A Look Back at Mobile System GB, Pokémon Crystal’s Online Service

Equipped with the Mobile Adapter GB and a copy of Pokémon Crystal, Japanese owners were able to trade with people far away, long before the days of Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection. Find out what it was like back then!

These days, we tend to take our Nintendo 3DS’ wireless capabilities for granted. No matter where you are in the world, you can trade and battle Pokémon as well as meet other users — without needing to be physically close to another player — simply by jumping into Festival Plaza.

But did you know that Japanese owners of Pokémon Crystal had online connectivity as well? Players who owned a Mobile Adapter GB could connect their consoles to their cell phones, allowing their phone to act as a modem to connect their games to Nintendo. As far back as 2001, players with a Mobile Adapter could battle, trade, and use a trade system much like the GTS, all while tethered only to their cell phones. This functionality predated the Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection, which launched November 2005, and it wouldn’t be another year until Pokémon Diamond and Pearl released and once again enabled online functionality on the Pokémon games, this time to a global audience.

But did you know that Japanese owners of Pokémon Crystal had online connectivity as well? Players who owned a Mobile Adapter GB could connect their consoles to their cell phones, allowing their phone to act as a modem to connect their games to Nintendo. As far back as 2001, players with a Mobile Adapter could battle, trade, and use a trade system much like the GTS, all while tethered only to their cell phones. This functionality predated the Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection, which launched November 2005, and it wouldn’t be another year until Pokémon Diamond and Pearl released and once again enabled online functionality on the Pokémon games, this time to a global audience.

As the online functionality never made it outside of Japan, and the service was discontinued a year after it launched, most players have never seen the Mobile Adapter work with Pokémon Crystal. The online functionality has not been replaced in the Virtual Console editions of Pokémon Crystal, either. But thanks to the skilled work of Háčky and YouTubers such as SatoMew, we have even more insight into what they could do. It’s because of these guys that PokéCommunity Daily can present a detailed insight into how Crystal’s online system worked, so without further ado, let’s check out Crystal’s online service!

Table of Contents

- Starting off

- The Mobile menu

- Trading and battling

- Welcome to the Pokémon Communication Center

- Battle Tower on a nationwide scale

- Connecting to Pokémon Stadium

- Why the mobile approach failed

- The future

- Further Reading

Starting off

The Mobile Adapter GB was sold separately from Pokémon Crystal, and initially cost 5,800 yen — 2,000 yen more than the game itself. The Mobile Adapter was sold in multiple variants with multiple colors, each color model specific to a Japanese cell phone carrier. Due to the way the Mobile Adapter was designed, peer-to-peer connections were not supported with other Mobile Adapter models, and thus could not communicate with other players on different carriers.

The KDDI DION Mobile Adapter, which was primarily marketed in press shots of the Mobile Adapter GB, came with several leaflets and a plan registration form, in which users would find a temporary username and password in which they’d need to log into the Mobile System GB. Players would have to mail in the form within 15 days — their account would otherwise expire.

After setting up a Mobile Adapter using the bundled Mobile Trainer cartridge to configure the adapter and complete temporary registration, you could then connect it to your Game Boy Color, switch on Pokémon Crystal, and use it right away. Once the game recognised a configured mobile adapter, upon continuing a game or starting a new one, you would be prompted to fill in your profile. Players were asked to fill in their gender (this replaced the “are you a boy/girl” prompt if you started a new game), city and optionally, their postcode. You would then be able to use mobile functions as early as the moment you’d delivered the Mystery Egg to Professor Elm — from this point, the “Mobile” menu was available, allowing players to change their public profile and manage their contacts. Additionally, the second floor of the Pokémon Centers would be opened up.

The Mobile Adapter GB would connect to the aptly-named Mobile System GB. The Mobile System GB would connect players to the “Mobile Center,” the servers providing Crystal’s online functionality. The adapter could also be used to dial in and connect to other players, referred to as peer-to-peer connections.

