Conflicting Egos: The False Beauty of Kalos

You are about to enter the beautiful Kalos region: a region built on the tragedy of a war long past. Join us on a tour of X & Y’s themes of life, loss, and obsession, and the three great men who embody them.

Conflicting Egos: The False Beauty of Kalos

You are about to enter the beautiful Kalos region: a region built on the tragedy of a war long past. Join us on a tour of X & Y’s themes of life, loss, and obsession, and the three great men who embody them.

Written by Rivvon

“I apologize that the weapon was unearthed even after you chose correctly in the lab. But conflicting egos drive this world—things don’t always go the way you want!”

Lysandre

The Kalos region: beautiful flowers sprout from well-kept earth. Sparkling rivers and streams drape across the land. There are plenty of cafés to visit, where you can enjoy a pleasant drink and meet kind Kalosians. You can visit one of the many boutiques and dress yourself up however you please. The Kalos region: beautiful.

And yet there exist people who would wish to dirty it… Turn it into filth with their selfish, stupid ways. Take the limited resources the region—no, the world—has all for themselves and lash out towards anyone who tries to make them share.

…Or, that’s what Lysandre wants you to believe. But is it the truth? Pokémon X & Y feature a plot centered around an evil team whose goal is to wipe out life on earth in an attempt to return the world to a clean slate, where only the chosen elite would live in harmony. With the Life and Destruction Pokémon gracing their covers, X & Y’s narrative features themes in line with their titles, such as loss and the duality of life and death.

With such mature themes at its core—maturity in plot being something older series fans generally wish for—how could it be that the narrative of these games turned out to be almost universally considered a disappointment? Are these fundamental themes shaky, was the execution flawed, or was it perhaps a little bit of both? If you remove those Team Flare-issued glasses, I can take you on a tour of the true Kalos, with all its false beauty.

“In our brief lives,

we’ve managed to meet.

Treasure this gift,

this precious time that we have.”

KISEKI

Bonds are a major theme in the attempted plot of X & Y. Some of the earliest characters you will meet are based around this theme. Your friends, Shauna, Tierno, and Trevor, travel across the region at the same time as you, and occasionally cross paths with you, all in an attempt to make the player feel as though they are traveling with a group of close friends. While there exists “positive bonds” and “negative bonds,” the friends in question were certainly intended to represent the positive ones. Although they may be a bit awkward at first, they are all very supportive of the player. But despite that, it is difficult to develop bonds with characters you do not like, and it is difficult to enjoy characters who are presented as very uninteresting and undergo no development whatsoever.

Each of your friends has their own unique goals. While they do (rarely) challenge you to standard Pokémon battles, their overall goals aren’t related to being your typical Trainer: Tierno wants to create the world’s best Pokémon dance team, Trevor wants to fill his Pokédex, and Shauna herself admits she’s just kind of along for the ride, hoping to make wonderful memories with her new friends and her new Pokémon. This is all rather endearing, in actuality. These characters feel different from previous ones whose primary goal was to become “the best Pokémon Trainer,” and in a way they feel more real; if Pokémon were real, there would certainly be more professions besides Trainer and Professor. These are usually reflected in the regions’ standard Trainer NPCs (for instance, Unova has bakers and break dancers, while Johto has firebreathers and jugglers), but they are not as frequently put forward as a primary characteristic of major characters (save for Gym Leaders, who frequently have a theme associated with them). They may even refer to the player by a nickname chosen near the start of the game, derived from the Japanese method of referring to close friends with more informal honorifics and sometimes even shortening their name, and localized similarly—a very cute touch that hadn’t been utilized in Pokémon games before.

But these characters’ unique charm ends here. Tierno never makes any progress on his goal—he simply catches Pokémon who know moves with “Dance” in the name. And while he seems to have his act together more so than the other two, in that he never really questions what he does and is extremely set in his aspirations, he never acts as a pillar of support or wisdom for anyone, in turn making his lack of development feel like a void where something should be.

Trevor also seems fairly set in his dream of completing the Pokédex; occasionally he asks the player to compare Pokédexes to see who has the most pages filled. Although he seems content enough, describing these little “challenges” as his “own kind of Pokémon battle,” near the end of the game—when the player has to challenge each friend atop a bridge—Trevor beats himself up after losing in a standard Trainer battle. What could have been a unique internal conflict over the course of the game of Trevor debating whether just completing his Pokédex is a “worthy” enough task ends up being delegated to approximately three lines of dialog at the very end of the story. This does not offer any room for character development and instead leaves the player wondering why Trevor is getting so worked up now when he’s been happily filling his Pokédex and not battling for the entire time leading up to this point.

Shauna is the final friend character. She is very clearly the one the writers want the player to like the most. She spends more time with the player than Trevor or Tierno, including in the well-known fireworks scene in the Parfum Palace. After reuniting the palace owner with his lost Furfrou, the player and Shauna are invited to watch fireworks together. While it is clearly intended to be a scene for the player to bond with her, with her admitting it was a great experience since she could share it with the player, if the player doesn’t already feel some sort of connection with her, the scene does not fulfill its purpose. In other words, if the player already finds Shauna a nuisance—which is incredibly likely due to the very invasive nature of the friend characters—this scene does nothing to change that.

She spouts the same tagline as always: she’s happy to make a memory with her friend. But why should the player care? Her desire to make memories never amounts to anything. Yes, she does make memories because she does do things over the course of the story, but why are these memories so important to her? Why are her memories with the player more important than, say, memories of her family, or her past friends? The only other aspect of her character, enjoying puzzles, only serves as an excuse to shoehorn her into the plot’s climax with Lysandre (where you will need her to use a puzzle she got from Clemont to open the door to the Legendary Pokémon’s room) rather than to give her any sort of depth. And by the game forcing her into more and more of these situations where she really isn’t of any help, the player grows to like her less and less. Not to mention you begin to question where your other two friends are, since it’s always Shauna who is given the larger role and not a mix of the three friends, which takes away from the overall immersion.

There is definitely a lot to be said about the absolute wonders of friendship. In reality, a moment like the fireworks scene would be very special if shared with a dear friend. But to share it with someone you don’t like, on the other hand, leaves you feeling like you wasted a good chunk of your time. These friend characters come out of nowhere and in a sense force their friendship upon you, and then act as hand-holding tutorial characters for a good portion of the start of the game. While it is very kind of them to offer you your starter Pokémon (a gesture I very much appreciate) they ultimately come off as more annoying than friendly. This causes the subsequent times they appear to feel exasperating or, in the most obvious case of visiting the “haunted house,” complete wastes of time, where nothing at all is gained from the experience. Sure, you make a memory, but what good is that memory if it doesn’t add to your character? Memories are life experiences you look back on, and the best life experiences are ones you learn and grow from. But there is no growth present in any of your friends in X & Y, leaving the memories you make with them forgettable at best.

“Battling with you is fun, but losing all the time doesn’t really make me look all that good.”

Calem

A common trope in Pokémon games is to have one or two characters act as the player’s “rival”—a character who is more focused on challenging the player to Pokémon battles periodically as the game progresses. In X & Y there is one “rival” character: if you play as the female character, your rival is Calem, and if you select the male character, your rival is Serena. For simplicity’s sake, I shall refer to Calem specifically, but these upcoming points can be applied to Serena as well.

Calem is introduced as your neighbor with parents who are great Trainers in their own right. It is heavily implied that his father is an NPC in Snowbelle City, and his mother stays behind in his home in Vaniville Town, but at the end of the day they are, in every right, nameless, generic NPCs; it’s even very easy to go through the games without speaking to them at all. We don’t even know just what their accomplishments are to warrant these titles of “Great Pokémon Trainers,” but there’s no reason to not believe what Calem says—after all, because his parents are so great, Calem himself feels he needs to follow in their footsteps and become a great Trainer, too. While there are certainly more interesting ways this “backstory” could have been handled, it does offer a different goal than the ones held by your friends, while also giving Calem a sense of familiarity: players who are acquainted with older Pokémon titles will instantly recognize his character trope and understand that he will be the character to measure the player’s progress throughout the game. So while the foundation of his character is neither new nor groundbreaking, that by itself is not inherently problematic.

What causes trouble is the set-up he is given which ends up amounting to nothing at all. In past games, rival characters reacted differently to losing to the player, some dismissing it as “dumb luck” on the player’s part, and others using the loss to encourage themselves to improve. Calem is a little different, but not in a good way. After losing so many times, his defeat dialog becomes more and more clearly frustrated: I genuinely felt that he was going to start giving the player the cold shoulder because he was so clearly upset by losing. But at the drop of a hat he’s back to helping the player, giving them Items and even battling alongside them. His obvious inferiority complex is included but not utilized at all, giving players the idea that he will show development accordingly, when in reality what happens is it’s brought up then discarded without any mention or thought whatsoever.

