows the game to work with rather than against its own confines. As the saying goes, “limitation cultivates creativity.” And for a game so evaluative of the series’s foundational limitations, it only makes sense to metaphorically return to square one, from where those limitations stem.

Black and White is generally referred to as a “soft reset” of the series, with only new Pokémon appearing during the main storyline, and many of them paralleling those introduced in Red and Green. But the parallels run far deeper than that. Black and White takes what was born from a group of good friends and bad coding and turns them into intentional narrative choices. Even some of Black and White‘s exclusive mechanics are throwbacks to the hopes of Red and Green that couldn’t come to fruition without proper experience. One such example is how series creator Satoshi Tajiri originally wanted regional differences to appear from version to version. While this wasn’t possible to execute at the time,5 regional differences were finally implemented—and with thematic relevance—in Black and White through Black Version‘s futuristic locales and White Version‘s rustic settings. Adding even more intentionality to this choice is the fact that no other Pokémon games do this: there may be different NPCs between version counterparts, but the region they appear in stays the same between games. The version-exclusive Gym Leaders of Sword and Shield may be found in Stow-on-Side and Circhester, but the settlements themselves have no version differences of their own. And the only differences between the “version exclusive” locations in Alola, the Altars and Lakes of the Sunne and Moone, are the placements of the sun and moon engravings.

One of the biggest references to the original games that drives home the intentional parallels is actually lost on international audiences: the color opposite of red isn’t blue, but green. Sitting directly opposite to each other on the color wheel, mixing red and green together results in gray. Opposite colors are referred to as complimentary: they stand out the most when beside each other and add visual interest to whatever it is they adorn. Their drastic differences bring out the best in each other, just like how our own differences make the world a richer and more vibrant place.

While Pokémon games are doomed to repeat themselves on account of their identical formulas, Black and White instigated a major shift for the series. There had always been hidden pockets of depth to Pokémon narratives before, such as Silver’s character arc in Gold, Silver, and Crystal and the politics behind Team Magma and Team Aqua’s motives in Ruby, Sapphire, and Emerald. But Black and White truly kicked off the series’s focus on character-driven storytelling—and, on a less obvious level, a spell of self-reflection. Although Alola deviates the most from other regions due to its lack of Gyms—trials being Gyms in disguise aside—Prof. Kukui still implements an Elite Four to replicate what he experienced during his travels. No matter how different Pokémon games strive to be, all roads will ultimately lead to Rome—or in this case, to Kanto.

In Sword and Shield, becoming the Champion is so heavily engrained into Galar’s culture that Trainers generally can’t fathom other options. Gym Leaders don’t take on the role to help up-and-coming Trainers hone their skills; they become Gym Leaders to guarantee their spot in the Champion Cup in hopes of challenging and becoming the next Champion. Even worse, when Sonia is first introduced, Leon can’t even think of anything nice to say except that her cooking is edible. While Sonia dubs herself as Leon’s rival during their Gym Challenge, Leon later states, “Raihan is the only Trainer out there I consider a real rival.” In this region where every Trainer’s focus is on becoming the Champion, being great at battling is what matters most. Is it any wonder, then, that Hop is so anxious to become a researcher himself, after seeing how Leon regards Sonia? What would Leon, and his own rival, the player, think of him then?

In Galar, the Gym Challenge stifles everything else—becoming the Champion is what all Trainers absolutely must strive for, no questions asked, as Cheren believed at the start of his own journey. The confines created by the Gym Challenge serve as the main point of conflict for the main characters, and even for the secondary characters, as the energy used to keep the stadiums running and to broadcast battles is leading Galar to its doom, according to Chairman Rose. Sword and Shield‘s supplementary media tries to recontextualize the characters’ conflicting feelings as them not having time like they used to once they gained more responsibilities, but it’s clear the seeds of self-reflection were planted in the games—they just weren’t given what they needed in order to fully grow. Similarly, Sun and Moon‘s self-reflective edge is dulled when considering how neither Team Skull nor the Aether Foundation play into the theme as strongly as Kukui’s ambitions do.

Once the door to meaningful, character-driven writing is opened, there’s no stopping interpretations from pouring in. And interpretation is an absolutely wonderful thing: everyone, with all their differences, can find something meaningful, no matter how large or small, in the works they consume, bringing them together even if their ideas differ. There’s also no such thing as a “wrong” interpretation, just interpretations with more and interpretations with less evidence from the original work backing them up. But there’s something that makes Black and White special: no matter what theme you choose to focus on, the game’s characters and even its mechanics find a way to successfully slot themselves in, like perfectly tessellating hexagons that can be rearranged as needed. Black and White is just as much about how our pasts influence our futures as it’s about how we must escape our metaphorical caves to discover our own light. That’s because Black and White are, first and foremost, Pokémon games about Pokémon, the series. The themes are applicable to the series as a whole, not only in regards to their finished products, but the way they’re made.

Interpretation also helps us discover ourselves. Which of Black and White‘s themes resonates the most with you, and why? Those “why’s” are important—it’s the difference between N wanting to become Champion for the sake of liberating Pokémon, Cheren wanting to become Champion “just because,” and Bianca not even knowing what she wants to become. As we discover our “why’s”—why we like the things that we like; why we do the things that we do; why we stand for the values that we stand for—we become more intentional about our choices, just as Game Freak was intentional with the “why’s” behind Black and White.

Just like the seasons cycle, we must cycle back to our interactions with others in order to discover our “why’s.” We must be open to having our opinions challenged in order to truly cultivate them. But we also shouldn’t just change our opinions without serious consideration. It’s not an easy act to balance, but if Black and White can balance all of its deeper themes, then anything is possible.

Black and White were built upon four prior generations of hard work, gained experience, and the developers’ dreams for a video game that would capture the magical feeling of catching bugs when school was out. As the series grew in popularity, it took on the dreams of its dedicated—and endlessly expanding—audience, just as our dreams are influenced by the people we meet and the circumstances around us. Just as it took considerable time for Black and White to come to fruition, it’s a time-consuming process to make our dreams come true; seasons may pass, and our dreams themselves may change—everything gets better with revision, after all.

Pokémon has since come to represent something much greater than just a child’s summertime adventure. It’s brought people together and inspired them to fulfill their dreams. We may not have Pokémon by our sides in our world, but we have the next best thing: the Pokémon games themselves, with their stories, characters, and, yes, even their Pokémon. And if there’s any Pokémon game that represents how the series can be so influential, it’s Black and White—just like how if there’s anyone out there who can make their dreams into reality, it’s you.