Does it Take Two? The Sequels and Why We Have Them

Learn about the main-series sequels and the unique storytelling elements they bring to the table.

In the main series of Pokémon games, most titles are stand-alone; that is, you can pick one up and not need to have played any of the previous games to understand the plot. Each new generation of Pokémon places us in a new location, each with its own conflict and group of characters to help solve it. But this doesn’t apply to all the games–a select few are actually sequels, taking place after other sets of games and referring directly to said games as an important element of their narrative. These sequels, as well as their prequels, have their own unique approach to storytelling due to their semi-dependent nature, and on account of them being an abnormality within the series, they are the focus of much fan discussion, especially in regards to the direction of the series as a whole. This article will take a closer look at the narrative elements of this series’s sequels and their predecessors when compared to the numerous games which did not have any follow-ups.

Which Ones are Sequels?

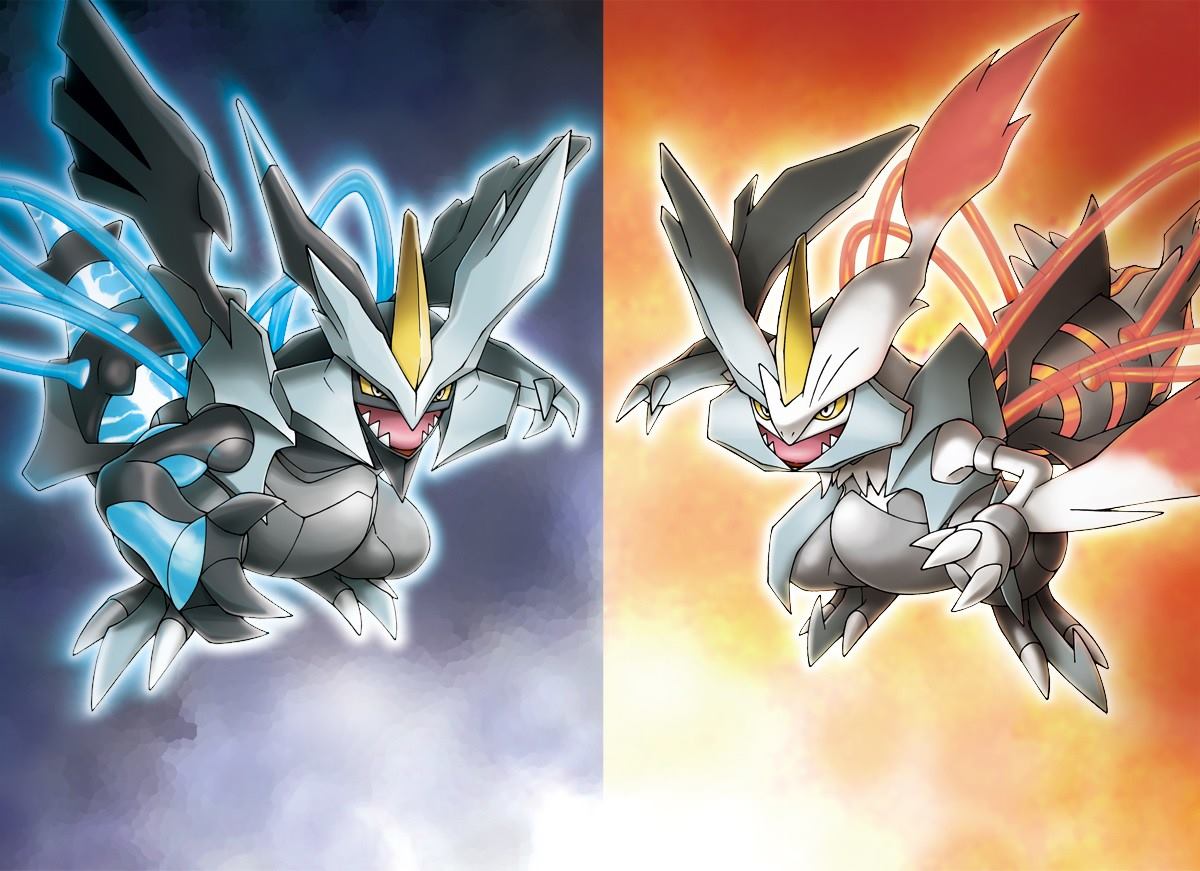

While it may be well-known, it is important to clarify just which Pokémon games are sequels. Black Version 2 & White Version 2 are the most obvious answer–their names are literally the names of their prequels with the number “2” tacked onto the end! A typical naming convention that gets the point across, for sure. But are there others? Actually, there are. Gold, Silver, & Crystal Versions are all sequels to the collective generation one games (fun fact: their tentative titles were “Pocket Monsters 2” and “Pocket Monsters 2: Gold & Silver” in Japan before they dropped the “2”).