I find this to be a particularly strong offense primarily because of Pokémon‘s primary audience: young children. Elementary-aged children generally feel conflict is “the destroyer of friendships.” One argument, one disagreement, and you can’t be friends any more. But as you grow older you discover that’s not the case; even the best of friends, family, spouses, anyone and everyone will have disagreements sometimes. Sometimes Person A will do something that upsets Person B. But that does not signal the end of a relationship. Proper communication can lead to conflict resolution, which I feel is severely under-utilized in Calem’s case. It’s clear he’s upset by the player defeating him time and time again, but that character point is discarded in favor of showcasing friendship through a distorted lens—even though you’re rivals, you’re still friends, and friendship never goes through any rocky or tumultuous periods. That’s the message delivered by dropping Calem’s character development, and I feel it’s particularly disappointing when not only has another character been deprived of any proper development, but the development he could have had would have served as a great message to the games’ primary audience.

Similarly, because Pokémon is competitive in nature (not in the way of competitive play, but rather in that there’s a winner and loser at the end of each battle, making it into a competition), Calem’s character could have been utilized to show that losing is alright. Even the best Trainers lose sometimes; it’s natural and valid to feel frustration after losing, especially when losing to the same person over and over—and in the case of Calem, a person who has less experience than himself (kind of; I assume this is what they were going for when they added the background of Calem’s parents being great Trainers). What’s important is to keep trying, to measure your improvement against yourself rather than against others, and to not let these setbacks and conflicts get in the way of your relationships with others. While Calem does exhibit this last point, he does so in a way that does not contribute to any sort of believable growth.

Because your rival falls into the trap of trying to portray bonds as something that can never hit a rocky patch once formed, he loses all impact and chance for character development. This is made even more disappointing when you consider that Calem’s character development could very easily have acted as a catalyst for the development of the player’s other friends, too; by Calem perhaps needing some time to himself, or showing he is upset by constantly losing, the friend characters have one more event to react to, to learn from, and to grow from. And Calem going through the nuances of having a rough patch in his relationship with the player, and then overcoming it, could have potentially made his assistance in the Team Flare Secret HQ more meaningful, because he would have felt like a real friend. But in the end, he and the rest of the group is lost to the abyss of forgettable characters that the game wants you to care for, but the player just can’t bring themselves to do, because there is nothing about them that makes them feel like true friends.

“I’m just so glad at this moment that I was good enough to be the Champion… After all, it gave me the chance to meet and battle with you and your wonderful Pokémon!”

Diantha

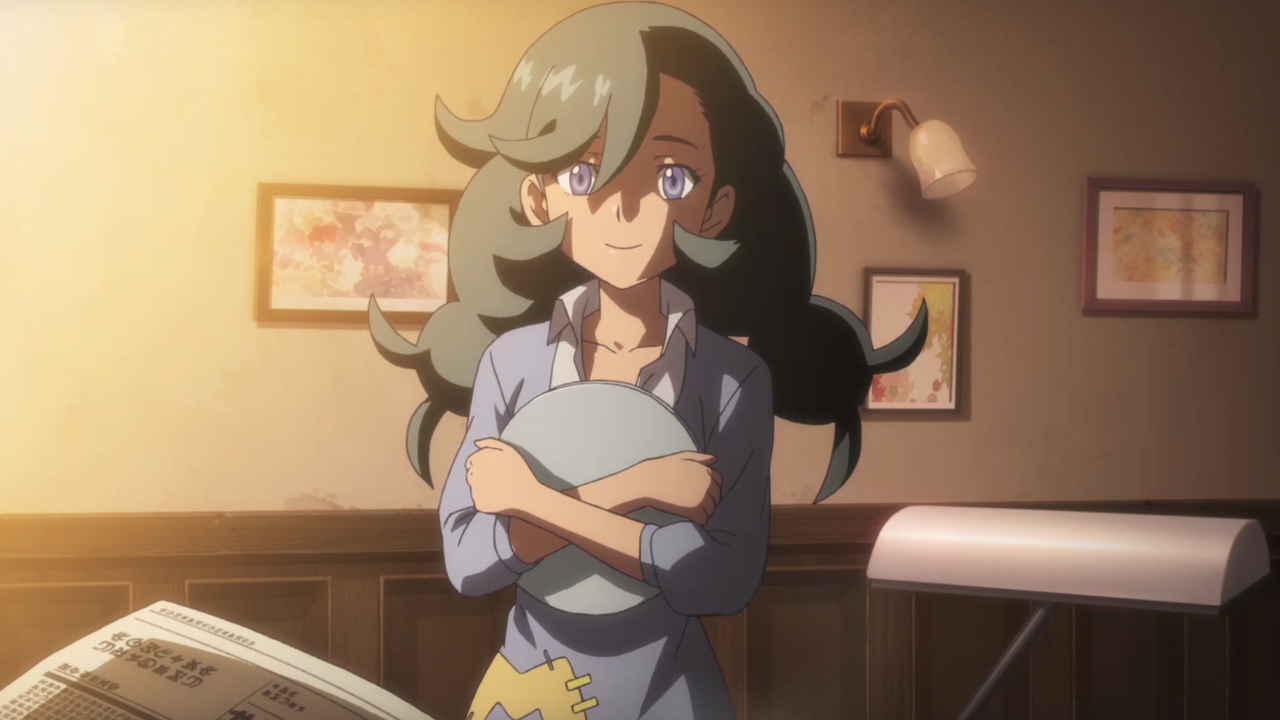

Without any context, Diantha’s dialog seems heavily tied into the idea of “bonds;” discussing Mega Evolution with Sycamore, and claiming she is happy to have met and battled with the player. And yet she lacks the most important aspect of all, which is action: she creates no actual bonds with the player.

The Champion is the final boss in the Pokémon games (with one exception); the entirety of the game—victory over the main villains, encountering the primary legendary of the game, overcoming all obstacles the region has to throw at you—leads up to one moment. The moment the player and the greatest Trainer in the entire region clash. The Champion isn’t just any random Trainer, either: they are someone the player already knows but doesn’t know they are the Champion (again with one exception). It is the bond the player has with this character that makes this fated encounter all the more magnificent—not only are you facing off for the coveted title of Champion, but you are standing against someone who you have a connection with.

In past games, this came in various forms: the first generation sets you against your irritating rival who you couldn’t wait to snatch the title of Champion from. Their sequels have you square against Lance, a Dragon Master who not only assisted you in foiling Team Rocket’s plans, but also spurred on the character development in your rival. Ruby Version & Sapphire Version‘s Champion is your cool mentor who accompanied you occasionally throughout your journey and knew enough of the lore of the region to help you calm the rampaging legendary Pokémon, and in Emerald Version his replacement, Wallace, was still able to assist the player during the climax of the game, even if he hadn’t appeared as frequently as Steven before him. The Champion of the fourth generation games, Cynthia, also assists the player against the nefarious Team Galactic with her strength and knowledge. And in Black Version & White Version, the region’s Champion, Alder, acts as a mentor to the player and Cheren throughout the game, and Trainer Iris, who helps lead the Gym Leaders in an epic clash against Team Plasma near the games’ grand finale, works her way up to the title of Champion two years later in Black Version 2 & White Version 2. In each of these cases, the battle for the title of Champion becomes not just something you do out of obligation—it’s personal now. With this in mind, any Champion with no connection to the player would certainly lack impact, and it’s a shame that this occurred in the games which very clearly want to focus on the concept of “bonds.”

Diantha is only met with twice before your battle in the Radiant Chamber of the Pokémon League. Your first encounter has her discussing beauty with Lysandre, which serves more as an attempt to begin adding depth to Lysandre’s character rather than her’s, and your second has her discussing the vague lore behind Mega Evolution despite Sycamore not having a clear understanding of how it functions at this point. Your very next meeting is when you challenge her, and she even has the gall to point out that she barely recognizes you.

“Oh, I must look like such a fool not to recognize you sooner! You and your Pokémon are the ones who stopped Team Flare for us all!” she proclaims. Despite the player’s goal to become the region’s Champion, there is absolutely no emotional investment in this battle, and even the writers were aware of this when crafting her dialog. Whereas past Champions would occasionally assist the player when up against the games’ villains, Diantha had no role in the plot whatsoever, causing the “big reveal” of the Champion to fall flat when the player realized the Champion is none other than… that lady whose name they can’t remember.

Admittedly, the idea that she is a famous movie star could have been used rather effectively in enhancing her character. Being the Champion is no easy feat, and acting in movies requires a lot of skill, effort, and time as well. When you think about it, Diantha has a lot on her plate and her being Champion while also being a famous actress is rather impressive. However, the player has no knowledge of the kinds of movies she stars in: they are never mentioned throughout the game save for a sentence or two spoken by no-name NPCs. If Diantha had been seen on the set of her latest movie, or if there was a way to see her previous movies (either as a plot point or in a feature similar to Black Version 2 & White Version 2’s Pokéstar Studios), there could have been a better opportunity for a bond of some sort to be formed between her and the player; but as it stands, her lack of involvement contributes to the final battle of the game lacking any emotional investment. It’s an obligation rather than a meaningful fight.