The Mobile menu

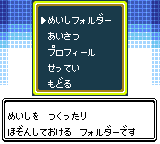

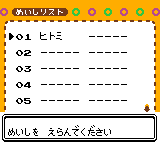

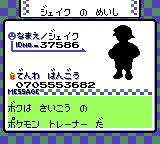

The Mobile menu provided access to a “Card Folder” and various options to change their profile (the city and postcode mentioned above), greeting and connection settings. The Card Folder is a store for contacts and their phone numbers, similar to the Pal Pad friends list in the fourth-generation games — players could add their friends’ mobile numbers to allow the mobile adapter to call them to trade or battle. Alternatively, at the conclusion of a trade or battle with someone who wasn’t already in your contacts, the game offered to exchange these contact cards.

The Mobile menu provided access to a “Card Folder” and various options to change their profile (the city and postcode mentioned above), greeting and connection settings. The Card Folder is a store for contacts and their phone numbers, similar to the Pal Pad friends list in the fourth-generation games — players could add their friends’ mobile numbers to allow the mobile adapter to call them to trade or battle. Alternatively, at the conclusion of a trade or battle with someone who wasn’t already in your contacts, the game offered to exchange these contact cards.

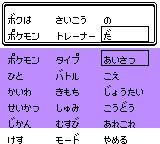

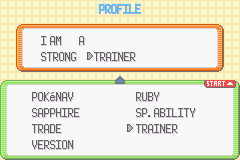

Pokémon Crystal also allowed you to set certain phrases — using the Easy Chat system most people would’ve seen first in Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire. You could create a phrase which would show on your contact card, as well as phrases for when other players encounter you pre-battle, when you’re defeated, or when you win the battle. These were used in the Battle Tower, which worked very differently in the Japanese versions as we’ll touch on later. Players would once again be able to set these phrases in Ruby, Sapphire and Emerald (pictured).

Pokémon Crystal also allowed you to set certain phrases — using the Easy Chat system most people would’ve seen first in Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire. You could create a phrase which would show on your contact card, as well as phrases for when other players encounter you pre-battle, when you’re defeated, or when you win the battle. These were used in the Battle Tower, which worked very differently in the Japanese versions as we’ll touch on later. Players would once again be able to set these phrases in Ruby, Sapphire and Emerald (pictured).

Trading and battling

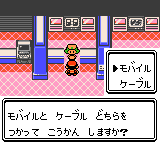

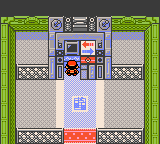

Both the Trade Center and Colosseum on the second floor of any Pokémon Center had two doors in Japanese versions of Crystal. The doors to the left were used for link cable trades or battles, and the doors to the right — accessible once a Mobile Adapter has been connected — were used for peer-to-peer mobile connections. To connect to others in these rooms, you could either enter their phone number manually or pick their card from the Card Folder to dial them, and then begin the trade or battle.

Both the Trade Center and Colosseum on the second floor of any Pokémon Center had two doors in Japanese versions of Crystal. The doors to the left were used for link cable trades or battles, and the doors to the right — accessible once a Mobile Adapter has been connected — were used for peer-to-peer mobile connections. To connect to others in these rooms, you could either enter their phone number manually or pick their card from the Card Folder to dial them, and then begin the trade or battle.

Trades worked similarly to how they did with a regular cable trade — to connect and trade with other players, you’d dial them and be treated to a charming connection sequence with a Pichu running from an orb. You would then be connected and could trade like normal — since it wasn’t happening over a link cable, however, the trade animation had changed accordingly. You can see how a mobile trade works in this video by Háčky:

Battles worked a little differently. The most significant change is that the total amount of time spent battling was limited to ten minutes a day, which meant if you battled another player for five minutes, you’d have five minutes left for another battle. This ten-minute time limit did not apply for those with an “Unlimited Battle Adapter” — although there’s few accounts of whether this was ever actually released. The time limit was likely put in place for each day to minimise excessive call costs for the peer-to-peer connection.

Peer-to-peer mobile battles had two other differences: players were asked to pick from three Pokémon only to participate, also to shorten the battle and minimise call costs. In the event that the mobile connection had cut off, the battle would still continue, with control of the opposing player being given to the game‘s AI.

What’s more, peer-to-peer connections don’t rely on the Mobile System GB, so even once the service had shut down, players with compatible cell phones would still be able to dial other players to trade or battle. However, given the proprietary nature of the connectors, the evolution of mobile networks and the proliferation of iPhones and Android phones, there’s likely very few phones that the Mobile Adapter GB could still connect to in the present day.