The difference here, though, is that the generation two games are indirect sequels, while the sequels of generation five are direct sequels. There’s a little more to this than just one set taking place in a different region than its predecessors, though: the main conflict of generation two, although involving the villainous group of generation one, ultimately centers around a completely different (read: new) cast of characters with entirely separate goals. The generation five sequels, while adding new characters to the forefront of the story, still utilize primarily older characters and a conflict driven by the one established in Black & White Versions.

They’re Not All Metals

When it comes to Pokémon games’ stories, generation one is almost undoubtedly the one most devoid of any. The premise centers around almost cartoonish villains who do bad things because that will earn them the most money. The only character recurring enough to be considered major, your rival, shows no sort of growth as the game progresses. And the primary antagonist, Giovanni, disappears completely after his defeat with no whisper of where he had gone to. The conflict resolved and the matter faded.

It’s this incredible lack of detail, however, that allowed the generation two titles to latch onto these founding games and make use of their plot. Team Rocket’s leader is missing, and some grunts and admins band together to try and get a message to him, wherever he is, that they’re back in black and prepared to make trouble under his guidance once again. It’s a simple, yet effective for the time, conflict for Gold & Silver Versions to use. In addition, the games had a tumultuous development, and with the lack of resources for game developers in general at the time, I can imagine piggybacking off of the plot of generation one would allow them more time to focus on getting the new region, Types, time mechanic (day/night), and Pokémon tidied up.

Compared to generation one, generation two’s games takes a few select non-player characters (NPCs) and emphasizes their action (most notably, Lance) and growth (most notably, your rival). All NPCs from generation one make an appearance, save for Lorelei and Giovanni, but aside from Lance, none of the older characters are featured in the conflict of the games. Even the Pokémon are given a bit more depth: while Mewtwo did have mysterious documents granting it a tragic backstory in generation one, the three legendary birds are just there to be caught and have no associated lore whatsoever. In comparison, not only are the major legendaries of Gold & Silver Versions, who now begin the tradition of gracing the games’ box arts, given their own mythos (a mythos that is focused on through minor sub-plots), but the trio of Entei, Suicune, and Raikou are even bestowed with backstory. And lucky Suicune later went on to be the only minor legendary to feature on a game’s box art and was delegated a new sub-plot all its own in Crystal Version. Also in Crystal Version was a new focus on the Pokémon Unown, and a bit of lore for the Ruins of Alph.

Alternatively, generation one did not add any sort of lore for Articuno, Zapdos, or Moltres despite being granted two “expansions” of sorts (Blue Version and Yellow Version). So while it may be subtle, generation two certainly had a more keen approach to storytelling, regardless of how minor the segments were, than its predecessor.

They’re Not Really Colors

When laid beside generation one, you’ll find a contrast just as stark as black against white–generation five is almost unanimously agreed to be the set of Pokémon games with the strongest narrative. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a useless NPC, and the characters most recurring are the ones who learn and change in response to their dangerous and ethically profound situation. The scenario is sprinkled with meaningful symbolism and offers appropriate levels of player interpretation regarding characters and minor conflicts.

With such a solid story, is there a need for Black & White Versions to even receive sequels? There are two reasons for why Black Version 2 & White Version 2 came into existence: one being for marketing purposes, and the other being for matters relating to Black & White Versions’ story. For the technical reason, it’s almost always a good idea to expand upon an already successful story with popular characters. If a narrative or its cast was not received well, it’s less likely to receive any sort of continuation because, well, who would want to read another story about characters they don’t like? Having such a solid cast placed in an expressive setting makes players want to “keep in touch,” per se–they’d like to see their favorite characters placed into a new scenario and continue their growth after already having experienced some. Since Black & White Versions were written with good characters in mind, it would be easy to assume they would become loved by the general Pokémon fanbase and could be implemented into a sequel for fans to enjoy.

Story-wise, Black & White Versions do a great job at cleaning up after themselves. While certain aspects, such as N and Ghetsis’s true relation, could remain unknown for the purpose of offering player interpretation, all other details are neatly wrapped up and resolved. But the end of Black & White Versions features a rather prominent “sequel hook,” or some sort of narrative element that hints at a possible sequel. For generation five, this hook was Ghetsis’s escape from police custody. The fact that Ghetsis was on the loose was practically drilled into the player in what little post-game content Black & White Versions featured, as Looker requests the players aid in capturing the remaining Seven Sages–and each time the player does this, Looker never fails to remind you that, “Ghetsis notwithstanding,” there are still some Sages left to find. By letting Ghetsis go free, instead of having him repent for his actions (a la Team Magma and Aqua’s Maxie and Archie) or get caught in some sort of alternate underworld-esque universe with no chance of escape (a la Team Galactic’s Cyrus), Black & White Versions set themselves up for a potential sequel, despite seeing the resolution of all their major conflicts.