“With strong bonds like that, you shouldn’t have any trouble triggering your Pokémon’s Mega Evolution! As long as Pokémon and Trainers have the kindness to care for each other and give each other courage, the world will be full of smiles!”

Korrina

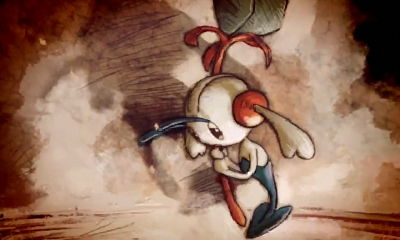

Mega Evolution is a mechanical feature introduced in X & Y. Although it is a battle mechanic at heart, the writers took it upon themselves to incorporate it as a plot point to not only give it some lore, but to also work alongside the games’ theme of “bonds.” Mega Evolution, according to the in-game lore, can be achieved if a Trainer has a Key Stone set into a Mega Ring (or any other accessory onto which a Key Stone can be inlaid), a Pokémon holding the appropriate Mega Stone, and the Trainer and Pokémon share a strong bond.

The first two points are for the sake of the mechanics: in order to achieve Mega Evolution in any battle, the player must have the Key Item to act as an in-game flag that they are allowed access to this feature, and the Pokémon must hold their associated Mega Stone to give it the option to Mega Evolve during battle. The final point is purely for lore purposes, as there is no hidden “bond” stat to determine if the Pokémon can activate Mega Evolution. The player could have the lowest possible points in Friendship (a hidden stat within the game that determines if certain Pokémon can evolve and how much base power Return and Frustration will have) and never have used the all-new Pokémon-Amie feature to raise their Affection stat and they could still Mega Evolve their Pokémon if they have them hold the right Item.

During the game, the player encounters Korrina, one of the eight Gym Leaders of Kalos. She has with her two Lucario, one of whom seems to take a liking to the player. While that’s rather nice, it’s kind of odd at the same time, since you’ve never met this girl nor her two Lucario before. Later, after gaining more insight on the necessary requirements for Mega Evolution, the player must climb the Tower of Mastery and challenge Korrina, who lends you one of her Lucario already equipped with the proper Mega Stone. After the battle you are given the option to take the Lucario.

There are a few things that weaken the overall impact of bonds being a necessary requirement for Mega Evolution: first and foremost is, if a strong bond is so necessary to achieve Mega Evolution, how are you able to use a Lucario you don’t even know and have it Mega Evolve? Right away, all the lore that has been built up surrounding the mechanic is tossed aside in favor of a tutorial battle. In all fairness, there is no easy solution to this. After all, the player can use any Pokémon they choose, so there is no guaranteeing what will be in their party and if they are able to Mega Evolve. But considering that both the well-established Friendship value and newly-introduced Affection value exist within X & Y, it would have served to make the strong bonds “requirement” feel more meaningful if the game had given the player more time to actually spend with this Lucario before the tutorial battle.

This Lucario also ties into another weak spot in the narrative, this time involving Korrina. Korrina is not an interesting character at all; aside from being a Gym Leader, her only purpose is to act as the Mega Evolution Successor and teach the player how to use Mega Evolution. Had the Pokémon chosen for use in the tutorial battle been, for example, Alakazam, the Successor could have just as easily been Olympia. Being the Successor does nothing to add to or change Korrina’s character, leaving her as yet another example of a character who could just as easily been replaced with a nameless NPC. We have to trust that she has strong bonds with her Pokémon because we never see her interact with them outside of her being unable to keep one of her Lucario on its leash when the player is around.

Another aspect that serves to weaken the narrative aspect of strong bonds being required for Mega Evolution is the Pokémon themselves which are able to Mega Evolve. In any game, the player’s first partner Pokémon—what most refer to as their “starter”—is generally considered to be a very close companion to the player throughout their journey. But the starters of X & Y are incapable of achieving Mega Evolution, with that honor instead being given to the starters of the Kanto-based games. While it is completely understandable why the newer Pokémon are not given Mega Evolutions, the fact still remains that the impact of the games’ very own starters, and ultimately all of their new Pokémon, are considerably weakened when Mega Evolutions are given such a prominent plot focus and doesn’t apply to them.

When it comes to the weak aspects of X & Y‘s narrative, the use of Mega Evolution as a plot device is honestly among the least offensive. But very early on, the player will clearly know that strong bonds aren’t actually a requirement, making the sections regarding Mega Evolution feel unnecessary and closer to “padding” rather than meaningful gameplay or narrative segments. The idea of bonds being a requirement to achieve Mega Evolution will also play a role in adding some unnecessary confusion later in the game, which will be discussed in an upcoming section.

“Behind me you’ll find a red button and a blue button. One of them is the button for activating the ultimate weapon. Push one now! Come on! Push one!”

Xerosic

Main-series Pokémon games feature a silent protagonist: after you pick your character’s gender, the player never says a word, except for certain cases where the player is able to pick between “Yes” and “No.” This technique is commonly used in video games as a way to enhance immersion—by not having the main character speak, the player can “fill in” for them by using their own thoughts. This is a used to great success in the Pokémon series, where the player is encouraged to act out their own journey through the region using the main character as an in-game avatar.

There is a slight problem with this in X & Y, however: in these games, the illusion of choice is incorporated. The least offensive example of this is when the player is given the option to pick between receiving a Master Ball or a Big Nugget—regardless of what they choose, both Items are received. This seems harmless enough, but what happens when this is used in a narrative fashion, by a character who should supposedly have no in-game voice?

There are occasions where an NPC will say something, and the player is given two choices to respond with. The issues with these are twofold: first is that the most that changes depending on your choice is no more than one line of dialog. There are even instances where there is absolutely no change in response to the player’s choice whatsoever. If the player’s choice will have no impact, then it is a pointless choice to begin with. The second issue that arises is the dissociation created in regards to the silent protagonist.

In a practical example, the first time you meet with Korrina, as referenced above, her Lucario shows interest in the player, to which Korrina remarks, “Huh. Well, it seems Lucario likes you!” The player is then given two choices, “Thank you!” and “You think so?” Regardless of which is chosen, Korrina continues with, “See, Lucario can read people’s auras.” The first issue is with the options given: what if I, as the player, mentally respond to Korrina’s remark with, “Why does it like me?” or “But we’ve never met before…” My immersion as the silent protagonist is broken in this moment because I have to respond with one of these two options. The next problem comes with Korrina’s response: why bother giving me dialog options if her response doesn’t change? In some instances, there is a very slight change in dialog based on your choice, but nothing substantial. In a case like Korrina’s above, her response isn’t even changed to make her dialog flow better with what was selected; I’d argue that Korrina’s response actually flows better as a reply to either of the two responses I had in my head, rather than the ones presented in-game.

While it makes sense for there to not be major differences based on player choice due to Pokémon games being designed predominantly for single playthroughs, it is still inappropriate for these “dialog sessions” to force a certain voice onto the player. And since these dialog options are most frequently-used during segments with the already insufferable “friend characters,” forcing the player to respond a certain way to them adds to the frustrations players have with them. These segments would have been much better off had they not offered any sort of response options at all, instead allowing the player to respond in their minds with whatever they felt was right to respond with, which is in-line with the silent protagonist model the series follows.

The illusion of choice is most apparent, however, when it comes to Xerosic and the button to activate the ultimate weapon. In the Team Flare HQ, Xerosic gives the player a choice: press a red button or a blue button. One of them activates the ultimate weapon.

The red button activates the ultimate weapon, and the blue one does not. But regardless of which is pressed, Xerosic activates the weapon anyway. This is simply a waste of the player’s time. If the weapon was going to be activated, why bother going through the trouble of having the player decide which button should be pressed? In addition to this, however, another problem arises: they try to take this segment and actually give it relevance a little later. If the player presses the blue button and Xerosic activates the weapon, Lysandre “apologizes” to the player: “Conflicting egos drive this world—things don’t always go the way you want!” This line, as we will discover later, is very telling of Lysandre’s true character, and yet it is only delivered if the player selected the blue button. Players who randomly chose the red button (because there is nothing to convey that the blue button is the “right” choice, unless you make the connection between Yveltal’s red and Xerneas’s blue) never get to hear this line of dialog, despite its importance in conveying Lysandre’s true colors—they don’t even get a separate line to make up for it; the dialog in question is simply cut out.

The red button activates the ultimate weapon, and the blue one does not. But regardless of which is pressed, Xerosic activates the weapon anyway. This is simply a waste of the player’s time. If the weapon was going to be activated, why bother going through the trouble of having the player decide which button should be pressed? In addition to this, however, another problem arises: they try to take this segment and actually give it relevance a little later. If the player presses the blue button and Xerosic activates the weapon, Lysandre “apologizes” to the player: “Conflicting egos drive this world—things don’t always go the way you want!” This line, as we will discover later, is very telling of Lysandre’s true character, and yet it is only delivered if the player selected the blue button. Players who randomly chose the red button (because there is nothing to convey that the blue button is the “right” choice, unless you make the connection between Yveltal’s red and Xerneas’s blue) never get to hear this line of dialog, despite its importance in conveying Lysandre’s true colors—they don’t even get a separate line to make up for it; the dialog in question is simply cut out.

A simple fix could have been to have either Calem or Shauna join the player during this scene and have Xerosic ask them to press a button instead. They could always press the blue button, allowing Lysandre to always deliver his line. Some control would be taken away from the player, but I feel it is a better alternative than having players potentially miss a very important line of dialog. Options like this are already a poor choice when the end result (in this case, the activation of the ultimate weapon) is the same, but even moreso when it causes the player to miss out on something in a game that is primarily designed for a single playthrough.

Lysandre also attempts to add in a theme regarding destiny, or “being chosen,” but this, too, is not utilized to its full potential. Rather, it’s barely utilized at all. It’s mentioned enough times that, if you’re looking for it, you’d believe it has some sort of grander theme across the game, but upon closer inspection is barely sensible. Lysandre describes the player as a “chosen” one, in that they are chosen to receive the Pokédex from Sycamore, they are one of the chosen few who can achieve Mega Evolution, and they are chosen by either Xerneas or Yveltal in the Team Flare HQ. It’s ironic in a way that there is this idea of the player being “chosen” in a game that puts a lot of effort in attempting to portray them as someone who can choose.

Even in other areas, this attempted theme is lost, such as when Lysandre and Diantha converse, in which Lysandre describes her as someone who was “chosen to be a movie star.” There is a little truth in that one does need to be hired (chosen) for the job, but to describe it in such a way removes the agency from the person in question, who undoubtedly worked hard to achieve their goal. Sycamore also describes Lysandre as a “chosen one” at one point, in regards to him being descended from the Kalos royal family. But there is no context given as to what that title does to make him chosen in any way, especially since Sycamore’s other instances of praise towards him are in regards to his achievements and not his ancestry. It’s definitely an interesting point of conflict that the game attempts to give the player a sense of choice, but at the same time goes out of its way to exemplify instances of being chosen, which have nothing to do with the choices they’ve made or achievements they’ve accomplished.

“You played a young girl so wonderfully in your debut on the silver screen. Wouldn’t you rather remain young and beautiful forever and always play such roles?”

Lysandre

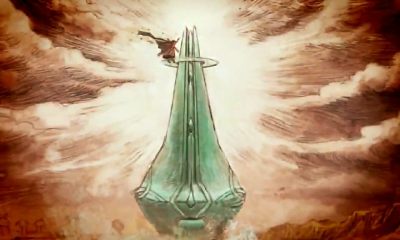

Life versus death: generally, one is viewed more positively than the other. But how does X & Y portray them? A major instance of the portrayal of “life versus death” can be seen through the ultimate weapon. This creation, as the name implies, is a weapon capable of massive destruction. But it is also the same unit that was used to bring AZ’s beloved Floette back from the dead. With the clear ability to both give life and end it, the ultimate weapon is an explicit symbol of the notion of life and death being “two sides on the same coin.” Without life, there cannot be death—without death, there cannot be life.

And yet, once the backstory of AZ and his creation is over, focus returns once again to the weapon as a weapon. Its primary role in the timeline within X & Y is to be utilized as a weapon to wipe out most of life on earth by Team Flare—an awful device, indeed. This portrayal of death is highly negative, and for good and understandable reason. But there is so much focus on this aspect of the weapon that it is all too easy to forget that its original purpose was to give life. This not only weakens its execution as a symbol representing life and death, but makes for a rather jarring wake-up call when, after his defeat in X, Lysandre claims he will use it and Xerneas’s combined power to inflict eternal life upon the player and their friends. He spent the entire game trying to utilize the weapon as a death device and yet it is only in Y where he threatens to use that power against the player; as someone who played X, his final threat felt like it came straight out of left field.

In order to understand exactly what the writers were going for with this, we have to ask: while death is almost constantly portrayed negatively, is life ever shown as bad, too? Upon closer inspection, we find that it actually is—through the depiction of AZ’s immortality.

In order to understand exactly what the writers were going for with this, we have to ask: while death is almost constantly portrayed negatively, is life ever shown as bad, too? Upon closer inspection, we find that it actually is—through the depiction of AZ’s immortality.

Although it will be discussed further in an upcoming section, AZ gained immortality from his ultimate weapon—or should we call it the “ultimate creation?”—in addition to reviving and granting the same status onto his Floette. The Floette left him, causing him immeasurable sorrow. For 3,000 years he traveled, hoping to find his beloved Floette. No one else could take its place—after all, anyone would inevitably die in what seemed like no time at all to him. All he really had was his drive to find his Floette, which had to be spread thinly across over 1,095,000 days.

In a very sublime storytelling segment of X & Y, the player comes to learn of AZ’s suffering. Through it, we are presented with the curse of immortality: the negative aspect of life, life everlasting. And yet, as we will come to discover, AZ’s lack of involvement, coupled with the delicate subtlety with which the subject is handled, makes it easy for the player to forget that it is a very key idea in line with the games’ overall themes. This contributes to the player forgetting the full capabilities of the ultimate weapon, while also making the game feel like it focuses solely on the negativity of death when that likely wasn’t the intention.

The final instance of life versus death in the narrative comes from the first time the player is introduced to Diantha. Lysandre asks her if she wouldn’t prefer to remain young forever, allowing her to continue to play beautiful, youthful characters in her movie roles, to which she replies, “Youth may be beautiful, but it’s not all there is to life. Everything changes.” At first, this seems like a simple enough statement, but it actually poses some complexity. It will come up again later, but for now, we shall discuss it in relation to the theme of life versus death.

Although Diantha does not say it outright, this is actually the game implying that death is a necessity, and it can be embraced as a natural part of life. It’s actually rather clever: Lysandre suggests to Diantha the possibility of staying young forever—a topic frequently brought up alongside life everlasting, eternal youth. But Diantha dismisses it and holds to the belief that aging brings about welcome change. But aging also brings living creatures closer to inevitable passing. The discussion is an effective way to deliver the idea that death is a necessary element of life, and age can bring about change that helps people grow and experience new things. It is subtle enough to likely not be understood by most of the younger players—this general topic can undoubtedly be a tad too heavy-handed for a large portion of the Pokémon series playerbase—but with enough thought, the more mature audience will certainly catch onto it.

But like AZ’s immortality, its subtlety can be easily lost, considering the majority of other narrative elements don’t offer much room for thought. This discussion also occurs very early in the game, making it very easy to forget once the matter of the ultimate weapon starts to manifest. In all, although there was definitely an attempt to portray all the various nuances of the cycle of life and death, a lot of it ends up getting lost in the heavy focus on Team Flare’s utilization of the ultimate weapon for evil.

“Lysandre himself is of royal ancestry… He truly is a chosen one.”

Sycamore

X & Y feature a myriad of characters with little to no impact on the plot. Do you even remember Alexa, Viola’s sister? Did Dexio and Sina’s appearances add anything meaningful to your overall experience? If I named off Aliana, Bryony, Celosia, and Mable, would you be able to match them to the correct Team Flare Scientist? Did Malva’s reveal to be a member of Team Flare affect you in any way? Can you name all the region’s Gym Leaders? I can just barely remember them by their associated Type, and I played through X twice. Although it was a respectable attempt to feature many characters, in the end they are all forgettable and leave no impression on the player due to being one-dimensional in execution.

At the core of X & Y’s plot are three characters featured most prominently, two of whom are at the center of the primary conflict: Lysandre and AZ, with the third being Professor Sycamore. In addition to the primary themes of life, death, and bonds, these three characters feature two additional underlying themes: loss, which ties in with “death” on a more personal level; and obsession. These three characters are the crowning achievement, the primary driving force behind the narrative of X & Y—so where did their execution go wrong? The downfall of these three great men is the most crucial factor leading to the lackluster narrative in these games, and as such they must be discussed separately.

“The man wanted to bring the Pokémon back. No matter what it took.”

AZ

3,000 years in the past, the king of Kalos had his beloved Pokémon forcibly taken from him to fight in an awful war. Some years later, the Pokémon returned to him in its own coffin.

AZ experienced loss through the death of his dear Floette. It resulted in his developing an obsession with bringing it back from death’s embrace; and once he had achieved that, his obsession drove him to the edge, and he used the life-giving machine to end the war by ending the lives of the Pokémon fighting in it.