Black Version 2 & White Version 2 admittedly do not feature as many dynamic characters as their predecessors–characters who appear more frequently, such as Cheren and Bianca, have already done their development and it’s satisfying to see them in their new roles because of it. But new characters who do show growth, such as your rival and Colress, aren’t as many in number when compared to how many returning characters are featured. So while a major focus on plot and character is still undoubtedly present, more so than any other generation of Pokémon games, it is generally accepted that Black & White Versions feature the stronger narrative. That’s not to say that their sequels have a weak narrative–rather, because they are sequels, they have to reach a fine balance of “just enough” in regards to character arcs, as opposed to too much considering their extended cast numbers. However, Black Version 2 & White Version 2 does make up for this with a large amount of gameplay content and all-new modes of play (The Pokémon World Tournament, PokéStar Studios, etc.).

One is the Loneliest Number

Some Pokémon games in particular may seem like they could have been or warranted sequels but ended up with neither. The generation three games cut ties with its predecessors, essentially beginning the trend of generations being stand-alone. It was discussed previously that a potential reason for Gold & Silver Versions to be made into sequels was because it could have made the development process a bit easier on the developers, not having to worry about crafting an all-new, unrelated conflict. With improved resources and a less bumpy development cycle, it was easier to craft an all-new story. Mechanically, this also helped resolve the issue of Kanto and Johto being inaccessible: since the story is completely unrelated, there’s no need to try and cram all those regions into these new games.

Another set of games that did not receive sequels, but fans felt had the potential for, was X & Y. While the fandom in general was fairly split on the possibility of X & Y‘s successors, I feel sequels could not have been possible in a very beneficial manner. The main factor I attribute to this is the continuation of characters’ arcs. The two primary characters of X & Y‘s plot are AZ and Lysandre, in that AZ created the weapon that Lysandre uses, which in turn creates the central conflict of the games. AZ’s development is completely wrapped up, with his Floette returning after he comes to understand the gravity of his actions and what it means to be a Trainer, existing alongside Pokémon. Lysandre’s fate is a little more ambiguous, but it’s an incredibly wide-reaching theory that he perished under the rubble of the ultimate weapon. This causes the biggest hiccup in the idea for X & Y sequels: if Lysandre is dead, there’s no way for him to get the character development fans yearn for. The post-game “Looker Episodes” even tie up loose ends regarding the remainder of Team Flare, leaving nothing to really expand on. Any subsequent game set in Kalos would likely feature a new set of characters in a new conflict, and therefore not really be much of a sequel.

A counterargument would be to just have Lysandre not have died, giving him the opportunity to reappear in the hypothetical “X2 & Y2” games. But after all that’s occurred, would Lysandre truly attempt to rebuild Team Flare from nothing? While he is, in essence, genocidal, he was given a moment of redemption in X & Y‘s climax where he literally (and visually) cries over the Pokémon he would have to kill if his plan were to come to fruition. Whether trying to make Lysandre sympathetic was an appropriate choice or not does not hold much importance in this point. The key takeaway is that he already has some sort of understanding of the atrocities he tries to commit–his own small batch of character development. For Lysandre to try to revive Team Flare would go against this key moment from X & Y; it would paint him as even more of a madman than before. To be fair, this could be a very possible character development for him; however, I feel it isn’t a route Game Freak would take. Ultimately, I believe subsequent Kalos games would work much better as either completely new stories, or at the most, indirect sequels, due to there not being a whole lot to expand upon in terms of unresolved conflicts in X & Y.

Two Can be as Bad as One

The subject of sequels in comparison to the third versions most generations receive usually leads to the question: are sequels inherently better than third versions? And should Game Freak make sequels instead of third versions from here on out? There is certainly an appeal to sequels since their stories are all-new and not just the previous games’ stories slightly altered. But not all stories warrant sequels–in all forms of media we see, all too often, how forced some sequels can be, trying to ride on the coattails of its predecessor without being very impressive and lacking a lot of substance. So while some people may want an alternative to third versions, sequels shouldn’t be that alternative. Not all the time, anyways.

There are definitely times when sequels work. But there’s a fine line regarding what stories can be given (effective) sequels. I firmly believe Game Freak has the right idea in this regard, based on which games they have chosen to give sequels to, and which games they have not. And while sequels are not the norm when it comes to the Pokémon series, the few we have are stand-out titles among the fandom, giving fans a unique blend of new and old characters in new and familiar places with conflicts that hearken back to older games they hold dear. Because sequels aren’t a second chance at making a game right–they’re an all-new look at an old friend.