Pokémon games have touched on mature themes in the past, including death and abuse, but this is the first time such themes are delivered to players so blatantly. A lot of care was taken when developing the central aspects of this plot point, the most obvious of which can be seen on Floette itself: normally Floette have green bodies, while their alternate-color counterparts are a light lavender. AZ’s Floette is blue, calling to mind that it was given new, everlasting life, reminiscent of the blue Xerneas who can “share eternal life.” AZ’s Floette also sports a unique flower, one with a coloration similar to the Destruction Pokémon, Yveltal, and with an appearance similar to the ultimate weapon itself, showing that this Floette metaphorically (and physically) bears the weight of “the lives of many Pokémon [which] were taken to restore its life” on its shoulders.

AZ’s backstory is also beautifully presented, narrated by AZ himself and visually portrayed by aged illustrations, providing an appropriate contrast to the modern appearance of the 3D visuals of the X & Y engine. The music is also appropriately powerful and emotional, and the “flashback” gives enough concrete details on what occurred so the player can clearly ascertain for themselves how AZ felt at the time, and how he continues to feel in the present-day as his search for his wandering Floette continues.

For AZ, his obsession is driven by his loss, which is key in understanding his character. His actions are never justified—even AZ understands what he did was unforgivable, as he describes himself as “a man condemned to wander forever by the light of the weapon,” searching for a way to free himself from “the part of [him] mired in sorrow—the part of [him] that built the ultimate weapon.” But because we understand why he went to such horrible lengths to do what he did, we the players can sympathize with him, and we hope that someday he can be reunited with his Floette.

Aside from this, however, AZ’s involvement in the narrative is painfully minimal. For someone so intent on having Lysandre’s plan of resurfacing the ultimate weapon stopped, he does very little to assist the player in stopping him. It seems rather inappropriate that the character who is so integral to the primary conflict—if it wasn’t for AZ, the ultimate weapon would not exist, after all—is so uninvolved in the story. The first time he is seen in-game, he is still wandering, but ultimately does nothing to advance the story. The next two times, he gives the backstory of himself, Floette, and the ultimate weapon, and implores the player to stop Lysandre. Once Lysandre is stopped, AZ is nowhere to be found until the very end of the story, when he challenges the player in an attempt to understand what it means to be a “Trainer,” and his Floette descends towards him after the battle.

Certainly, the player wants to see AZ and Floette reunited, and the moment is incredibly touching, but something about it almost feels unwarranted. We know he has suffered and searched for thousands of years for Floette, but because we haven’t seen much, if any, of his search for Floette, we’re taking most of what we know from through the grapevine, essentially weakening its impact—in other words, it would have been more effective if players had been shown AZ’s struggle rather than told about it. While the presentation of his backstory was effective, it didn’t do him many favors for his present-day depiction. Because we don’t see him take any action throughout the story, the potential for a more impactful reunion is lost. As it stands, AZ is one of the better-executed characters of X & Y, tackling mature themes with appropriate subtlety. But this subtlety is all too easily drowned beneath the weight of the rest of the games’ ideas that his lack of overall involvement weakens his memorability.

“I can only see one future! One where selfish, foolish humans think about nothing other than themselves and steal more and more from one another… It’s a tragic future!”

Lysandre

In the present, an influential leader and inventor uses the resources at his disposal to any advantage that he can, working to create a future that fits into his definition of “beautiful.” To achieve this, however, he must rid the current world of those who would tarnish it with their greed.

Lysandre himself has never experienced loss, but his beliefs drove him obsessively towards his goal of creating a beautiful world. He would go to any ends to achieve it, including utilizing the ultimate weapon to end the lives of anyone who wasn’t in Team Flare.

Lysandre, whose name is actually not pronounced as “Lysander,” is a clear parallel to AZ. In addition to connecting them through blood—as Lysandre is descended from AZ’s younger brother—they are connected through the ultimate weapon. Although AZ did initially use it to grant eternal life, he ultimately used it to end the lives of many. Lysandre did not intend to bestow eternal life upon anyone, but his goal revolved around powering the weapon to kill all those who were not associated with his Team Flare.

Unlike AZ, however, Lysandre has experienced no loss of his own. His business, his inventions, his lab, and even his café are all successful. We know of no close friends or family who he may have lost. While AZ was a little sympathetic because we felt his pain and understood why he activated the ultimate weapon, Lysandre does not have any sort of motivator for his actions—he experiences no loss to act as a catalyst for working towards his goal.

One may wonder, does Lysandre need to have directly experienced something to trigger his obsession? Maybe his heart lies in the right place. After all, isn’t it natural to want a world where people are kind to each other and there are no wars? While this is certainly true, the issue with this lies in the way that Kalos (and to an extent, the entire Pokémon world) is presented. For all the player knows, there’s only been one war. The only instance the player sees of poverty in Kalos is in regards to Emma, a single girl (who we shall discuss later). And no one is particularly selfish, either: if the player refuses to leave a tip, certain NPCs may appear irritated, but who’s not to say the player is the one being selfish in that instance? Even overpopulation leading to a scarcity of resources is never touched upon—one would almost think the overabundance of available wild Pokémon in the Kalos region could be a hint of this beginning, but it is never mentioned as a plot device, and is likely only meant to give the player a wide variety of Pokémon to catch for their team. The only people who are taking things for themselves, hurting others, and threatening the peace is Team Flare themselves. When Kalos is presented as a region with no dirty underbelly, where everyone is kind and courteous, and poverty is practically nonexistent, Lysandre’s rantings seem almost akin to a conspiracy theory. The player cannot find justification in the extreme measures Lysandre wishes to take due to the circumstances not existing to begin with.

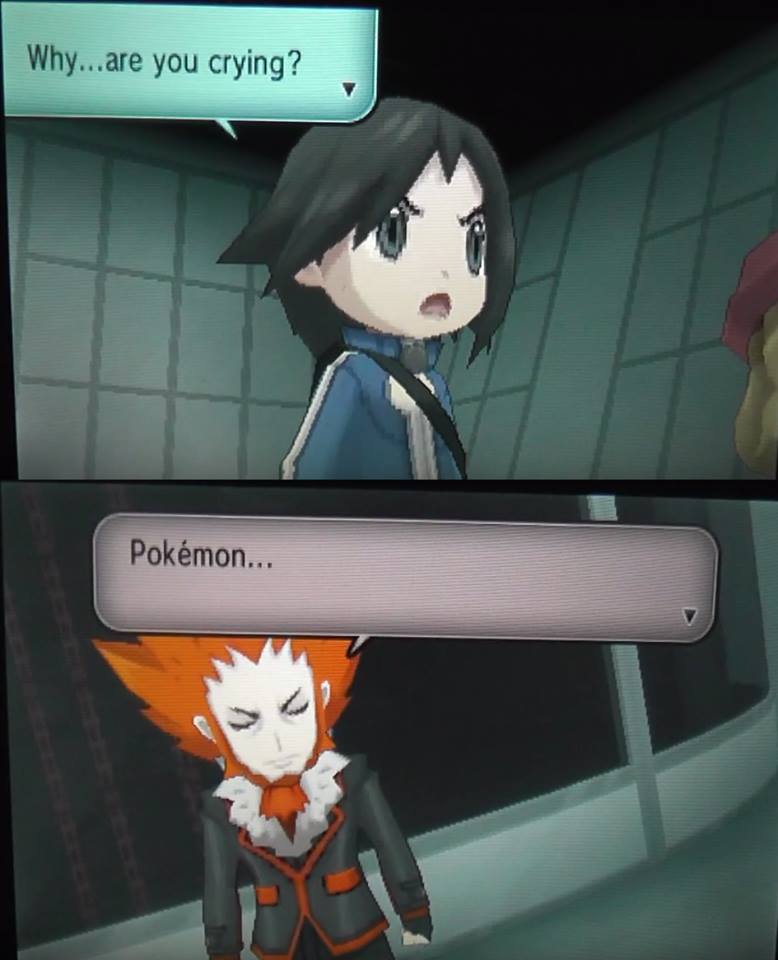

Still, there should be an easy fix to this. Lysandre does not have to be sympathetic. After all, Pokémon games have had villains with little to no justification for their actions, being evil for the sake of being evil, and they were generally received well for their extreme characterizations. And if Lysandre had similarly been portrayed as a man who was too far gone to reason with, perhaps his character would have been more successful. And yet, that is not what the writers had in mind—for within the Team Flare HQ, Lysandre is asked what will become of Pokémon as his plan unfolds. He sheds visible tears and claims that because Pokémon are wonderful and helpful by nature, they must perish to prevent them from being used as tools of war and targets of theft. He understands there is wrong that will come from his plan, but to Lysandre, it is still a necessary sacrifice.

Keep in mind that X & Y were the first Pokémon games in full 3D. Characters have very limited facial expressions and body language is even more scarce, usually just limited to vague hand gestures, and is more apparent before and after a battle when (and if) the opponent is shown in their full-scale model—a model limited to the player, their rival, their friends, Sycamore, and Lysandre. Time and care was taken to include this scene where Lysandre is shown visibly crying over how he will have to bring about the death of Pokémon. To describe it as important is an understatement.

But we must ask, is this scene sensible? We have established that Lysandre’s goals have no motivation behind them. The player cannot sympathize with Lysandre, and yet this scene exists to create sympathy for him. If Lysandre was meant to be sympathetic, he should have had his obsession driven by a reasonable motivation. If Lysandre was not meant to be sympathetic, he should not have had focus drawn to this sympathetic aspect of his character. It is a very impactful scene, which can easily make players believe they should view Lysandre as misguided or with his heart in the right place. But there is no way to overlook that his extremism is completely unwarranted. These are clashing character elements that weaken Lysandre’s character and affect how seriously he is taken by the player. In addition, Lysandre can no longer even be thought of as a foil to AZ because of the attempt to portray him as sympathetic.

While the most blatant disservice done to Lysandre’s character was the conflicting attempt at making a non-sympathetic character sympathetic, there are other weaknesses in his execution, too. We have already gone over Lysandre and Diantha’s discussion regarding the beauty of youth, but in regards to its importance in the themes of life and death. As an early showcase of Lysandre’s character, however, it falls flat. “Isn’t it your duty to be ever beautiful?” he asks. “Everything beautiful should stay that way forever.” It’s easy to grasp the meaning of his words: youth is generally considered to be more physically beautiful than old age. But it is a very shallow mindset. While there is nothing wrong with striving for physical beauty, metaphorical beauty is thought of as more meaningful.

But isn’t Lysandre’s dream of a metaphorically beautiful world? A world without wars or conflicts? And surely, a world ravaged by the might of the ultimate weapon would not be physically beautiful—at least, not right away. Lysandre does indeed seek a metaphorically beautiful world, but one of his earliest instances of dialog implies otherwise. Or is it just as conflicted as his portrayal as simultaneously sympathetic and unsympathetic? In nearly the same breath, he praises how Diantha “dedicates her life to making other people happy,” which is certainly a (metaphorically) beautiful thing.

Another source of conflict comes from his Mega Gyarados. We have already established that the requirement of a “strong bond” to activate Mega Evolution is a plot point that is weakened by the game mechanics itself. As we already know, Lysandre isn’t one we’d call “sympathetic;” but at the same time we do know he cares for Pokémon. Because of these conflicting ideas, it’s impossible to know what Mega Gyarados stands for on his team.

In prior Pokémon titles, there were some cases where mechanics were used as storytelling elements: more specifically, by having certain characters appear with certain Pokémon, the player could infer that the character had experienced some sort of change. Arguably the most well-known example of this would be the player’s rival in the Johto-set games, who goes from being a downright villainous youth to a more understanding one, and showing this through his Golbat’s happiness evolution into Crobat. Using game mechanics to deliver narrative elements can be difficult but truly phenomenal when done right—after all, only video games have access to such narrative delivery. They can be subtle enough to allow for meaningful thought from the player, but is simultaneously seamlessly integrated into the overall experience that comprises a “game.”

There must be some importance to his Mega Gyarados. The way Mega Evolution is handled in X & Y is what confirms this: Mega Evolution is used by very, very few select Trainers across the entirety of the game. Whether the lore behind Mega Evolution was a byproduct of keeping Trainers who use it to a minimum to try and keep the game easier, or if it was very much intended to convey how rare Mega Evolution was to achieve, does not change the fact that it is a rather big deal to encounter a Trainer who is able to utilize this mechanic. Let us, then, go over how Lysandre became able to Mega Evolve his Gyarados.

A quick look at his character model reveals that Lysandre does not wear his Mega Ring—the Item he uses to activate Mega Evolution—in the beginning of the story. He begins the game with no way to achieve Mega Evolution. As the story progresses, Sycamore and the player touch base to go over what they learn about the process. Later, before the final battle against him, he dons the Lysandre Machine and claims that he, “too, shall use the Mega Ring and Mega Stone that you researched during your travels.” After his defeat, it is revealed that Team Flare had been using a machine to spy on Holo Caster transmissions all across the region.

Did anyone realize, within that moment, that this was how Lysandre learned how to utilize Mega Evolution? It wasn’t given enough focus when it was relevant, so it isn’t very clear without afterthought. Once this is established, however, we only reach the conclusion that Lysandre learned about the necessary elements to achieve Mega Evolution: possession of a Key Stone, a Mega Stone, and a strong bond between Trainer and Pokémon. But we don’t know how he came to possess these things—namely, how did he achieve a strong bond with his Gyarados? Is the player supposed to think the Lysandre Machine forces the Mega Evolution, or are we to believe Lysandre naturally has a strong bond with his Pokémon? With the information we are given, there isn’t enough concrete evidence to point in one direction clearly, making any theories regarding this subject mere headcanons at best. Because Lysandre’s ambitions are downright genocidal, it’s not much of a stretch to believe that he forced his Gyarados to Mega Evolve (and thus causing him to snap when Shauna points out that Gyarados “shared its power” with him, when in reality it didn’t). But at the same time, the game attempts to portray Lysandre as sympathetic—at least when it comes to his feelings regarding Pokémon—so it is equally as likely that he didn’t need to force his Gyarados to Mega Evolve (making his breakdown afterwards all the less sensible), although that comes with the added issue of further attempting to make an unforgivable character seem sympathetic.

Lysandre’s character fluctuates between two extremes: on one side, he is a character with unshakable aspirations which cannot be forgiven. On the other, he is a character who, deep, deep down, understands the wrongness of his actions but feels they are necessary in order to make the world a genuinely better place. Just like the line that is very telling of the kind of man he is, which he only delivers if the player makes the correct choice beforehand, conflicting egos forced his character in two separate directions. Because of this, although he is one of the most terrifying villains the Pokémon series has seen yet, it is difficult for players to take him seriously. Even from the beginning Lysandre has been beset with juxtapositions too jarring to be effective, with the Team Flare Grunts’ purposefully goofy demeanor compared to Lysandre’s ruthless and all-too-serious true nature. Half of the cards in Lysandre’s hand were against him, and instead of discarding them away, they were kept and played, contributing to his weakened character, which, had only the right cards been played, could have resulted in one of the most multifaceted and menacing characters of the entire franchise.

“Running around all over Kalos is actually rather tiring, is it not? Oh yeah, I’m the one making you do that, aren’t I? Terribly sorry about that!”

Sycamore

Looking to the future, a professor thinks of a life without the person he most admired, his most esteemed colleague. Someone he had respected so greatly that he could not see through their facade, and was completely taken by surprise when he discovered their true intentions.

Sycamore’s obsession with Lysandre resulted in him being unable to discern Lysandre’s true ambitions. His experience of loss can be seen as either his loss of Lysandre when he announces his plans to annihilate life on this earth, or his loss of Lysandre after the conflict with Team Flare is put to rest. In either scenario, he partially blames himself for Lysandre’s actions, as he felt he hadn’t properly spoken to Lysandre on the topic of setting aside his ego to see things from a different perspective.

Unlike AZ and Lysandre, whose obsessions centered around achieving a goal, Sycamore’s obsession revolved around a person: Lysandre. Although Lysandre comes off as rather suspicious in his slick, black-and-orange suit with his ash-red text box, Sycamore is utterly oblivious to his true personality. All Sycamore can think about is how wonderful Lysandre’s inventions have been in improving the lives of both people and Pokémon. My absolute favorite example of Sycamore’s imperviousness is when he invites the player to the overly-red Lysandre Café for a chat, and proceeds to tell them of Lysandre’s passion and how he donates towards Pokémon research. Not even ten steps away from him, you’ll find an NPC who loudly proclaims Team Flare’s brilliance.

Unlike AZ and Lysandre, whose obsessions centered around achieving a goal, Sycamore’s obsession revolved around a person: Lysandre. Although Lysandre comes off as rather suspicious in his slick, black-and-orange suit with his ash-red text box, Sycamore is utterly oblivious to his true personality. All Sycamore can think about is how wonderful Lysandre’s inventions have been in improving the lives of both people and Pokémon. My absolute favorite example of Sycamore’s imperviousness is when he invites the player to the overly-red Lysandre Café for a chat, and proceeds to tell them of Lysandre’s passion and how he donates towards Pokémon research. Not even ten steps away from him, you’ll find an NPC who loudly proclaims Team Flare’s brilliance.

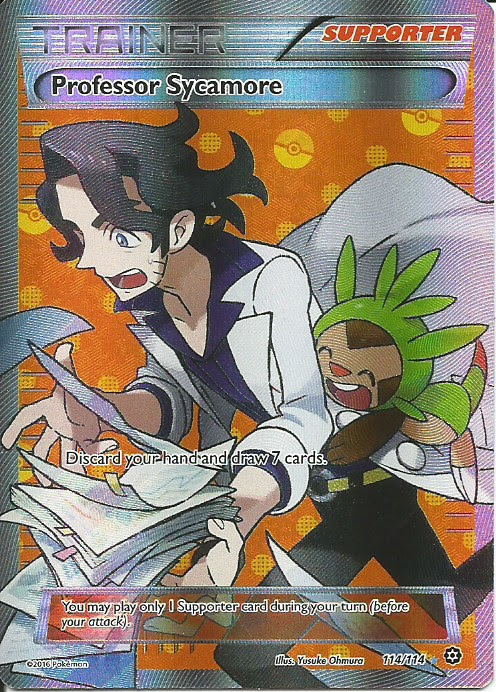

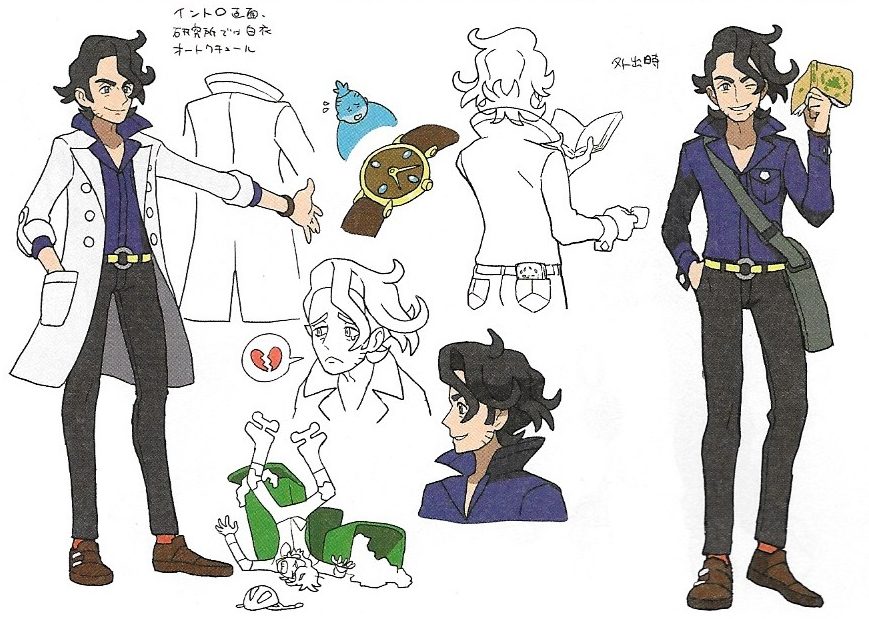

The thing that makes Sycamore different than the other characters of X & Y, however, is that this obvious “flaw” isn’t what ails his character—rather, his unsuspecting nature adds to it. Sycamore is, in layman’s terms, a goof-ball. When he battles the player, he begins by stating he isn’t very good, and ends by shrugging and hanging his head in defeat. You learn from NPCs throughout the region of his other endeavors, including attempting to climb the Tower of Mastery and giving up after scaling not even a single story. The official TCG art you see above shows him dropping his research papers, even though others portray human characters in much more dignified poses, and the official concept art you see below lovingly displays his attempts at roller-skating—which cause him to crash into a trash can. And along with these examples go his naiveté regarding Lysandre’s true colors.

These minor quirks in his character make him the most “human” out of anyone to appear in X & Y. His flaws aren’t grandiose, and they don’t need to be. Sycamore is meant to be presented as a realistic, down-to-earth professor who greatly admires and respects Lysandre the inventor. But then we must ask ourselves… How would such a “real,” such a “human” character, react to discovering that the person he most admires is attempting to terminate almost all life on the planet?

For Sycamore, we are only told, not shown, of his reaction: Dexio graciously lets the player know that “The professor’s feeling pretty down, but he’s using his network of acquaintances to try to stop Team Flare’s plan.” Sycamore himself makes no appearance, nor does he change his dialog when visited in his lab. Like AZ, whose overall impact was weakened by lack of involvement and existing mostly through saying and not acting, Sycamore similarly does not react in a way befitting the character he has been built up to be.

His opportunity to make up for this is presented after the final battle with Lysandre, when Sycamore invites the player to speak face-to-face with him in Couriway Town. Yet it creates its own set of complications. His discussion with the player begins thusly:

“I have to apologize to you about Lysandre… I’m very sorry for the trouble he caused… And I’d also like to thank you! I’m sincerely grateful for what you did for all of the Pokémon and people of this world. And by stopping Team Flare, you also saved Lysandre.”

Nowhere in his discussion with the player does he hint at being affected by the great loss he had experienced—the loss of Lysandre, metaphorically, by discovering his true nature—nor does his body language convey any sort of sadness. He is the same jovial professor we’ve known since the start of the game. Although Lysandre was shown crying over his own actions, Sycamore was not even given dialog to express the sadness that would naturally occur after losing one’s best friend to his own madness. What we are shown instead is stagnation, an utter lack of change or growth from the experiences he underwent, solidifying Sycamore as a professor who is memorable not as a complex character, but as a character who is respected due to his position, but still exudes an impressive amount of ineptitude.

A whole new can of worms is opened when taking into consideration the ultimate fate of Lysandre. The ultimate weapon collapses into the Team Flare HQ as the player and friends make their hasty escape, leaving Lysandre behind. It is purposefully vague, but a very popular belief is that Lysandre perished beneath the weapon he raised. If it was intended for Lysandre to have died, new meaning is given to Sycamore’s line of, “by stopping Team Flare, you also saved Lysandre,” becoming one of the most profound lines delivered in a Pokémon game. But if you were to believe that Lysandre is no longer among the living after the incident in Geosenge Town, it makes Sycamore’s lack of reaction all the more baffling.

Regardless of your stance on Lysandre’s fate, Sycamore’s lack of growth and reaction to what he experienced is a huge waste of potential. As the first professor to be presented as more of a friend to the player than an adult figure who gives you your starter and leaves you on your way, and as the first professor to challenge the player to battle, Sycamore has numerous novelties working in his favor. But in a manner similar to Calem, who is presented as a character who would act and react in an appropriate manner to the occurrences around him but ultimately does not, Sycamore’s lack of reaction is an utter disservice to the character he easily could have been. Instead of being thought of as an involved, complex professor, he will be known as a charming professor with lots of goofy aspects to his character who would rather send out Dexio and Sina to deal with Team Flare instead of himself getting involved when his best friend was found to be their leader. He is certainly a likeable and memorable character, but he is enjoyed for his very surface-level presentation rather than for anything of deeper meaning.

“Mimi and I don’t need a Poké Ball to be friends!”

Emma

After defeating the Champion, and thus completing the “main story” of X & Y, the “post-game” opens up to the player: activities that can be done only after the credits roll. Included in this are a set of “chapters” which serve as a sort of “bonus mini-narrative,” starring a new character, Emma, and returning character Looker. Looker is known by long-time Pokémon fans for his role in instigating narrative depth, from his series introduction in Platinum Version where he gave new insight on the game’s villains, to Black Version & White Version where he similarly appeared after clearing the game, hunting down the remaining villainous sages while simultaneously reinforcing the fact that the main villain was still at large, acting as a catalyst of sorts to lead into the games’ eventual sequels. In the case of X & Y, which we have already gone through at length to see its thoughtful ideas amount to mediocrity, what can Looker provide now that the primary conflict has been quelled?

The truth is, these “Looker Episodes” feature the strongest storytelling in all of X & Y. The very first chapter of this bonus narrative has the player exploring the labyrinthian Lumiose City for tickets Looker has hidden. The method of finding them, coupled with Looker’s quirky dialog, gives players a quick and succinct feel for his character, one that is arguably better than any depictions of him in his previous series appearances. Players with no prior experience of Looker will be caught up with his character within this first chapter, and there are even small details around the Bureau itself that lend themselves in Looker’s favor, including a notebook which is constantly updated throughout this narrative segment, and a photo on his desk, apparently of Looker and “a bluish-purple Pokémon.” Normally, the use of a notebook to convey “behind-the-scenes” actions, such as teaching the upcoming character how to read and write, would be less effective than actually showing the process, but due to the very short length of these chapters, it is easy to overlook that and instead see the journals as a clever way to add more detail to the story.

Once the tickets are collected, Looker names the player his partner, establishing a bond between them. The next chapter begins, and introduces Emma. Her ragged outfit, unkempt hair, streetwise but booksmart-lacking attitude, and claiming she has always been “living in alleys,” are great ways to quickly establish her as homeless without spelling it out for the player. Looker invites her to live in the Bureau as his assistant, not only creating a bond between the player, Looker, Emma, and her friend, Mimi the Espurr, but also show the player Looker’s caring side, again without having anyone blatantly blurt it out.

The third chapter covers a tourist whose Pokémon has been stolen by a local gang. These characters are simple but quite welcome, as the Japanese-speaking tourist adds believability to Lumiose being a popular spot for tourists to visit, and the inclusion of a gang, albeit rather small and tame, hints at other kinds of people living in Lumiose aside from the well-off café-goers, who are the only kinds of people the player sees when experiencing Lumiose at any other point in the game. The tourist arrives in the Looker Bureau and speaks ill of Looker after he leaves to get her some tea, as he misunderstood her plea for help at her Pokémon being stolen. This angers Emma, and when Looker returns and discovers what really ails the woman, Emma suggests not helping her. This upsets Looker, who claims that regardless of what was said about him, people and Pokémon who need help should be helped. At this, he rushes to confront the gang, and it is revealed to the player that Looker’s partner Pokémon—perhaps that bluish-purple one from the photo?—died in a prior mission, and that Looker has no Pokémon with him. This revelation, while likely incredibly disheartening to Looker’s fans, ties in with the games’ overall theme of “loss” while also further showcasing Looker’s personality through action, having him run headlong into a gang situation with no Pokémon at hand.

The player steps in to quell the situation, and Emma appears. These thugs seem to only want to be Emma’s friends and were displeased that she stopped visiting them once she took refuge in the Looker Bureau. This, along with the previous chapter showing Emma surrounded by children from well-off families wanting to play with her, is yet another strong example of showcasing a character through deliverance of details: never once is the player told anything along the lines of, “Emma is so popular, she is friends with everyone.” But we know that she is likeable and really takes advantage of her access to all of Lumiose by seeing that everyone from kids to gang members want to be friends with her. We also see from Emma more character growth in this moment than most characters achieve throughout the primary story of X & Y, because when she approaches the thugs, she tells them to return the stolen Pokémon, and actually apologize to not only Looker, but the rude tourist—who Emma had, not moments ago, suggested not even helping due to her disrespect towards Looker. We also get to see her monologue at the end of this chapter, worrying over Looker’s apparent lack of funds. This spurs her to look for work to help support him. Take this drive to not be a burden on others, and combine it with her background as a homeless, family-less girl, and it’s very easy to want to root for her success.

In her attempt to start working, Emma gets involved in a part-time job that has her roaming Lumiose in a black suit, allowing her to disguise as any random person, and steal peoples’ Pokémon against her will. The true culprit behind this is none other than Team Flare Scientist Xerosic, who is putting Emma into a coma-like state to control her as she steals Pokémon for him to use in his research. In the player’s attempts to save Emma, we come to discover, through his desperate actions and dialog, that Looker has come to see Emma as his own daughter, deepening the bond they share. And in one final twist, Xerosic is shown to feel similarly. In the final confrontation with Xerosic and his controlled Emma, whom he has dubbed “Essentia,” Xerosic admits that Emma was never in any danger of being harmed. He admits to being obsessed with his research, but unlike Lysandre, Xerosic is willing to stop when things go too far, wonderfully developing his character into one who you’re happy is going to be arrested for his crimes, but you can’t quite think of him as the absolute scum of the earth, either. If anything, Emma’s trust in him is quite convincing, as well. Similarly, Looker is willing to invite Xerosic over for one last dinner before his arrest to make Emma happy, further showing, not telling, the player just the kind of person Looker is: one who is willing to set aside his work when appropriate, due to his caring, fatherly nature towards those he is close to.

Bonds are put at the forefront one last time as Xerosic stalls Looker before they both leave Kalos forever, giving the player and Emma one last opportunity to say good-bye to their friend—or in Emma’s case, her new father. Looker bestows his codename upon the player, and gives the Looker Bureau to Emma, and Xerosic gives her the Expansion Suit to allow her to continue to protect Lumiose City, while saying that her bonds with Looker will always tie them together. Although these side quests didn’t last very long, this departure is just as emotional as AZ’s reunion with his Floette, as each character has burrowed their way into the player’s heart in a way the friend characters only wish they could have done. And in line with the detail-driven chapters, although Looker’s notebook is now blank after his departure, his photograph of his Pokémon has been replaced by one of the player, Looker, Emma, Mimi, and Xerosic, all standing side-by-side. Somehow, this photograph—this photograph with Xerosic, who, if you had told me before I had my copy of X in my hands that he would be the Team Flare Scientist I ended up liking the most, I likely would be unable to hold back a chuckle—feels more rewarding than the parade held in the player’s honor at the end of the main game, likely due to the bonds between the characters feeling much more real.

Now, these side quests don’t come without their faults, especially in regards to X & Y as a whole. For one, this attempted depiction of Lumiose City’s “dirty underbelly” comes far too late—most players don’t care about Lysandre’s motives any more once the primary conflict has been resolved. Looker’s lack of money and difficulty getting work adds to the humility of his character, but ultimately serve to make Emma take action; in other words, Emma’s homelessness is still really the only time the player sees any sort of poverty in the games. The gang that was featured was similarly rather tame, only stealing only a Pokémon or two once, then returning them and apologizing in hopes of becoming better friends with Emma. Ultimately, the main conflict from these chapters still originates from Team Flare (or the remnants of it, in this case), solidifying the proof that poverty and crime are not so rampant as to justify Lysandre’s actions.

Another weakness comes about from getting the side quests to activate in the first place. The player must defeat at least one opponent in the Battle Maison, defeat their rival in Kiloude City, speak to Professor Sycamore at the Anistar Sundial, and only then will the player receive the Holo-Caster clip activating the post-game plot when they revisit Lumiose. I have certainly known of many people who never experienced this aspect of X & Y‘s post-game due to how much needs to be accomplished before they even become available to the player.

A more neutral point is the lack of facial expressions and body language. Although Emma shows a gleeful grin at the very end of the story, she barely has any change of facial expression and no real poses. I consider this a neutral point because although characterization certainly would have been improved had there been more dynamism to their appearance, the fact that the story is still successful without them is a testament to how solid the storytelling is.

Even with these minor hiccups, there manages to be more character development in a single chapter of these “Looker Episodes” than in the entirety of the main story of X & Y. In addition to the depiction of character action and growth, small details such as Looker’s ever-changing dialog and notebook entries, enhance the lore and enjoyment of the experience. The primary characters, Looker, Emma, and Xerosic, are presented in a way that makes the player enjoy their company, with heaps of emotional investment even in such a limited timeframe. The post-game side quests are the highlight of X & Y‘s narrative, and while they may not make up for the lackluster primary story, they are an exemplary way to end the games. Had the main story utilized more of what made the “Looker Episodes” great, X & Y certainly would have been held in much higher regards.

“Please don’t make a sad face on my account. No matter where I go, our bonds will never change. You will be my dear friends … always and forever.”

Looker

And that concludes my tour across Kalos. You’ve learned the secrets behind Mega Evolution, gained some new friends (even if sometimes you wish you hadn’t), and looked into the lives of three important people, one who shaped the history of Kalos, one who studies in the present for the better of the future, and one who had hoped to shape its—and the world’s—future in an image he thought was the most beautiful, although that plan thankfully did not make it out of the present. You saw these men for what they are and gained insight on what they could have been.

There’s a good chance you began this tour thinking the same thing I did: X & Y feature lackluster narratives that make it difficult to look upon them as some of the better titles of the Pokémon series. And you’re right. X & Y are plagued with tame characters who experience no growth, along with a primary conflict centered around a villain with senseless motivations.

Yet there’s something important we can all gather from X & Y, and it’s that the writers tried. I understand and agree with the notion that effort does not make up for poor results; but what we can glean from X & Y goes further than that. Coming off the heels of the generation five games, the games which are near-unanimously considered to be the ones with the absolute strongest narrative in any main-series Pokémon game thus far, may have made the disappointing storytelling in X & Y all the more apparent. However, there was still an attempt made to convey a strong message of the dangers of war and obsession. Pokémon games have been progressively getting more and more narratively focused. The fact that there was an effort made—even if that effort fell flat—to continue to focus on narrative, implementing such mature themes including life versus death and underlying themes of loss, shows that there is a shift occurring in the Pokémon series: a shift that indicates a higher priority being placed on meaningful, thought-provoking narratives, and not just as a one-off for generation five.

Because X & Y make you think, at least to some degree. Maybe you couldn’t stand whenever your “friends” showed up—we all have “those friends” that we can’t really stand, anyways. Maybe you cheered when your favorite team member was able to Mega Evolve for the first time. Maybe you viewed Lysandre’s tears falling to the ground and thought to yourself, “There’s no way I can forgive this guy just because he’s shedding a few tears right now.” Maybe you felt bad for Sycamore after Lysandre formally announced his plans with the ulitmate weapon—maybe you thought Sycamore was an idiot for not realizing it sooner. Maybe your eyes got watery when Floette descended from the sky into AZ’s outstretched arms. Maybe you sing along to the ending theme each time you hear it come up on your song playlist. Maybe it makes you feel thankful for all the people you’ve met and friends you’ve made.